More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

you can’t float without the possibility of drowning, of sinking. To know a new language, to immerse yourself, you have to leave the shore. Without a life vest. Without depending on solid ground.

This book allows me to read other books, to open the door of a new language.

In a sense I’m used to a kind of linguistic exile. My mother tongue, Bengali, is foreign in America. When you live in a country where your own language is considered foreign, you can feel a continuous sense of estrangement. You speak a secret, unknown language, lacking any correspondence to the environment. An absence that creates a distance within you.

The language still seems like a locked gate. I’m on the threshold, I can see inside, but the gate won’t open.

Marco and Claudia give me the key. When I mention that I’ve studied some Italian, and that I would like to improve it, they stop speaking to me in English. They switch to their language, although I’m able to respond only in a very simple way. In spite of all my mistakes, in spite of my not completely understanding what they say. In spite of the fact that they speak English much better than I speak Italian.

I renounce expertise to challenge myself. I trade certainty for uncertainty.

Reading in another language implies a perpetual state of growth, of possibility.

Everything has to be learned from zero.

I write my diary in Italian. I do it almost automatically, spontaneously. I do it because when I take the pen in my hand, I no longer hear English in my brain. During this period when everything confuses me, everything unsettles me, I change the language I write in. I begin to relate, in the most exacting way, everything that is testing me.

I write in a terrible, embarrassing Italian, full of mistakes. Without correcting, without a dictionary, by instinct alone. I grope my way, like a child, like a semiliterate. I am ashamed of writing like this. I don’t understand this mysterious impulse, which emerges out of nowhere. I can’t stop.

I don’t recognize the person who is writing in this diary, in this new, approximate language.

precise, I am not at the starting point: rather, I’m in another dimension, where I have no references, no armor. Where I’ve never felt so stupid.

A conversation involves a sort of collaboration and, often, an act of forgiveness.

At the same time she felt a tremendous, consuming uncertainty that canceled out everything, that left her with nothing.

When I give up English, I give up my authority. I’m shaky rather than secure. I’m weak.

the need to write always comes from desperation, along with hope.

Ever since I was a child, I’ve belonged only to my words.

What does a word mean? And a life? In the end, it seems to me, the same thing. Just as a word can have many dimensions, many nuances, great complexity, so, too, can a person, a life. Language is the mirror, the principal metaphor. Because ultimately the meaning of a word, like that of a person, is boundless, ineffable.

current. I live in an era in which almost anything seems possible, in which no one wants to accept any limits. We

A foreign language can signify a total separation. It

To write in a new language, to penetrate its heart, no technology helps. You can’t accelerate the process, you can’t abbreviate it. The pace is slow, hesitant, there are no shortcuts.

In that sense the metaphor of the small lake that I wanted to cross, with which I began this series of reflections, is wrong. Because in fact a language isn’t a small lake but an ocean. A tremendous, mysterious element, a force of nature that I have to bow before.

As a girl in America, I tried to speak Bengali perfectly, without a foreign accent, to satisfy my parents, and above all to feel that I was completely their daughter. But it was impossible. On the other hand, I wanted to be considered an American, yet, despite the fact that I speak English perfectly, that was impossible, too.

When I write in Italian, I think in Italian; to translate into English, I have to wake up another part of my brain. I don’t like the sensation at all. I feel alienated.

translating is the most profound, most intimate way of reading.

A foreign language is a delicate, finicky muscle. If you don’t use it, it gets weak.

In America, when I was young, my parents always seemed to be in mourning for something. Now I understand: it must have been the language.

They looked forward to the mail. They couldn’t wait for a letter to arrive from Calcutta, written in Bengali. They read it a hundred times, they saved it. Those letters evoked their language and conjured a life that had disappeared. When the language one identifies with is far away, one does everything possible to keep it alive.

Now I feel a double crisis. On the one hand I’m aware of the ocean, in every sense, between me and Italian. On the other, of the separation between me and English. I’d already noticed it in Italy, translating myself. But I think that emotional distance is always more pronounced, more piercing, when, in spite of proximity, there remains an abyss.

In this period of silence, of linguistic isolation, only a book can reassure me. Books are the best means—private, discreet, reliable—of overcoming reality.

Those who don’t belong to any specific place can’t, in fact, return anywhere.

Here is the border that I will never manage to cross. The wall that will remain forever between me and Italian, no matter how well I learn it. My physical appearance.

They don’t understand me because they don’t want to understand me; they don’t understand me because they don’t want to listen to me, accept me. That’s how the wall works.

In America, although I speak English like a native, although I’m considered an American writer, I meet the same wall but for different reasons. Every so often, because of my name, and my appearance, someone asks me why I chose to write in English rather than in my native language. Those who meet me for the first time—when they see me, then learn my name, then hear the way I speak English—ask me where I’m from. I have to justify the language I speak in, even though I know it perfectly. If I don’t speak, even many Americans think I’m a foreigner.

can’t avoid the wall even in India, in Calcutta, in the city of my so-called mother tongue. There, apart from my relatives who have known me forever, almost everyone thinks that, because I was born and grew up outside India, I speak only English, or that I scarcely understand Bengali. In spite of my appearance and my Indian name, they speak to me in English. When I answer in Bengali, they express the same surprise as certain Italians, certain Americans. No one, anywhere, assumes that I speak the languages that are a part of me.

I wonder if perhaps the wall is me.

I just wanted to go home, to the language in which I was known, and loved.

couldn’t identify with either. One was always concealed behind the other, but never completely,

realized that I had to speak both languages extremely well: the one to please my parents, the other to survive in America.

None of my teachers, none of my friends were ever curious about the fact that I spoke another language. They attached no importance to it, didn’t ask about it. It didn’t interest them, as if that part of me, that capacity, weren’t there.

I was ashamed of speaking Bengali and at the same time I was ashamed of feeling ashamed.

Even though the language was imposed on me, it has given me a clear, correct voice, forever.

reading in a foreign language is the most intimate way of reading.

Becoming or even resembling an American would have meant total defeat.

He belongs now to the daily rhythm of another country, where the sky is already blue, where he no longer is.

Writing in another language represents an act of demolition, a new beginning.

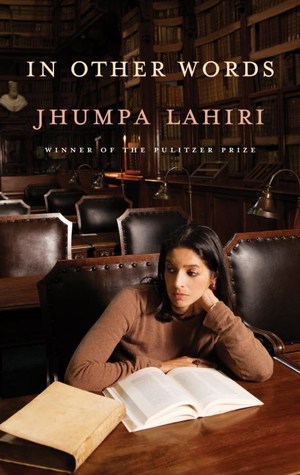

It’s a travel book, more interior, I would say, than geographic.

One writes with the pen, but in the end, to create the right form, one has to use, like Matisse, a good pair of scissors.

once you’ve left, you’re gone forever.