More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

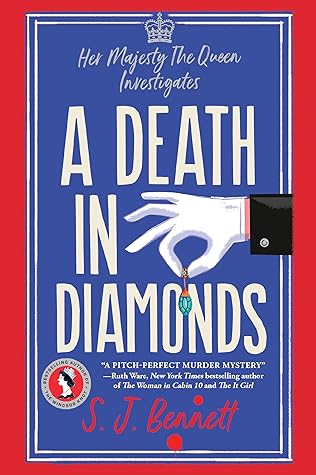

S.J. Bennett

Read between

January 21 - February 18, 2025

‘We need the kind of courage that can withstand the subtle corruption of the cynics so that we can show the world that we are not afraid of the future. It has always been easy to hate and destroy. To build and to cherish is much more difficult …

She had work to do when she got home, because it was clear that someone from inside her closest circle had been trying to sabotage this visit. Her response would be delicate and difficult, and she wasn’t sure who she could trust.

She had a strong constitution and decent stamina, was happy to work to a punishing schedule and ate almost anything that was put in front of her. However, shellfish were a rare but firm exception. One simply couldn’t fulfil one’s duties if one was doubled over with stomach cramps; her Private Office always made that clear. Nevertheless, last night she had been served six oysters à la sauce mignonette avec fraises et champagne, as if nothing had been said.

But there had also been the question of the missing speech.

It was a reminder that she spoke fluent French and a hymn of praise to the Entente Cordiale that bound two nations whose joint sacrifices had won a war against terrible odds.

By a stroke of luck, she had remembered that one of the later drafts of the original had come back from the typing pool at Buckingham Palace with a couple of excellent suggestions, in perfect, idiomatic French.

That temporary loss of the original, on its own, one might have put down to misfortune. But all copies and carbons? Really?

Someone most definitely did not want this visit to succeed. Someone in her own circle. Someone she had always trusted implicitly until tonight.

There were moments I wondered if they were going to swallow me whole.’ Sir Hugh Masson smiled as if her observation were merely a joke. He hadn’t been on the receiving end of that tidal wave of attention.

Radnor-Milne, her press secretary. Solid, traditional and dependable, they were chief among ‘men in moustaches’, as Philip called them – a collective term for the old guard the Queen had inherited from her father.

Urquhart was always absolutely certain that the British monarchy was the best institution in the world and the answer to almost any problem, even fashion-related. The Queen found it quite challenging to live up to such high expectations.

The press secretary wore a thin black line of facial fuzz modelled on the actor David Niven’s, in an attempt to suggest the actor’s military derring-do and suave urbanity.

Gone were the days of gunship diplomacy, when the old imperial powers could sail in and sort out problems abroad with a little show of muscle.

I know it was the German ambassador because he has the most frightful breath. Somebody really ought to tell him at some point. Not ideal for a diplomat.’ ‘I’ll pass the news on,’ Sir Hugh promised. ‘Not the bit about the breath.’ ‘Oh, that, too, ma’am. The Foreign Office will be delighted. Thank you.’

The men in moustaches all seemed equally aghast, just as they had done two days ago when her speech went missing. These were men whose service her father had prized, and she relied on them completely in order to carry out her job. One of them, she now knew, was lying to her. What about the other two?

She was the Queen’s dresser and more: her original nursery nursemaid, her confidante, the only person except her sister to have shared a childhood bedroom with the young princess, and the only one trusted nowadays to prepare and preserve her clothes.

Perhaps to make up for it, Mr Amies had put her in this shimmering silver column, which was just the sort of thing Marilyn Monroe might pick. Could this femme de trente ans get away with it?

She missed the comforting swish of net skirts.

She had been the sweetest thing to talk to, though. Marilyn was staying near Windsor at the time, and they talked about how nice it would be to meet up there too, not that either of them had the time. The Queen had the impression of a bold but fragile creature, like a young racehorse or a wild deer.

