More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

That is his temperament. His temperament is not going to change, he is too old for that. His temperament is fixed, set. The skull, followed by the temperament: the two hardest parts of the body.

Follow your temperament. It is not a philosophy, he would not dignify it with that name. It is a rule, like the Rule of St Benedict.

It surprises him that ninety minutes a week of a woman’s company are enough to make him happy, who used to think he needed a wife, a home, a marriage. His needs turn out to be quite light, after all, light and fleeting, like those of a butterfly.

He ought to give up, retire from the game. At what age, he wonders, did Origen castrate himself? Not the most graceful of solutions, but then ageing is not a graceful business. A clearing of the decks, at least, so that one can turn one’s mind to the proper business of the old: preparing to die.

‘Why? Because a woman’s beauty does not belong to her alone. It is part of the bounty she brings into the world. She has a duty to share it.’

She does not own herself. Beauty does not own itself.

‘From fairest creatures we desire increase,’ he says, ‘that thereby beauty’s rose might never die.’ Not a good move.

She does not own herself; perhaps he does not own himself either.

(unbidden the word letching comes to him). Yet the old men whose company he seems to be on the point of joining, the tramps and drifters with their stained raincoats and cracked false teeth and hairy earholes – all of them were once upon a time children of God, with straight limbs and clear eyes. Can they be blamed for clinging to the last to their place at the sweet banquet of the senses?

Quietly he gets up, follows the

Not rape, not quite that, but undesired nevertheless, undesired to the core. As though she had decided to go slack, die within herself for the duration, like a rabbit when the jaws of the fox close on its neck. So that everything done to her might be done, as it were, far away.

He has long ceased to be surprised at the range of ignorance of his students. Post-Christian, posthistorical, postliterate, they might as well have been hatched from eggs yesterday.

She stares back at him in puzzlement, even shock. You have cut me off from everyone, she seems to want to say. You have made me bear your secret. I am no longer just a student. How can you speak to me like this?

‘YOUR DAYS ARE OVER, CASANOVA.’

Perhaps it is the right of the young to be protected from the sight of their elders in the throes of passion. That is what whores are for, after all: to put up with the ecstasies of the unlovely.

‘I was not myself. I was no longer a fifty-year-old divorcé at a loose end. I became a servant of Eros.’ ‘Is this a defence you are offering us? Ungovernable impulse?’ ‘It is not a defence. You want a confession, I give you a confession. As for the impulse, it was far from ungovernable. I have denied similar impulses many times in the past, I am ashamed to say.’

nothing so distasteful to a child as the workings of a parent’s body.

I was no great shakes as a teacher. I was having less and less rapport, I found, with my students. What I had to say they didn’t care to hear. So perhaps I won’t miss it. Perhaps I’ll enjoy my release.’

road. A cool winter’s day, the sun already dipping over red hills dotted with sparse, bleached grass. Poor land, poor soil, he thinks. Exhausted. Good only for goats. Does Lucy really intend to spend her life here? He hopes it is only a phase. A group of children pass him on their way home from school. He greets them; they greet him back. Country ways. Already Cape Town is receding into the past. Without warning a memory of the girl comes back: of her neat little

It must go on all the time. It certainly went on when I was a student. If they prosecuted every case the profession would be decimated.’

animal-welfare people are a bit like Christians of a certain kind. Everyone is so cheerful and well-intentioned that after a while you itch to go off and do some raping and pillaging. Or to kick a cat.’ He is surprised by his outburst. He is not in a bad temper, not in the least.

You don’t approve of friends like Bev and Bill Shaw because they are not going to lead me to a higher life.’ ‘That’s not true, Lucy.’ ‘But it is true. They are not going to lead me to a higher life, and the reason is, there is no higher life. This is the only life there is. Which we share with animals. That’s the example that people like Bev try to set. That’s the example I try to follow. To share some of our human privilege with the beasts. I don’t want to come back in another existence as a dog or a pig and have to live as dogs or pigs live under us.’

‘I’m dubious, Lucy. It sounds suspiciously like community service. It sounds like someone trying to make reparation for past misdeeds.’ ‘As to your motives, David, I can assure you, the animals at the clinic won’t query them. They won’t ask and they won’t care.’

Bev Shaw, not a veterinarian but a priestess, full of New Age mumbo jumbo, trying, absurdly, to lighten the load of Africa’s suffering beasts.

