More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

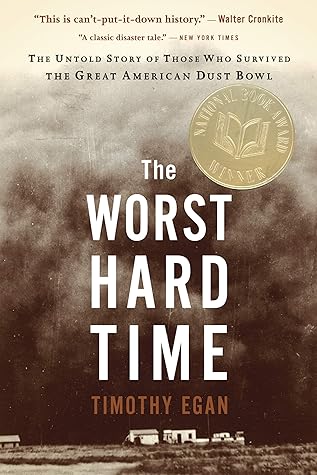

by

Timothy Egan

Read between

May 21 - June 26, 2020

The Panhandle was good for one thing only: growing grass—God’s grass, the native carpet of plenty. Most of the land was short buffalo grass, which, even in the driest, most wind-lacerated of years, held the ground in place. This turf had supported the southern half of the great American bison herd, up to thirty million animals at one point.

Settlement was a dare, on a grand scale, to see if people could defy common sense.

He noticed how the horses were lethargic, trying to conserve energy. Usually, when the animals bucked or stirred, it meant a storm on the way. They had been passive for some time now, in a summer when the rains left and did not come back for nearly eight years.

Droughts came and went. Prairie fires, many of them started deliberately by Indians or cowboys trying to scare nesters off, took a great gulp of grass in a few days.

When a farmer tore out the sod and then walked away, leaving the land naked, however, that barren patch posed a threat to neighbors. It could not revert to grass, because the roots were gone. It was empty, dead, and transient. But this was not something farmers argued about in meetings where they clamored for price support from the government.

He also knew he would not be able to find anybody who could provide answers, oral history, or a link between this mummified past and the desperation of the twentieth century. The Indians knew something, but they were gone, pushed from the plains before they could hand off a guide to living.

“Of all the countries in the world, we Americans have been the greatest destroyers of land of any race of people barbaric or civilized,” Bennett said in a speech at the start of the dust storms. What was happening, he said, was “sinister,” a symptom of “our stupendous ignorance.”

Americans had become a force of awful geology, changing the face of the earth more than “the combined activities of volcanoes, earthquakes, tidal waves, tornadoes and all the excavations of mankind since the beginning of history.”

Hoover had been leery of meddling with the mechanics of the free market. Under Roosevelt, the government was the market.

Aldo Leopold, had published an essay that said man was part of the big organic whole and should treat his place with special care. But that essay, “The Conservation Ethic,” had yet to influence public policy.

A kid from New York City, Arthur Rothstein, was just out of college, twenty-one years old, when Stryker sent him to Kansas, Texas, and Oklahoma in the spring of 1936. It was like sending George Catlin on one of the first explorations of the West, for Rothstein returned with images that most of America had never seen.

Inavale, Nebraska, where the Hartwells lived, is a ghost town.