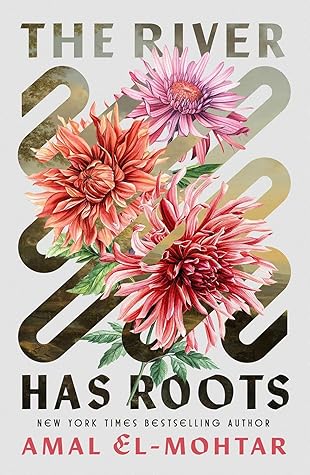

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

There was a time when grammar was wild—when it shifted shapes and unleashed new forms out of old.

What is magic but a change in the world? What is conjugation but a transformation, one thing into another? She runs; she ran; she will run again.

spring bluebells mix with autumn asters, and towering cattails scatter frosted seeds over beds of blooming marigolds.

and they bend towards each other like dancers, or lovers, reaching out to clasp each other.

The river may conjugate everything it touches, but the willows translate its grammar into their growth, and hold it slow and steady in their bark.

the sweep of their twisted crowns, reminds you of something, or someone, you’ve lost—something, or someone, you would break the world to have again. Something, you might think, happened here, long, long ago; something, you might think, is on the cusp of happening again. But that is the nature of grammar—it is always tense, like an instrument, aching for release, longing to transform present into past into future, is into was into will.

And if they sometimes meant things less pretty than those names suggested, well, there are always things lost in translation, and curious things gained.

What the town of Thistleford gained from its proximity to Faerie was obvious: prosperity, merriment, uncommonly good weather. What it lost was negligible—the cost of doing business.

But Esther and Ysabel Hawthorn had voices that ran together like raindrops on a windowpane. Their voices threaded through each other like the warp and weft of fine cloth, and when the sisters harmonized, the air shimmered with it.

Esther was thoughtful and gregarious, and while Ysabel had a laugh loud and easy as barrel-tumbled apples in the fall, she was in fact very shy.

Taste is a kind of language, and siblings speak it with a forked tongue.

As entwined as Esther and Ysabel were, there came a point in their childhood where their interests diverged, and, like the Professors, they loved each other across the gap between them.

Besides”—she smiled, reaching up to touch one’s trunk—“surely the river brings them all the news worth telling.” “Only from one direction,” said Esther, watching the water flow.

Ysabel smiled like a page turning.

They settled on “The Dowie Dens of Yarrow,” and if the willows bent their branches towards them as they sang, trailed them even lower into the water, the sisters never noticed.

He had gone to one of the great universities—Esther refused to remember which—and returned speaking both Latin and poetry, which he saw fit to share as often as he could though he plainly spoke neither very well.

Rin was a feeling, a lightness in her step, a burr in her throat; some days she thought she’d made them up inside her head, so difficult was it to put words to them.

but no one who’d set out on purpose to travel there had ever returned, and opinion was divided on whether that was because Arcadia was too delightful to leave or too dangerous to survive.

Their voice made Esther think of weather, of winter, of woodsmoke: something cold but bright, burning and fragrant, curling into the air before vanishing. They were utterly strange and utterly beautiful, in a way that Esther yearned towards because she didn’t understand it, the way she yearned towards horizons and untrodden secret paths in unfamiliar woods.

She couldn’t put words to the look on Rin’s face. She only knew, very sharply and deeply, that she wanted to go on being the cause of it.

Esther looked at her sister—her beautiful, brilliant sister, talented and generous and funny and kind—and felt her fingers curling into fists at the thought that all the summer sunshine of her could dim for want of being seen by the likes of Samuel Pollard.

“Bel,” she said helplessly, around the fire in her throat. “Queen of ducks and angels. You shall have poems written to you with a quill on fire. You shall have songs sung to you by enchanted harps. Whole branches of grammar will be invented only to praise you.”

“Ysabel Hawthorn,” she said, and she could not keep the heat from her voice, “demand better than to be worshipped by a crumb.”

but the common folk will cling to their superstitions while the city folk crave anything that comes with a stamp of rustic authenticity.

Esther launched into “John Barleycorn” before Ysabel could say anything—a very charming song, beloved in the west country, which is either about the planting, reaping, and milling of barley or about the ritual consumption of a man brutally murdered several times over. Esther sang it very much as the latter.

