More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 10 - March 8, 2020

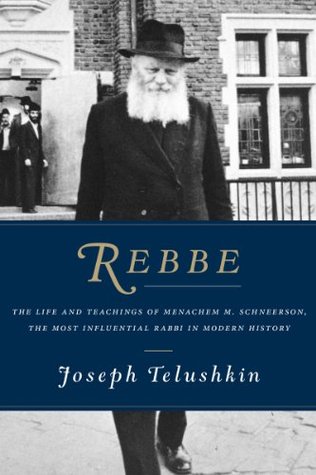

As Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson introduced what was in effect a new standard in Jewish life, an unconditional love and respect for all Jews, regardless of their denominational affiliation or non-affiliation.

This refusal to judge others based on their observance of Jewish laws, particularly ritual ones, was, and still is, a radical idea.

what many Chasidim sensed was that the mind-set of Menachem Mendel Schneerson was peculiarly congenial to the United States, something that the Frierdiker Rebbe—who understood that his movement’s future followers were going to be drawn from the United States and no longer from Belarus and Poland—must have felt as well.

Chasidim trust a Rebbe’s advice on such a variety of issues because they feel a Rebbe, in addition to having wisdom, has achieved a spiritual level of bittul ha-yesh, a nullification of his personal will.

Menachem Mendel Schneerson did not covet the position of Rebbe. Still, at some point, as yet undefined, it must have dawned on him, and likely on Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka as well, that whether he wanted it or not, he would likely be drafted for the position—and would not in good conscience be able to say no.

His loyalty to Chabad and to his father-in-law precluded his doing so. The Rebbe, I believe, understood, or came to understand during the course of 1950, that Chabad’s future viability depended on his becoming the movement’s leader.

What the new about-to-become Rebbe was conveying was this: If a Jew loves God but lacks love for his fellow Jews, that in itself indicates that there is something lacking in his love of God. On the other hand, if a Jew loves people, is concerned with “providing bread for the hungry and water for the thirsty,” that person can be brought to a love of God and Torah as well.

It was not enough, it was never enough, to simply practice Judaism by oneself or in an already religiously observant community; one has to bring others to embrace God as well.

“It’s the small acts that you do on a daily basis that turn two people from a ‘you and I’ into an ‘us.’”

the Rebbe’s most fundamental theological convictions: God is infinite, God is incomprehensible, and God is actively involved in the world.

AMERICAN JEWS CANNOT BE TOLD TO DO ANYTHING, BUT THEY CAN BE TAUGHT TO DO EVERYTHING.” —The Rebbe in conversation with Herman Wouk

“For if the exile was brought about through unfounded hatred, we will bring the redemption through unbounded love.”

The Rebbe believed that for a Jew largely uninvolved in the performance of the commandments, the journey to God begins with the performance of a single mitzvah.

The Mitzvah Tank campaign also highlighted the Rebbe’s belief that the performance of any mitzvah in and of itself, and even when performed by a person who is otherwise nonobservant (such as a Jew who puts on tefillin in a Mitzvah Tank and then goes off to eat an unkosher meal), has value. This belief was highly atypical in the Orthodox world of the 1960s and 1970s, although because of the Rebbe’s precedent, it is not as atypical today.

As the Rebbe intuited, there are many Jews who in their hearts do wish to become more involved but who on their own won’t do so; they simply need to be asked; they simply need to know how much they are wanted.

A Jew should never consider performing a kindness for another as beneath him- or herself or somehow less consequential than other religious acts, such as praying on Yom Kippur or studying Torah.

Other Jewish groups, both now and in the past, have placed their greatest stress on other commandments.

what he seemed to want most from his followers was for them to become leaders. To achieve that, he pushed them to become less, not more, reliant on him.

The gift the Rebbe gave his followers—which enabled them to touch and challenge people two and three times their age, with far more secular knowledge and professional attainments—was the belief that they were on a mission for something higher than themselves. To serve God. And that God would not have sent them on such a mission unless He believed in them. And the Rebbe would not have sent them unless he believed in them. And by carrying out their personal missions, these shluchim became leaders. They became visionaries, they became proactive. They became fearless.

the Rebbe, both in his public lectures and in his private interactions, emphasized that extraordinary attention must be paid to the words we use.

the extraordinary care he took both to avoid using negative words and to avoid speaking negatively of others.

In Chabad outreach, and in the Rebbe’s speeches throughout the postwar years, the emphasis was never on the Holocaust, but on simcha shel mitzvah, the joy of doing a mitzvah. This probably had to do both with the Rebbe’s naturally optimistic inclination and with a strategic assessment that the Holocaust does not ultimately provide a positive motivation for Jews to go on leading Jewish lives.

we are all familiar with the expression “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” The Rebbe, it would seem, at least when considering himself and his shluchim, thought differently, that the extra bit of effort might be exactly what is necessary to bring about the world’s redemption.

Since time is finite, the only way we can carry out all that we need to do is to utilize whatever time we do have to its full capacity; this means giving our entire focus, our full concentration, to whatever we are doing at that moment. Therefore, while working on one task, “we must regard anything else we have done before and anything that we are planning to do later as totally insignificant.”

What seems to have been unusual in the case of the Rebbe is that he regarded all Jews as family—and the affection that many people can maintain for family members with whom they have profound disagreements he could maintain for many thousands of people.

