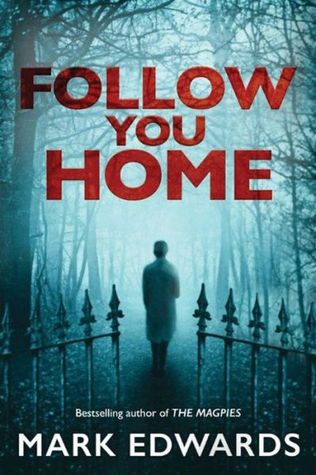

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

PTSD is where your brain remains in psychological shock, unable to shake off or move on from what happened to you.’

‘Actually, I don’t think it was that coherent, if there were fully formed words in my head. It was more like screaming. Like white noise. Also, Laura said afterwards that she remembered screaming as we ran out of the forest, but I don’t remember that. In my memory, she didn’t make a sound.’

It felt like a ghost town.’

‘Just before we walked off, she reached up and touched Laura’s face, whispered something in Romanian. I thought Laura was going to start screaming and I had to pull her away.’ I left out a detail. The woman had also touched Laura’s belly, laying the flat of her hand on my girlfriend’s stomach and nodding to herself. Laura had jerked away like the woman had stabbed her.

‘Wait here,’ he said, placing his hands on his thighs and pushing himself to his feet. Before he left the room he turned back and said, ‘You are sure . . . no one knows you are here?’ ‘No. I’m sure.’

‘There’s something not right here,’ I said. ‘Why does he keep asking if anyone knows we’re here? I don’t like it.’ I went to the doorway and looked out. There was no one in sight and I couldn’t hear either of the police officers any more. ‘It’s clear. Let’s go.’

‘Polaroids,’ I repeated. Flash. A crouching man, a glint of metal. Flash. Numbers scrawled in ink. 13.8.13. Flash. Flash. Flash.

I reached the second floor and saw that my door had splintered around the lock. It had been kicked in. Tentatively, I pushed the door open.

My laptop, which had been charging on the desk, was gone.

‘But I think Laura’s starting to imagine things. Really weird things.’

‘Anyway, that’s when she spoke. She said, “Out there. In the trees.” And she pointed towards the garden, down where the shed is.’

She seemed a little spaced-out, distracted. I noticed that she was wearing her poppy hair scrunchie, which I thought of as her signature item. The number of times she’d lost it and we’d spent half an hour crawling around the flat searching for it.

Why had we reacted to the aftermath of Romania in such different ways? One of us wanting to cling, the other needing to get away. A mutually impossible situation. Deep down I knew the answer. And I didn’t know what to do about it.

When I emerged on the other side, he was ascending the steps onto the main road. As if he’d hailed it, a bus glided to a stop and he jumped aboard. I ran as fast as I could, but as I reached the bus stop, panting and sweating, the bus set off. There was no sign of the man through the window.

I was certain the man under the bridge had been there specifically to watch Laura. And now I had to go back to my ransacked flat. As I trudged back to the main road, I felt a prickle on the back of my neck like I, too, was being watched.

‘I love this guy,’ she said, her lips close to my ear, though the music wasn’t so loud that we couldn’t have a conversation. She had an Eastern European accent.

My laptop was sitting on the desk, plugged in to its charger. Beside it lay the iPad that had been stolen. The Bluetooth speaker, iPad and PlayStation 4 were back in their usual spots too. I picked up the laptop, turning it over in my hands. There was the tiny dent that I’d caused when I’d dropped it a few months before. There was the scratch on the back. I was sure that if I checked the serial number, it would match. This was my computer. The computer that had been stolen two days ago.

To be safe, I opened my virus-checking software and started a scan of the machine. All of a sudden, I felt sick. My skin went cold, all the way to my scalp,

‘No. More . . . sinister than that.’ ‘Sinister?’ I opened my mouth. But what was I supposed to say? As well as this apparently phantom burglary, someone

might have attempted to push Laura under a Tube train, and I thought I’d seen someone watching her. It all sounded very weak, and Sargent was already looking at me like I was unhinged.

‘A mix of sleeping pills and anti-depressants. Something called Zopiclone and . . . Trazodone, which is apparently prescribed for anxiety.’ She held up her phone. ‘I looked it up.’

‘She kept staring at the window. And then she started . . . jabbering, muttering and pointing towards the garden. It was really hard to work out what she was saying. Something about being followed, about a ghost.

