More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 21 - July 26, 2020

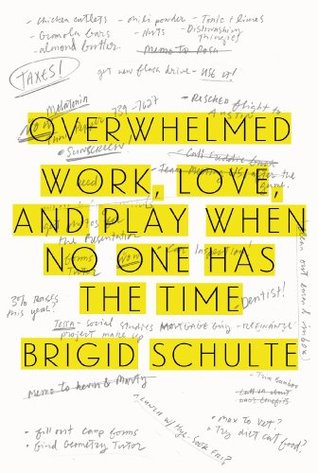

Because this is how it feels to live my life: scattered, fragmented, and exhausting. I am always doing more than one thing at a time and feel I never do any one particularly well.

Some appliance is always broken. My to-do list never ends.

“I read the paper, typically at midnight, in bed … I have no time in the morning. I do everything in the house. I pay all the bills, take out the trash, I’ve got the dry cleaning in the car. So in the morning, when my husband is reading the paper, I’m in constant motion getting the girls to school and getting ready for work. Men are different. They could read the newspaper with piles of laundry all around them. I can’t.”

To Hunnicutt, people in the modern world are so caught up in busyness they have lost the ability even to imagine what leisure is.

Instead, Robinson maintains that we “exaggerate” our work hours to show how important we are. His studies find that we sleep more than we think. We watch too much TV. And we’re not nearly as busy as we seem to feel.

Robinson has found that people spend the most time walking in Spain, relaxing in Italy and Slovenia, and watching TV in Bulgaria. In the United States, people spend more time on computers than those in other countries, volunteer more, and spend the most time taking care of children and aging adults.

“Exercise is leisure.” Every time I read the newspaper he swipes it with the highlighter. “But that’s my job.” “Reading is leisure.”

All of that time strain cost businesses and the health-care system an estimated $12 billion a year in 2001 alone. “The link between hours in work and role overload, burnout, and physical and mental health problems,” according to the report, “[suggests] that these workloads are not sustainable over the long term.”

A whole new field of research is beginning to look into why the overwhelm matters. At what point does role overload lead to burnout and fatigue at work? When does it begin to tax the family system? How much of it is required before a physical or emotional breakdown occurs?

This was about sustainable living, healthy populations, happy families, good business, sound economies, and living a good life.

“People don’t have as much mental space to relax in a work-free environment. Even if something’s not urgent, you’re expected to be available to sort it out,”

That mental tape-loop phenomenon is so common among women it even has a name. Time-use researchers call it “contaminated time.”

One’s brain is stuffed with all the demands of work along with the kids’ calendars, family logistics, and chores. Sure, mothers can delegate tasks on the to-do list, but even that takes up brain space—not simply the asking but also the checking to make sure the task has been done, and the biting of the tongue when it hasn’t been done as well or as quickly as you’d like.

“It’s role overload,” she explains. “It’s the constant switching from one role to the next that creates that feeling of time pressure.” When all you’re expected to do is work all day, you work all day in one long stretch, she says. But the days of the mothers she studied were full of starts and stops, which makes time feel more collapsed:

Gone is the “pure” leisure of the adults-only coffee klatches, bridge parties, and cocktail and dinner parties of the 1960s. Gone, too, is much of the civic volunteering. Weekend activities often center on kids’ sports, cheering on the sidelines, or educationally enriching activities, like trips to the museum or zoo or schlepping them to cello lessons.

Women’s leisure tends to be fragmented and chopped up into small, often unsatisfying bits of ten minutes here, twenty minutes there that researchers call “episodes.”

But for years time studies have shown that women’s time is more fragmented than men’s time. Their role overload, juggling work and home, has been greater and their responsibilities and “task density” more intense.

In his studies, he usually finds men do one and a half things at a time. Whereas women, particularly mothers, do about five things at once. And, at the same time, they are caught up in contaminated time, thinking about and planning two or three things more. So they are never fully experiencing their external or their internal worlds. And if you are never really here or there, then what kind of life are you living? “It is a problem,” he said. “It is often very difficult for women to be able to live in the moment.”

“Look, if you design work around someone who starts to work in early adulthood and works full force for forty years straight, who have you just described? Men,”

“We have organized the workplace around men’s bodies and men’s traditional life pattern. That’s sex discrimination.