“Look always for that which you have in common with the other person and build that up.”

Yet another way in which the Rebbe kept disagreements from becoming personal was by almost always refraining from naming those with whom he disagreed.

the Rebbe regarded those with whom he disagreed as ideological opponents, not personal foes.

“I don’t speak about people, I speak about opinions,” the Rebbe liked to say.

The Rebbe said he was actually optimistic about American Jews: “The American-Jewish community is wonderful. While you cannot tell them to do anything, you can teach them to do everything.”

whether it was a question of a day, a few hours, or even minutes, the Rebbe pushed to see that if a task could be accomplished, it be accomplished as soon as possible.

Making God and His moral demands of human beings known to non-Jews was regarded by the Rebbe as equal in significance to promoting knowledge and practice of the commandments (mitzvot) among Jews, a universalist position that one does not find, to say the least, echoed widely in traditional Jewish circles.

An innovation of the Rebbe lay in expanding the search for spiritual and ethical lessons to the worlds of business, science, the professions, and even recreational activities such as baseball and board games.

the Rebbe believed that one should never fully give up on any human being.

In addition to an extraordinary memory, a distinguishing characteristic of the Rebbe’s teachings was his ability to draw out practical, day-to-day implications from almost all Jewish texts.

“If in a previous generation there were people who doubted the need of Divine authority for common morality and ethics, [and who believed instead] that human reason is sufficient authority for morality and ethics, our present generation has, unfortunately, in a most devastating and tragic way, refuted this mistaken notion. For it is precisely the nation which had excelled itself in the exact sciences, the humanities, and even in philosophy and ethics, that turned out to be the most depraved nation in the world. . . . Anyone who knows how insignificant was the minority of Germans who opposed

...more

the Rebbe always made a point of emphasizing that his opposition to Israel withdrawing from any of the lands it had won in the Six-Day War was rooted not in the sanctity of the land but solely on his conviction that such withdrawal would lead to Jewish lives being lost.

“I am completely and unequivocally opposed to the surrender of any of the liberated areas currently under negotiation, such as Judea and Samaria, and the Golan, for the simple reason, and only reason, that surrendering any part of them would contravene a clear psak din [legal ruling] in the Shulchan Aruch [the ruling cited above]. I have repeatedly emphasized that this ruling [on which I base my opinion] has nothing to do with the sanctity of Eretz Yisrael . . . but solely with the rule of pikuach nefesh.”25 That is why he opposed giving the Palestinians a homeland on the lands that Israel had

...more

In the Rebbe’s view, overconcern with Israel’s image and fear of antagonizing the United States had already cost Israel dearly, as illustrated by the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

The Rebbe’s dispute with the pro-demonstration activists in the United States did not derive from a differing assessment between the two sides on the nature of the Soviet Union. Both sides were in full agreement on the evil and antisemitic nature of the regime. The issue that divided them was what would be the most effective way to secure freedom for the Jews—public confrontations with the Soviets or behind-the-scenes diplomacy—or perhaps, as seems most probable, the pursuit of both, having different people doing different things, the Rebbe in effect being the “good cop” and the demonstrators

...more

To say that it would not affect a religiously observant activist to remain another ten years in the Soviet Union was a reflection of the Rebbe’s view that problems such as government harassment, economic poverty, and a lack of schools and peers for one’s children were prices that had to be borne if remaining in Soviet Russia—or any place where one lived—enabled one to educate otherwise ignorant Jews in the teachings and practices of Judaism.

the Rebbe saw it as part of his mission to correct a common misconception about science, that it offers clear and definitive answers. Thus, people commonly use expressions such as “Science proves. . . .” But science, the Rebbe argued, was never intended to prove things. Rather, what science offers are theories, hypotheses, and probabilities, “while the Torah deals with absolute truths.”

“Basically, the ‘problem’ has its roots in a misconception of the scientific method, or simply what science is. Thus, when it comes to dating the universe, we are not dealing with empirical science, which describes and classifies observable phenomena (such as different species of trees), but we are dealing with speculative science.

extrapolation, in which inferences are made beyond a known range, is far less reliable:

He did not tell scientists that they should accept the Torah’s account of Creation; he knew that such an argument would fall on deaf ears. What he wanted from the scientific community was the acknowledgment that evolution is a theory, a theory that does not have any “[irrefutable] evidence to support it.” Thus, the theory of evolution might well contradict the biblical account of Creation, but scientists should have the humility to acknowledge that it doesn’t disprove it.

What concerned him most was not that people found his views convincing but that they observed the commandments.

the Rebbe advocated education with even greater passion than do most American Jews, but the education he most espoused was religious education, the study, in particular, of the “three Ts”: Torah, Talmud, and Tanya (the basic philosophical treatise of Chabad). Regarding college education, particularly when carried out during the late teens and early twenties, when most Americans attend university, the Rebbe’s attitude was indeed negative,

he who sends his child to college during his formative years subjects him to shock and profound conflict and invites quite unforeseen circumstances” (emphasis added).

In instances in which a direct correlation existed between a person’s area of study and potential livelihood, the Rebbe was far more open to college attendance.

However, when no obvious connection between the course of study and future livelihood existed, as is frequently the case with those who concentrate in subjects such as history, sociology, and literature, the Rebbe opposed college attendance. Presumably, he felt that the students’ minds would be far more nourished by expanding and deepening their Torah knowledge.