That’s what she kept saying. And she said something weird about her skin, something about tarantulas and how her skin wouldn’t grow back. Her eyes were blank, kind of . . . cloudy.

‘Daniel. What the hell happened to you and Laura on that trip?’

Because the other side of the world wasn’t far enough away. Sunshine and distance couldn’t heal her, protect her or make her hate herself any less. Nor, she realised, could time. The skin she had shed was never going to grow back.

She had lain on her bed in her tiny room and stared at the wall, and as she listened to her heart pounding in her chest, the darkness creeping through her veins, cold and shivering and not aware she was crying until she felt the wetness on her face, she knew what she had to do.

‘Laura.’ She went rigid beneath the thin sheet. The voice was soft, close to a whisper. ‘It’s me.’ She knew exactly who it was. It was a voice she would never forget, a voice she had last heard rising in a scream, then abruptly falling silent. It was the voice of a dead woman. And she realised, in that moment, that the glimpses of black clothes and white skin that she’d seen following her, that she thought she’d imagined, must be real. The presence she’d sensed in the central London streets and among the trees at the end of Erin and Rob’s garden. It wasn’t her imagination. It was real. It was

...more

‘You mustn’t do it,’ the dead woman whispered. She was standing right by the bed now. Laura kept her eyes shut tight, the thin sheet forming a barrier in case the ghost turned hostile. ‘You mustn’t kill yourself yet.’ Laura was crying now. Crying from the memory of a decision that had changed everything. ‘I need you,’ the ghost said. ‘I need you to stay alive,’ and Laura threw the sheet forward, jerking upright, the pain in her skull gone. The ghost was gone too.

‘But she still believed Beatrice was real?’ ‘Yeah. And get this—she went to the local library and found out that a twelve-year-old girl had died in her house thirty years before. Was murdered, actually, by her dad.’ ‘My God.’ ‘I know. Laura said she was convinced for a while that her own parents were going to murder her. You’ve met them, haven’t you?’

A thin pink gown wrapped around a bundle of bones. Tears sliding down a hollowed-out cheek. Blood-stained fur and two pairs of glassy eyes . . .

When I thought back across the past few weeks, there were holes there, black spaces in my memory, pockets of time that I couldn’t account for. I paced back across the room.

No, it had to be real. Somebody else had damaged the front door. My bank account had been defrauded, and that was because my burglar had cloned my card. Unless it was me who used the cards. I shook my head.

There were very few pictures from our European trip because our camera had been in one of the backpacks we left behind in Breva.

In the photo, Laura was lying on a bunk, asleep, her arms wrapped around her chest, knees drawn up. The photo had been taken in the sleeper compartment of the Romanian train.

Hand trembling, I clicked. In the next picture, I was asleep in the other bunk, mouth ajar.

The two pictures from our night on the train weren’t there anymore. They had vanished.

She was seeing ghosts and I was imagining phantom photographs. I started to laugh. We really were the perfect couple.

she came back to me, if we were united again, I was convinced we would be able to recover from our experiences and fight anything else the world threw at us. We were a hundred times stronger together. In the days and weeks following our return to England, when everything at home had seemed so dismal, the two of us trapped in our own dark spaces inside our heads, barely communicating, I had lost sight of that. Laura had taken it further.

The old man stared up at the burnt-out house. ‘Yes, both the Sauvages are dead. They were trapped upstairs. Nothing the fire brigade could do.’ He walked away, muttering, ‘Terrible business. Terrible.’

The camera was positioned above the entrance to the front door of the flat. It was connected to an app on my phone and was triggered by movement. If anyone entered the flat the camera would start recording. As I left the flat I looked up at the camera and smiled.

My therapist is dead, I typed. And I need to talk to someone. I hope you understand x.

‘Alina’s other boot.’

Why was this house here, deep in the forest? I guessed it must have been the home of—what? A huntsman? A woodcutter? Some kind of ranger? A witch?

I somehow knew, as if I’d seen it in a dream, that the door would open if I pushed it. It did. It was stiff, heavy, but it swung open slowly, revealing a large open space.

a coat stand with a black jacket hanging from it.

I felt sick, wondering if I’d have the guts to tell Jake the rest of the story. If I would be able to tell him the truth about what had happened.

And then something hit me, knocking the breath from my body as I fell to the floor, forcing the knife from my grasp. It spun away across the carpet.

A second later and the dog—the black dog that had leaped out of the darkness—would have torn out my throat.