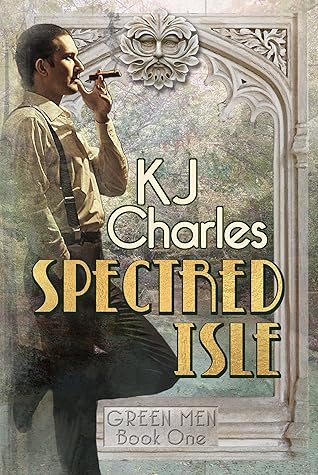

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

unaccountably noticeable at the corner of his eye and giving the irritating impression that it moved a tiny bit every time he looked away,

Enfield Chase,”

Geoffrey de Mandeville;

“The turncoat earl of Essex during the Anarchy,” Saul offered. “He changed sides several times between King Stephen and Empress Matilda.”

twelfth c...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

would enlighten him. Or, at least, tell him things.

Once neither claimant to the throne was prepared to trust him again, de Mandeville launched a rebellion and lived as an outlaw. He died excommunicate, and nobody would accept his body for burial except the mystical order of the Knights Templar.

“De Mandeville once had a manor house there, on a site called Camlet Moat.”

Nobody knows where the true Camelot was located. Perhaps it was the name of the court and not the castle; perhaps it moved with the king.

Camlet Moat to which all kinds of legends are attached.

The point is that legends cluster around important sites, such as holy wells.

Leonard Woolley’s excavations at Ur. The great Sumerian city had not caught the popular imagination, unlike Howard Carter’s work in the Valley of the Kings,

greensward.

was a stone obelisk.

a Georgian faux-ancient folly.

was forced to remind himself that the area was actually rather small. It didn’t feel small. It had the atmosphere of a much larger forest, with nothing at all visible through the trees and the green-brown haze of shrubs, ferns and brush. Once it had stretched over mile upon mile, and deer would have stepped through the thickets, unafraid.

He’d come to the water as its banks bent sharply in a corner, and it stretched away from him to left and right in near-straight lines.

It was fresh and clean here, and it made his heart lift in a way he hadn’t experienced in too long.

There was no birdsong.

Still, and absolutely silent except for his own pulse, which seemed somehow to be very loud indeed in his ears. He stood, and the wood stood around him, and quite suddenly he was afraid.

There were bright rags hanging off the branches of a tree. A lot of rags, and not all bright any more. Some were new, others fading, and now he could see that what he’d at first taken for swags of lichen or rotting leaves were yet more bits of cloth, mouldering away to nothing. He wondered for a second how the wind had brought so many rags to a single tree, and then saw that each was knotted on.

he’d nearly stepped into a well.

Glyde’s eyes were the colour of woodland: light brown, green-dappled, gold-flecked, fascinating.

He had green eyes,

so I wanted to sleep with him—

green eyes flecked with yellow, dried leaves on the surface of a pool-

You could drown in those eyes, I said.

The fact of his pulse,

the way he pulled his body in, out of shyness or shame or a desire

not to disturb the air around him.

Everyone could see the way his muscles worked,

the way we look like animals,

his skin barely keeping him inside.

I wanted to take him home

and rough him up and get my hands inside him, drive my body into his

like a crash test car.

I wanted to be wanted and he was

very beautiful, kissed with his eyes closed, and only felt good while moving.

You could drown in those eyes, I said,

so it’s summer, so it’s suicide,

so we’re helpless in sleep and struggling at the bottom of the pool

could feel how deliciously it would sluice a throat parched by heat and sun and the red dust of ancient pottery.

“No violent cramps, urge to vomit black bile, or bleeding from eyes, ears, or nose?” “Not more than usual, thank you.

cloutie tree?”

Clootie wells (also Cloutie or Cloughtie wells) are places of pilgrimage in Celtic areas. They are wells or springs, almost always with a tree growing beside them, where strips of cloth or rags have been left, usually tied to the branches of the tree as part of a healing ritual. In Scots nomenclature, a "clootie" or "cloot" is a strip of cloth or rag

How many people had tried to wash away their pain and desperation on this peaceful islet?

“You mean, can it minister to a mind diseased?” “Broken minds, broken hearts.”

they need healing as much as legs and arms, don’t they, even if the injuries are less visible. Ah... I think one might simply wash one’s face, you know. The water knows its business.

under cold water that blazed like flame.

thought he heard Glyde whisper something, then the cloth was lifted away.

his touch wasn’t priestly any more.

“The only question is, are you an actor or a puppet?” “Oh, a puppet.”

It had been too long since the last time; it had hurt too much.

“I don’t like the way I keep meeting you, and I don’t think puppethood suits you.”

Saul didn’t quite think about anything as he crossed the bridge back to the park, where the birdsong sounded deafening, or walked back to Cockfosters station. He didn’t begin to think, in fact, until he was safely on the train, at which point the utterly bizarre nature of the encounter dawned on him, like the belated realisation while shaving that a troubling memory was nothing but a dream. Except that, in this case, it had happened.

He’d wanted so much in that moment. Not just the touch, not just the promise those stroking fingers made to his skin, but the care with which they moved. The understanding in Glyde’s eyes. The kindness.

left with a feeling of something almost like absolution. It was a comfort, even if an illusory one, to imagine his sin and shame rotting away with the cloth, and Glyde had given him that when other men had spat.

mesmerism