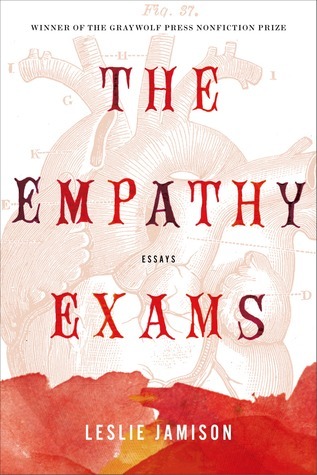

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

We are instructed about the importance of this first word, voiced. It’s not enough for someone to have a sympathetic manner or use a caring tone. The students have to say the right words to get credit for compassion.

Some of them get irritated when I obey my script and refuse to make eye contact. I’m supposed to stay swaddled and numb. These irritated students take my averted eyes as a challenge. They never stop seeking my gaze. Wrestling me into eye contact is the way they maintain power—forcing me to acknowledge their requisite display of care.

Other students seem to understand that empathy is always perched precariously between gift and invasion. They won’t even press the stethoscope to my skin without asking if it’s okay. They need permission. They don’t want to presume. Their stuttering un-wittingly honors my privacy: Can I … could I … would you mind if I—listened to your heart? No, I tell them. I don’t mind. Not minding is my job. Their humility is a kind of compassion in its own right. Humility means they ask questions, and questions mean they get answers,

Empathy requires knowing you know nothing.

Empathy means acknowledging a horizon of context that extends perpetually beyond what you can see:

We should empathize from courage, is the point—and it makes me think about how much of my empathy comes from fear.

This confession of effort chafes against the notion that empathy should always rise unbidden, that genuine means the same thing as unwilled, that intentionality is the enemy of love.

One comment from a stranger can’t reclaim years spent hating the body you live in.

Do I believe her? I nod. I tell myself I can agree with a declaration of pain without being certain I agree with the declaration of its cause.

It’s Othello’s Desdemona Problem: fearing the worst is worse than knowing the worst.

So you eventually start wanting the worst possible thing to happen—finding your wife in bed with another man, or watching the worm finally come into the light. Until the worst happens, it always might happen. When it actually does happen? Now, at least, you know.

The idea of the worm—the possibility of the worm—was so much worse than actually having a worm, because I could never get it out. There was no not-worm to see, only a worm I never saw.

“Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship,” Susan Sontag writes, “in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.” Most people live in the former until they are forced to take up residence in the latter.

It’s about this strange sympathetic limbo: Is it wrong to call it empathy when you trust the fact of suffering, but not the source? How do I inhabit someone’s pain without inhabiting their particular understanding of that pain?

In a New Yorker article titled “The Itch”—like a creature out of sci-fi—Atul Gawande tells the story of a Massachusetts woman with a chronic scalp itch who eventually scratched right into her own brain, and a man who killed himself in the night by scratching into his carotid artery. There was no discernible condition underneath their itches; no way to determine if these itches had begun on their skin or in their minds. It’s not clear that itches can even be parsed in these terms. Itching that starts in the mind feels just like itching on the skin—no less real, no more fabricated—and it can

...more

When does empathy actually reinforce the pain it wants to console? Does giving people a space to talk about their disease—probe it, gaze at it, share it—help them move through it, or simply deepen its hold?