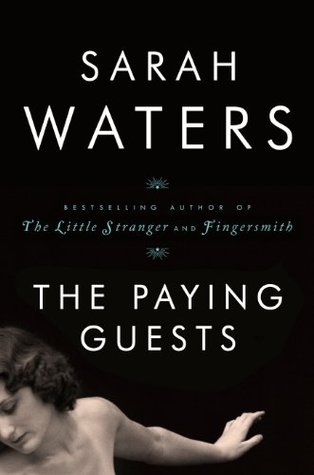

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

You’d never guess that a mile or two further north lay London, life, glamour, all that.

It wasn’t like beginning a journey, after all; it was like ending one and not wanting to get out of the train.

it was a mouth, as she’d put it to herself, that seemed to have more on the outside than on the

and the late-afternoon sunlight, richly yellow now as the yolk of an egg, was streaming in through the two front rooms as far almost as the staircase.

her hand. Once again, however, she dithered. Were biscuits absolutely necessary? She put three on a plate, set the plate beside the teapot—then changed her mind and took it off again. But then she thought of nice Mrs Barber, going carefully over the polish; she thought of the fancy heels on her stockings; and returned the plate to the tray. —

Frances caught herself thinking, as she might have done of guests, Well, they’re certainly making themselves at home. Then she took in the implication

and the little bell for summoning the whiskery spinster daughter. She quickly turned her back on that image.

‘Whether they’re genuine or not,’ she’d said, ‘they have your father’s heart in them.’ ‘They have his stupidity, more like,’

The gloss would fade in about five minutes as the surface dried; but everything faded. The vital thing was to make the most of the moments of brightness.

It was amazing, in fact, she reflected, as she repositioned her mat and bucket and started on a new stretch of tile, it was astonishing how satisfactorily the business could be taken care of, even in the middle of the day, even with her mother in the house, simply by slipping up to her bedroom for an odd few minutes, perhaps as a break between peeling parsnips or while waiting for dough to rise— A movement at the turn of the staircase made

unintimate proximity, this rather peeled-back moment, where the only thing between herself and a naked Mrs Barber was a few feet of kitchen and a thin scullery door.

Now the world seemed to her to have become so complex that its problems defied solution. There was only a chaos of conflicts of interest; the whole thing filled her with a sense of futility. She put the paper aside. She would tear it up tomorrow, for scraps and kindling.

She was at her truest, it seemed to her, in these tingling moments—these moments when, paradoxically, she was also at her most anonymous. But

I were to die today, she thought, and someone were to think over my life, they’d never know that moments like this, here on the Horseferry Road, between a Baptist chapel and a tobacconist’s, were the truest things in it. She crossed the street, swinging

Their friendship sometimes struck Frances as being like a piece of soap—like a piece of ancient kitchen soap that had got worn to the shape of her hand, but which had been dropped to the floor so many times it was never

There had been a pearl brooch on her lapel, and one of her gloves had had a rip in it, showing the pink palm underneath. My heart fell out of me and into that rip, Frances had used to tell her, later.

Christina and Stevie, who would almost certainly at that moment be eating some jolly scratch supper of macaroni, or bread and cheese, or fried fish and chips, and who might be heading off shortly to the sort of brainy West End entertainment—a lecture or a concert, cheap seats at the Wigmore Hall—to which Frances and Christina had

She had the tricked, trapped feeling she’d sometimes had with men in the past, the sense that, through no act of her own, she had become a figure of fun, and that whatever she did or said now would only make her more of one. And she felt the loneliness of

‘I’ll bet he’s warm just now.’ ‘What was that?’

How well she filled her own skin! She might have been poured generously into it, like treacle.