There are lands that are near to us temporally but far from us geographically: we can be certain that at this moment, in Italy, someone is sitting down to their breakfast with a newspaper dated roughly the same as ours, though we cannot expect to reach them in time to join them for the meal.

Rin closed their eyes, and bent their forehead to hers. They stood that way, holding hands and leaning towards each other like the Professors, while the Modal Lands hummed around them.

“Since this afternoon?” they murmured, looking at her the way she sometimes looked at sunsets, or the afternoon light winding its way through willow leaves.

Rin looked amused; it pleased them to be only one of Esther’s several passions, on roughly equal footing with damson jam and the patterns in riddle songs.

The song says, this thing you are used to, it has a past, and that past is part of it; what the cherry was before the cherry is part of the cherry.

The song says, this thing you are used to, it has a future, and the future is part of it, too.”

If you’ve ever looked into running water at midday and been mesmerised by the play of shadows over stones, and how even the sound of the water running seems, somehow, to have absorbed sunshine scattered through lines of leaves and grasses—if you’ve ever stood on a moor in the west country and watched daylight flash and vanish over the green and granite of the land—you might have a sense of how Rin looked as they listened to Esther, hope and anguish rippling through and around each other on the high pale planes of their face.

Esther gazed at her hand, and wondered at the grammar of it—not the shift of hair to jewels, but of woman to wife, so quickly, so gently.

She felt as if she could conjugate grammar with her joy alone, as if she could reach up, grasp the sky, and shake the darkening sheet of it into dawn.

The River Liss is always changing. It is one of the several enchantments of grammar that you can hear those words, the River Liss is always changing, and take it to mean it is changing itself, its length and breadth, its depth and its bends—or you can hear those very same words and ask, Changing what?

Perhaps you thought we would not enter Arcadia in this story; perhaps you thought all that business about riddles and time and distance was a sort of carving the bend of the tale away from it, a way of saying that Arcadia is purely unknowable to mortals, except in the case of its emigrants, like Rin, with whom you would grow familiar through their sojourn into our realm. You were not wholly wrong; any part of Arcadia we glimpse in this tale becomes less Arcadia the longer we look at it, and so in deference to our story’s geopolitics, we shall not be staying long.

She had never been so far from her parents that her voice couldn’t reach them.

She felt some stirring in her heart that cautioned her against answering the question; lost felt like a shifting, chancy word, a dangerous word to apply to oneself in Arcadia.

“From the mouths of babes! Well, why not, after all. If that word keeps chasing me down perhaps it has something important to tell me.”

It hurt Ysabel that Esther kept wanting to go back to that place that had so frightened them; it hurt Esther that Ysabel wanted nothing more to do with the most interesting thing that had ever happened to them.

They made it the way children sometimes make up a language to hide from adults, all invented vocabulary tacked on to borrowed syntaxes, when they know, but cannot yet explain, what grammar is.

There was something on her body, something somehow both constricting and comforting, and she could not bear the contradiction—that she was trapped, and this was good, but she was also free, and this was terrible.

Their eyebrows and hair were rimed stiff; their eyes were wholly black, and their whole aspect was of a vicious blown snow, the kind of dry, cutting powder that billows in the wind like sand and cuts cold and hard against the skin of anyone unfortunate enough to be caught in it.

Rin tightened their grip, and braced. The swan became fire, then snow; the snow became lightning, then thorns. Rin held the burning, scorching, stabbing shapes of her closer and closer, winced and bled the bright, clear blood of Arcadians over her, while Agnes muttered grammar forwards and backwards, coaxing the truth of the woman back into memory and flesh.

“I’m not afraid of that. She’s my sister,” said the woman again, but more quietly. “I would die for her. If I’ve really died … I want to have died for her.” “And I,” said Rin, softly, “only want you to live for me.”

I want to be with you. But I was an elder sister before I was a wife, and for longer, and that’s a shape I can’t easily shake.”

Most music is the result of some intimacy with an instrument. One wraps one’s mouth around a whistle and pours one’s breath into it; one all but lays one’s cheek against a violin; and skin to skin is holy drummer’s kiss. But a harp is played most like a lover: you learn to lean its body against your breast, find those places of deepest, stiffest tension with your hands and finger them into quivering release.