To everyone but the Queen, Prince Philip was ‘the Duke of Edinburgh’, or ‘sir’. He didn’t have a Bobo of his own to call him by a nickname and be treated as a trusted friend.

Two bodies, found in one of those little mews houses off the Old Brompton Road. It was all over The Times and the Daily Express.’

Just that it was a man and a woman, and she was no better than she should be. The awful thing is, it seems almost certain the Dean of Bath did it, or one of his guests.’

although they say he had a good war – so not that mild-mannered.’

Outside the room, at the top of the stairs, a small group was gathered. It consisted of the ambassador, two military equerries who assisted the royal couple in their public duties, Sir Hugh and Philip’s new private secretary, all ready to accompany them down. They were speaking in low voices but the words ‘Cresswell Place’ were audible.

Rather, the people who came back with the dean that night were all above board.

The awkward thing is, according to the press reports, the dean told the charlady not to clean upstairs the next day, as she usually did. He then returned to Somerset, and she only discovered the bodies when she went upstairs a week later.’

Nevertheless, her new dress sparkled obediently under the lights and her cheeks grew numb from smiling.

She had spent a joyful evening with the children and another hour playing with them this morning. They were keen to know about their gifts, which were inevitably too delicate to play with, but they soon forgot about them anyway in a ridiculous game of chase with their father, who was just as happy to be in their company as they were to have him back.

A wartime Spitfire pilot had once said every landing was just a controlled crash, really.

I have literally seen the man upend a glass on a piece of paper to transport a spider safely outside. Admittedly, he did see some horrors in Germany, but war is war, isn’t it, and quite a separate thing?

‘Clement told Cissy that the police showed him a picture of the diamonds, in case he knew where they came from. Of course, he had no idea, but he said the tiara was made up of roses and daisies in pink and white diamonds, with pale green peridots for the leaves. It’s quite an unusual combination and it reminded me so much of the Zellendorf tiara, from ’twenty-four. Cartier, very delicate, made for Lavender Hawksmoor-Zellendorf. It was supposed to resemble an English country garden. So pretty.

Anyway, it disappeared. Such a pity as it’s a lovely piece.’

What I meant to say was, if it is the Zellendorf, how on earth did she get hold of it?’

‘Cresswell Place. Anything goes on in that street. I think it’s exactly the sort of place you’d find a body and stolen diamonds.’

There’s an artist who hosts these fabulous little parties. Tiny mews house, like a doll’s house, really. You can hardly squeeze everyone in. They play the saxophone and dance on the stairs, it’s terribly funny. You never know if you’re going to be talking to a stockbroker or a demi-mondaine, or a spy.

Perhaps Margaret harked back to it because she really didn’t have one of her own, whereas the Queen couldn’t remember exactly how many she had access to.

On a good day, Margaret was the soul of generosity.

Nothing short of his own deathbed would keep George Venables away from something he really wanted.

Darbishire happened to know, because his uncle Bill was interested in etymology, that ‘mew’ referred to the moulting feathers of birds of prey, and the first mews – on the site of the present National Gallery in Trafalgar Square – was built to house the king’s hunting hawks while they moulted.

From hawks to horses, and from housemaids to Hooray Henrys.

But now, it seemed they were good enough for the Dean of Bath and his ilk. And for men with their high-class escorts dripping in diamonds.

Len Woolgar was six foot four, built like a brick shithouse, and unbelievably lazy for a man in mint condition. Put him in a rowing boat on the river and he was a demon – practically Olympic standard, so they said at the Yard, which was why he’d joined the force. The Metropolitan Police boat crew was top class. But put him on an actual police job, requiring thought and dedication to duty, and he was a liability. He was usually hungry. He would be now, but he’d had two egg sandwiches for tea before they left. A third created an unsightly bulge in the pocket of his coat.

Woolgar would miss everything, guaranteed.

The sergeant had beaned himself on the low door lintel again. You’d think, being six foot four, you’d learn to duck eventually.