She knew that she herself would find it as hard to confess to an almost-stranger that she had seen a ghost as to admit to believing in elves and fairies. Which was why, of course, she realised, she

All I’m trying to say, I suppose, is that this life, the life I have now, it isn’t—’ It isn’t the life I was meant to have. It isn’t the life I want! ‘It isn’t the life I thought I would have,’

as if we’d gone helping ourselves to your clothes, and were wearing them all the wrong way.’

and the passers-by were a daytime crowd of idlers, invalids, children just out of school, women with toddling infants, elderly gents with dogs on leashes—the sort of people, she thought wryly, who’d be the first to get admitted to a lifeboat. How

don’t suppose he really meant to marry me. I don’t suppose

‘Well, my Yorkshire grandmother used to say that marriages are like pianos: they go in and out of tune. Perhaps yours and Mr Barber’s is like that.’ Mrs Barber smiled back

It isn’t worth it. You don’t know how lucky you are, being single, able to come and go just as you please—’

It was like a cure, being with Lilian. It made one feel like a piece of wax being cradled in a soft, warm palm.

It was not nothing. It was the crisis of her life.

gesture, an airy movement with her hand. It was an attempt, perhaps, at sophistication, as if to say that women made sapphic disclosures to her—oh, every other day.

Was this, she thought, what happened when one made friends with a married woman? One automatically got the husband too?—like a crochet pattern, coming free with a magazine?

Clearest of all, however, she saw Lilian, groping for the clasp of her suspender. She saw the silk stocking coming down, over and over again.

She had opened the window wide but left the curtains almost closed, and now and then a breeze stirred them, making the column of light between them blur and sharpen, widen and thin. The scents were those of the garden: sweet lavender, sharp geranium.

Some things are so frightful that a bit of madness is the only sane response. You

a drum-skin quiver at the base of her throat. They looked at each other in silence, and the moment seemed to swell, to be suspended, like a drop of water, like a tear . . .

was impossible, after all . . . But she returned to the bed, lay with her fingers over her heart, convinced that she could feel a stir of heat, a glow of blood—something, anyhow, that had been brought to the surface by Lilian’s hand.

But even as she nodded, even as she murmured, even as she lit that cigarette and leaned to fit it between his lips, a part of her, like a long, long shadow running counter to the sun, was leaning to Frances; Frances was sure of it.

It was as if a thread were fixed between them, continually drawing them back together. And there was another sort of thread, tugging

These people all have their claim on her. What’s mine, exactly? But as she began to feel almost glum about it,

‘He’s only taken a shine to me because I’ve taken a shine to you. It’s your shine, Lilian.’

Again she had the helpless, electric sense that the space between them was alive and wanted to ease itself closed.

Lilian was gone, sucked back into her marriage. For while Frances had been

changed. But they did not separate. They held the kiss, chaste as it was, until, by their very holding of it, it became unchaste; and in another moment again, still kissing, they had moved into an embrace, fitted themselves tightly together. With only the nightdress and wrapper on her Lilian might almost have been naked, and the push and press of her breasts and hips, combined with the yield and wetness of her mouth, gave the embrace a sway, a persuasion . . . It was like nothing Frances had ever known. She seemed to have lost a layer of skin, to be kissing not simply with her lips but with

...more

can’t let you go.’ It was like being parched, and touching water; like being famished, and holding food. ‘Please. Please. Just a little while longer. Just to kiss. I promise.’

And when Lilian cried out, their mouths were tight together; Frances took in the cry like a breath, and it became her own.

It doesn’t seem anything to do with him. It doesn’t seem anything to do with anyone but us, does it?’

‘My fingernails want you under them. The hairs on the back of my neck rise up whenever you go by. The stoppings in my teeth want you!’ They kissed, and kissed again. There was no self-consciousness between them, no sort of shame or embarrassment: they had passed through all that, she thought, their eyes glowing with triumph and wonder, as easily as runners breasting the ribbon at the end of a track.

But when I’m with Lilian I feel honest. I feel like a knot that’s been unpicked. Or as if all my angles have been rubbed smooth.’

we can’t let this bit of love go by. We

Frances asked herself, had she and Lilian done? They had allowed this passion into the house: she saw it for the first time as something unruly, something almost with a life of its own. It might have been a fugitive that the two of them had smuggled in by night, then hidden away in the