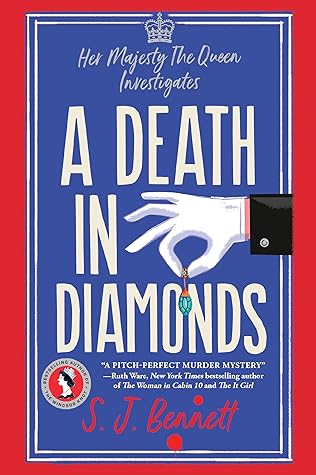

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

S.J. Bennett

Read between

January 21 - February 18, 2025

It was furnished with two rickety card tables and bits of old mahogany furniture that still showed evidence of a dusting with fingerprint powder.

You wouldn’t necessarily expect a senior member of the Church of England to be a demon with a cocktail shaker but, having met the man, Darbishire suspected he probably was.

The dean had treated them to a cocktail of his own construction featuring lemon juice and vodka. He claimed that was the cause of his headache the following morning and the reason he told the charlady not to linger any longer than strictly necessary, and not to clean upstairs. ‘She’s noisy. She rattles round the place like a Sherman tank. I don’t make a mess.

The guests that night had comprised a university professor who had been friends with Clement Moreton since his Oxford days, a widely respected circuit judge and a canon at Westminster Abbey.

Between hands of canasta, Moreton and the other three men went upstairs once each to use the facilities. There was no lavatory downstairs – no room for one.

Darbishire’s own visit to the Artemis Club yesterday had proved a disappointment. It sounded a grander institution than it was, physically at least – which was little more than a doorway off a street near Piccadilly, leading up to a few rooms for drinking and gaming and a private dining room.

Anyway, pool or no pool, membership of the Artemis included half the aristocracy and most of the Cabinet.

There was simply no way to murder two people upstairs in the way it was done and come down those open stairs without your physical appearance afterwards being observed by all concerned. So, either they were all in it together or the guests, at least, were innocent.

Moreton swore blind, or as much as a churchman ever did, that he never entered this room. His story was that the rental agency told him it was used for storage by the landlord and kept locked. He claimed he tried the door once and the handle rattled uselessly, as he expected it to. He didn’t need the space so didn’t worry.

If the char didn’t normally go in to keep it clean, who did?

But the inspector didn’t trust easy answers. He tended to ask questions until he got the hard ones.

In his forties, with the slicked-back hair of a Mediterranean or South American, the male victim had been identified by the papers in his pockets as Dino Perez from Argentina.

‘If she did, why didn’t she scream the bloody house down while she was doing it? Nobody on the street heard a peep. They all heard the char clear enough a week later.’

‘She was washed before she was put in position,’ Darbishire added. ‘Curious, no? Not all over, but enough to get rid of whatever blood was on her, which would’ve been mostly his. Wet towel dumped beside the bed.

Which is why the Artemis crowd were in the clear. None of them would have had time for all the artful arrangement, and to clean themselves up too. Or the opportunity to hide the girl’s missing dress and the stocking used to strangle her.

Her peroxide hair, soft and curled and lacquered into a sophisticated style, looked horribly out of place against the skin.

Moreton said he couldn’t remember seeing if the bolt was in place before heading home to his cathedral on the Monday morning, so it was probable that they had escaped via the little yard.

He wondered about the main witness that night: the young woman in the mews house opposite, up all night with her baby, who saw the comings and goings of Perez and Fonteyn, the dean and his guests. Her statement fitted in with the reports of taxi drivers and the suspects themselves, so she wasn’t making it up.

Once again, he wandered down to the end of the street, to get a sense of the yards behind the houses and their relationship to the gardens of the grand villas beyond.

The killers may have escaped across a series of yards until they were further down the street, but it seemed more likely they went straight over the ivy-covered wall of number 44 into the garden behind.

Eisenhower was supposed to have a little tour before the official introductions, but the King and the family were sitting out on the terrace when he saw the general’s party heading their way. The King knew it would cause a terrible fuss if the general was made to encounter them au naturel, like that, without warning, so he got them all – the Queen and the young princesses too – to get down on their knees and hide under the tablecloth until the party was out of sight. They were hooting with laughter.

The press secretary’s slim moustache wiggled in irritation. He had indeed checked everywhere obvious in the filing room, where the absent Fiona worked occasionally.

Her official title was Assistant Private Secretary and she assisted them all, but she was especially useful – although ‘useful’ was a loose term, in Fiona’s case – when it came to helping the deputy private secretary set up royal visits or manage Her Majesty’s correspondence. She was very easy on the eye, but paperwork was not her strong point.

‘Tell her the American president will call in twenty-five minutes, at twelve instead of four, and we know that’s not what we agreed but there’s not much to be done about it. She can make it to her desk if she runs, or of course we can have a telephone brought to her, but I imagine she’ll want privacy.’

Have you seen Her Majesty run?’ ‘No, sir.’ ‘Well, she does. She likes the exercise. You should see her when one of her dogs goes off after a rabbit or the children get too close to the lake.’ ‘Yes, sir.’

She was grateful to have been her school’s cross-country champion, but she was still out of breath.

‘We have twelve minutes. Odds on we can make it in ten. Sugar, off we go.’ For a moment, Joan assumed that Sugar was a nickname for the woman who had accompanied the Queen behind the screen, but it turned out to be a corgi, who had been lounging in front of a fireplace. The dog cheerfully shadowed her mistress at a brisk trot as they set off back across the palace.

Her Majesty was a disconcerting mix of perfectly normal and hypnotically familiar.

There was an odd modesty about her for someone whose image was so famous.

What she lacked in vanity she made up for in self-possession.

In the tight proximity of the creaky lift, with the clock running down, she recognised a kindred spirit.

She didn’t understand why other people had trouble recalling the images they had recently seen.

Like her father, she’d been able to do it all her life. He didn’t understand the problem, either.

‘Mmm. And you speak French fluently?’ ‘I do. My mother was French. I also speak German.’

She was the great-niece of a duke, one of his own distant cousins, and an excellent horsewoman with a weakness for cocker spaniels and couture fashion she couldn’t afford.

It was inevitable that the men in moustaches would provide acute resistance to a girl with an Irish name, a typist, no less, taking her place alongside them. But the Queen needed an ally, someone outside the close-knit institutional world she had inherited from her father.

Willis gave a friendly smile. He had a record of helping out with reluctant witnesses. His slick good looks and a kindly manner seemed to have a special effect on women of ill repute.