More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

My relationship with Italian takes place in exile, in a state of separation. Every language belongs to a specific place. It can migrate, it can spread. But usually it’s tied to a geographical territory, a country. Italian belongs mainly to Italy, and I live on another continent, where one does not readily encounter it. I think of Dante, who waited nine years before speaking to Beatrice. I think of Ovid, exiled from Rome to a remote place. To a linguistic outpost, surrounded by alien sounds.

When you live in a country where your own language is considered foreign, you can feel a continuous sense of estrangement. You speak a secret, unknown language, lacking any correspondence to the environment. An absence that creates a distance within you.

Because in the end to learn a language, to feel connected to it, you have to have a dialogue, however childlike, however imperfect.

English anymore. From now on, I pledge to read only in Italian. It seems right, to detach myself from my principal language. I consider it an official renunciation. I’m about to become a linguistic pilgrim to Rome. I believe I have to leave behind something familiar, essential. Suddenly none of my books are useful anymore. They seem like ordinary objects. The anchor of my creative life disappears, the stars that guided me recede. I see before me a new room, empty. Whenever I can, in my study, on the subway, in bed before going to sleep, I immerse myself in Italian. I enter another land,

...more

I read slowly, painstakingly. With difficulty. Every page seems to have a light covering of mist. The obstacles stimulate me. Every new construction seems a marvel. Every unknown word a jewel.

I think of two-faced Janus. Two faces that look at the past and the future at once. The ancient god of the threshold, of beginnings and endings. He represents a moment of transition. He watches over gates, over doors, a god who is only Roman, who protects the city. A remarkable image that I am about to meet everywhere.

When you’re in love, you want to live forever. You want the emotion, the excitement you feel to last. Reading in Italian arouses a similar longing in me. I don’t want to die, because my death would mean the end of my discovery of the language. Because every day there will be a new word to learn. Thus true love can represent eternity.

Every day, when I read, I find new words. Something to underline, then transfer to the notebook. It makes me think of a gardener pulling weeds. I know that my work, just like the gardener’s, is ultimately folly. Something desperate. Almost, I would say, a Sisyphean task. It’s impossible for the gardener to control nature perfectly. In the same way it’s impossible for me, no matter how intense my desire, to know every Italian word. But between the gardener and me there is a fundamental difference. The gardener doesn’t want the weeds. They are to be pulled up, thrown away. I, on the other hand,

...more

When I discover a different way to express something, I feel a kind of ecstasy. Unknown words present a dizzying yet fertile abyss. An abyss containing every...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I’m constantly hunting for words. I would describe the process like this: every day I go into the woods carrying a basket. I find words all around: on the trees, in the bushes, on the ground (in reality: on the street, during conversations, while I read). I gather as many as possible. But it’s never enough; I have an insatiable appetite. I gather words that seem obscure (sciagura, spigliatezza: disaster, casualness) and ones that I can easily understand but would like to know better (inviperito, stralunato: incensed, out of one’s wits). I gather beautiful words that have no exact equivalents

...more

I feel a bond with every word I pick up. I feel affection, along with a sense of responsibility. When I can’t remember words, I fear I’ve abandoned them.

I review the words in order to learn them, memorize them. I think about them while I’m talking to someone. I know they’re there, written by hand in the notebook. If I were a genius, I would remember everything, and would be able to speak much more precisely, fluently. But when I need them the words are elusive, ungraspable. They exist on the page but don’t enter my brain, so they don’t come out of my mouth. They remain stuck, useless, in the notebook. I am aware only of the fact that I’ve recorded them.

The notebook contains all my enthusiasm for the language. All the effort. A space where I can wander, learn, forget, fail. Where I can hope.

During this period when everything confuses me, everything unsettles me, I change the language I write in. I begin to relate, in the most exacting way, everything that is testing me. I write in a terrible, embarrassing Italian, full of mistakes. Without correcting, without a dictionary, by instinct alone. I grope my way, like a child, like a semiliterate. I am ashamed of writing like this. I don’t understand this mysterious impulse, which emerges out of nowhere. I can’t stop. It’s as if I were writing with my left hand, my weak hand, the one I’m not supposed to write with. It seems a

...more

The diary provides me with the discipline, the habit of writing in Italian. But writing only a diary is the equivalent of shutting myself in the house, talking to myself. What I express there remains a private, interior narration. At a certain point, in spite of the risk, I want to go out.