Though Congress passed the Pregnancy Discrimination Act in 1978, EEOC records show pregnancy discrimination claims are actually on the rise.

Delay can also mean that women simply run out of time, what the economist Sylvia Ann Hewlett calls a “creeping non-choice.”

“You want equality in the workplace? Die childless at thirty. You won’t have hit either the glass ceiling or the maternal wall,” she says.

The veto of the child-care bill set the stage for unpaid medical leave and all subsequent U.S. family policy.

the United States ranks dead last on virtually every measure of family policy in the world.

while the Dutch government is promoting the concept of the “daddy day,” with each parent working overlapping four-day workweeks so that children are in care only three days a week.

helped shape what would become: Child care in the United States today is a disaster.

While there is certainly good quality care, it is rare, wildly expensive, difficult to find, and even more difficult to get in to, with waiting lists that can last years.

“The bottom line,” wrote Cali Yost, a consultant who helps companies devise business strategies for better work-life “fit,” “is that you benefit when the parents you work with have support.”

She sent me surveys showing that millennials would rather be unemployed than stay in a job they hate, that they expect to change jobs often and to work in more collaborative, democratic workplaces, not the command-and-control totalitarian regimes of the ideal worker.

has found that both men and women millennials have no plans to work themselves into the ground and to the nether edge of their fertility, like older generations.

was discovering that the women who left weren’t staying home with their children, as everyone assumed. They were still working, just in workplaces with more give.

Unlike manual laborers, knowledge workers have about six good hours of hard mental labor a day,

Perhaps a manager hadn’t expected an immediate response at 3 a.m., but the junior recipient might worry that the manager did—something that Leslie Perlow, Harvard Business School professor and author of Sleeping with Your Smartphone, calls part of the merciless “cycle of responsiveness” that makes work feel intense, unending, and all-consuming.

Even during the Great Recession, when more men began losing their jobs and more women took up the mantle of family breadwinner, time-use studies found that the division of domestic labor became slightly more fair, but only because working mothers stopped doing as much, not because unemployed fathers did more. And what did those unemployed fathers do with that extra time? They relaxed.

that men feel happier when their wives are present, but that women do not necessarily feel the reverse.13 It might also explain his finding that men feel happier at home, and women when they go to work.

They tend to do only chores they like and tend to care for their kids only when they’re in a good mood. What’s not to like? For women, however, home, no matter how filled with love and happiness, is just another workplace.

Tom became the fun parent, wrestling with the kids, mugging for the camera, changing a few diapers. And I, always the one behind the camera and nowhere in all the photo albums, did the invisible drudge work.

“It’s natural for mothers to work. It’s natural for mothers to take care of children,” she says. “What’s unnatural is for mothers to be the sole caretaker of children. What’s unnatural is not to have more support for mothers.”

“What’s different today is that the workplace is no longer compatible with being a mother. It’s as simple as that.”

Middle-class parents are now so “child-centered” that they may be fostering a “dependency dilemma” and raising youths who can’t think, make decisions, and venture out on their own.

American mothers, on average, have about thirty-six minutes a day to themselves.

Well, first, they say, Americans seem to value achievement above all, and Danes make it a priority to live a good life.

Most Danes also have six weeks of paid vacation every year, one of the most generous vacation policies of any in the world,9 and, unlike Americans, most people take every minute of it.

men are taking leave, they’re starting to recognize how busy it really is to be home and understand why their wives are tired,” Søren says. “And my relationship with my sons is so much stronger from taking care of them. That will make a difference as they grow up, that their father was there.”

After six months, the government guarantees every child a spot in an early childhood development center and, for school-age children, in an after-school program.

consumed by work, the drudgery of keeping house, and the hard joy of raising young children, she felt the life draining out of her.

But she felt lost. “I found myself becoming boring. And sad. My life had shrunk to these two areas: work and caregiving,”

The brain dump is like jiggling the handle. “If your to-do list lives on paper, your brain doesn’t have to expend energy to keep remembering it,” Monaghan said.

“We’ve lost touch with the value of rest, renewal, recovery, quiet time, and downtime,”