‘My case rests on the rights of desire,’ he says. ‘On the god who makes even the small birds quiver.’

the poor dog had begun to hate its own nature. It no longer needed to be beaten. It was ready to punish itself. At that point it would have been better to shoot it.’ ‘Or to have it fixed.’ ‘Perhaps. But at the deepest level I think it might have preferred being shot. It might have preferred that to the options it was offered: on the one hand, to deny its nature, on the other, to spend the rest of its days padding about the living-room, sighing and sniffing the cat and getting portly.’ ‘Have you always felt this way, David?’ ‘No, not always. Sometimes I have felt just the opposite. That desire

...more

‘My child, my child!’ he says, holding out his arms to her. When she does not come, he puts aside his blanket, stands up, and takes her in his arms. In his embrace she is stiff as a pole, yielding nothing.

But he cannot fail to notice that for the second time in a day she has spoken to him as if to a child – a child or an old man.

Sitting up in her borrowed nightdress, she confronts him, neck stiff, eyes glittering. Not her father’s little girl, not any longer.

For the first time he has a taste of what it will be like to be an old man, tired to the bone, without hopes, without desires, indifferent to the future. Slumped on a plastic chair amid the stench of chicken feathers and rotting apples, he feels his interest in the world draining from him drop by drop.

But the truth, he knows, is otherwise. His pleasure in living has been snuffed out. Like a leaf on a stream, like a puffball on a breeze, he has begun to float toward his end. He sees it quite clearly, and it fills him with (the word will not go away) despair.

as far as I am concerned, what happened to me is a purely private matter. In another time, in another place it might be held to be a public matter. But in this place, at this time, it is not. It is my business, mine alone.’ ‘This place being what?’ ‘This place being South Africa.’

A peasant, a paysan, a man of the country. A plotter and a schemer and no doubt a liar too, like peasants everywhere. Honest toil and honest cunning.

‘Anything to do with his slaughter-sheep?’ ‘Yes. No. I haven’t changed my ideas, if that is what you mean. I still don’t believe that animals have properly individual lives. Which among them get to live, which get to die, is not, as far as I am concerned, worth agonizing over. Nevertheless . . .’ ‘Nevertheless?’ ‘Nevertheless, in this case I am disturbed. I can’t say why.’

that is old fashion. Clothes, nice things, it is all the same: pay, pay, pay.’ He repeats the finger-rubbing. ‘No, a boy is better.

Curious that a man as selfish as he should be offering himself to the service of dead dogs. There must be other, more productive ways of giving oneself to the world, or to an idea of the world. One could for instance work longer hours at the clinic.

His thoughts go to Emma Bovary strutting before the mirror after her first big afternoon. I have a lover! I have a lover! sings Emma to herself. Well, let poor Bev Shaw go home and do some singing too. And let him stop calling her poor Bev Shaw. If she is poor, he is bankrupt.

‘It was so personal,’ she says. ‘It was done with such personal hatred. That was what stunned me more than anything. The rest was . . . expected. But why did they hate me so? I had never set eyes on them.’ He waits for more, but there is no more, for the moment. ‘It was history speaking through them,’ he offers at last. ‘A history of wrong. Think of it that way, if it helps. It may have seemed personal, but it wasn’t. It came down from the ancestors.’

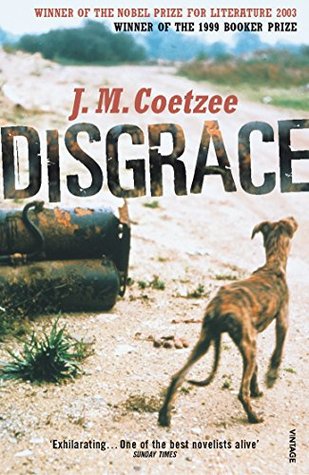

It is not a punishment I have refused. I do not murmur against it. On the contrary, I am living it out from day to day, trying to accept disgrace as my state of being.

He gets to his feet, a little more creakily than

As for Byron, he is full of doubts, though too prudent to voice them. Their early ecstasies will, he suspects, never be repeated. His life is becalmed; obscurely he has begun to long for a quiet retirement; failing that, for apotheosis, for death.

‘Lucy and I still get on well,’ he replies. ‘But not well enough to live together.’ ‘The story of your life.’ ‘Yes.’ There is silence while they contemplate, from their respective angles, the story of his life.

‘Because I couldn’t face one of your eruptions. David, I can’t run my life according to whether or not you like what I do. Not any more. You behave as if everything I do is part of the story of your life. You are the main character, I am a minor character who doesn’t make an appearance until halfway through.

‘Yes, I am giving him up.’