Before I became a writer, I lacked a clear, precise identity. It was through writing that I was able to feel fulfilled. But when I write in Italian I don’t feel that. What does it mean, for a writer, to write without her own authority? Can I call myself an author, if I don’t feel authoritative? How is it possible that when I write in Italian I feel both freer and confined, constricted? Maybe because in Italian I have the freedom to be imperfect. Why does this imperfect, spare new voice attract me? Why does poverty satisfy me? What does it mean to give up a palace to live practically on the

...more

I know that one should have a thorough knowledge of the language one writes in. I know that I lack true mastery. I know that my writing in Italian is something premature, reckless, always approximate. I’d like to apologize. I’d like to explain the source of this impulse of mine.

Why do I write? To investigate the mystery of existence. To tolerate myself. To get closer to everything that is outside of me.

What does a word mean? And a life? In the end, it seems to me, the same thing. Just as a word can have many dimensions, many nuances, great complexity, so, too, can a person, a life. Language is the mirror, the principal metaphor. Because ultimately the meaning of a word, like that of a person, is boundless, ineffable.

If everything were possible, what would be the meaning, the point of life?

Why, as an adult, as a writer, am I interested in this new relationship with imperfection? What does it offer me? I would say a stunning clarity, a more profound self-awareness. Imperfection inspires invention, imagination, creativity. It stimulates. The more I feel imperfect, the more I feel alive.

I’ve been writing since I was a child in order to forget my imperfections, in order to hide in the background of life. In a certain sense writing is an extended homage to imperfection. A book, like a person, remains imperfect, incomplete, during its entire creation. At the end of the gestation the person is born, then grows, but I consider a book alive only during the writing. Afterward, at least for me, it dies.

I think that translating is the most profound, most intimate way of reading. A translation is a wonderful, dynamic encounter between two languages, two texts, two writers. It entails a doubling, a renewal. I used to love translating from Latin, from ancient Greek, from Bengali. It was a way of getting close to different languages, of feeling connected to writers very distant from me in space and time.

Translating myself, from a language in which I am still a novice, isn’t the same thing. I’ve struggled to complete the text in Italian, and I feel I’ve just arrived, tired but thrilled. I want to stop, orient myself. The reentry is too soon, it hurts. It seems like a defeat, a regression. It seems destructive rather than creative, almost a suicide.

In this period of silence, of linguistic isolation, only a book can reassure me. Books are the best means—private, discreet, reliable—of overcoming reality.

Those who don’t belong to any specific place can’t, in fact, return anywhere. The concepts of exile and return imply a point of origin, a homeland. Without a homeland and without a true mother tongue, I wander the world, even at my desk. In the end I realize that it wasn’t a true exile: far from it. I am exiled even from the definition of exile.

“A new language is almost a new life, grammar and syntax recast you, you slip into another logic and another sensibility.”

I was asked, during an interview, what my favorite book was. I was in London, on a stage with five other writers. It’s a question that I usually find annoying; no book has been definitive for me, so I never know how to answer. This time, though, I was able to respond without any hesitation that my favorite book was the Metamorphoses of Ovid. It’s a majestic work, a poem that concerns everything, that reflects everything. I read it for the first time twenty-five years ago, in Latin, as a university student in the United States. It was an unforgettable encounter, maybe the most satisfying

...more

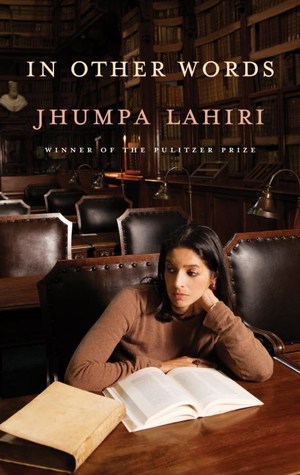

I conceived and wrote this book in a library in the ghetto in Rome. When I came to the city for the first time, more than ten years ago, it was the first neighborhood I discovered. It remains my favorite. I’ll never forget the emotion of seeing the Portico di Ottavia, a short distance from the apartment we had rented for a week. It made such an impression that after returning to New York I wrote, in English, a story set in the ghetto, in which I described the ruins of the portico: “its chewed-up columns girded with scaffolding, its massive pediment with significant chunks missing.” At the

...more

Scaffolding is not considered beautiful. It usually represents a kind of blight. It interferes, it spoils the look of something. Ideally it shouldn’t be there. If I have to walk under scaffolding, I prefer to cross the street. I’m always afraid it’s going to collapse. In the case of the Portico di Ottavia, however, I make an exception. I’ve never seen the portico without scaffolding, so I now consider it permanent, natural. Although it’s an obstruction, the scaffolding adds an element of emotion to the ruin. It seems a miracle to see the columns, the pediment, restored and dedicated in the

...more