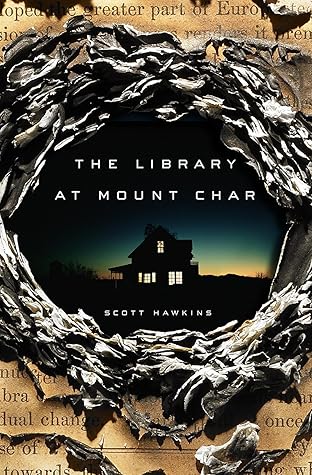

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Carolyn rose and stood alone in the dark, both in that moment and ever after.

“You can adjust to almost anything.”

“The librarians I know are into, like, I dunno, tea and cozy mysteries, not breaking and entering.”

She knew every word that had ever been spoken, but she could think of nothing to say that might ease his grief.

One such was the notion of uzan-iya, which was what they called the moment when an innocent heart first contemplated the act of murder.

The look in his eyes as he climbed inside the bull brought to mind another Atul phrase, “wazin nyata,” which was the moment when the last hope dies.

“No English,” Carolyn confirmed. She and Rachel spoke for a moment in a vaguely singsongy language that sounded like the illegitimate child of Vietnamese and a catfight.

Gradually he came to understand that this particular nothing was all that he could really say now. He chanted it to himself in cell blocks and dingy apartments, recited it like a litany, ripped himself to rags against the sharp and ugly poetry of it. It echoed down the grimy hallways and squandered moments of his life, the answer to every question, the lyric of all songs.

“With this particular species of crazy, you stop trying to make things better. You start trying to maximize the bad. You pretend to like it. Eventually you start working to make everything as bad as possible. It’s an avoidance mechanism.”

“Because wazin nyata isn’t enough. Not for him. This, though…I’m pretty sure that it’s the worst thing that ever happened to anyone, anywhere. Ever. I think it’s the worst thing that can happen, the theoretical upper limit of suffering. Despair and agony,” she said. “Absolute. Unending.”

“I’m very far now. Far from all of you, far from myself. I am in the outer darkness, you see.” She blinked, imploring. “I have wandered for so very long. You understand this much?”

“That’s the risk in working to be a dangerous person,” she said. “There’s always the chance you’ll run into someone who’s better at it than you.”

“In the service of my will, I emptied myself. It was long and long before I understood what I had lost, and by then it was gone forever.”

“I must send you into exile, that you may be the coal of her heart. No real thing can be so perfect as memory, and she will need a perfect thing if she is to survive. She will warm herself on the memory of you when there is nothing else, and be sustained.”

“Step down into the darkness with me, child.” Just that once, Father looked at her with real love. “I will make of you a God.”

“It has a price, though. In the service of my will, I have emptied myself.”