More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 22 - October 9, 2020

The Daleks’ Master Plan was the big Hartnell epic that was really good and missing.

The fifth episode involves some bizarre comedy involving Daleks, mice, and the possibility of mice inventing teleporters (Yes. Douglas Adams did watch this at the age of thirteen. Why do you ask?),

Thought of like this, The Daleks’ Master Plan isn’t five and a half hours long. It’s four months long, counting Mission to the Unknown. And as I’ve been saying, really it’s longer than that; it’s been paying off plot threads that started way back in The Time Meddler.

First of all, let’s rubbish the idea that this is a twelve-part story. It’s not. It’s really about four separate stories, two of which are nested inside others, one of which is a direct sequel to another, and all of which are contributing to the larger serial that is Doctor Who.

if the five episodes previous hadn’t been an extended exploration of the possibility that the Doctor could fail, this story would not have the tone and resonance it does in the first episode.

And at this point, after the last five weeks, there is no real reason why we should expect the Doctor to be able to save the day. Even he seems out of his depth, unaware of the direness of the situation.

He is every bit the ontological force the Doctor is, epic and heroic because he says he is.)

The question isn’t “What happens to the Doctor?” It’s “How are they going to get out of this one?” And in the first minutes of the next episode, we get the answer. They don’t.

It was supposed to be Vicki.

Had they carried through with it and killed Vicki here, it would have been the single cruelest, most cynical moment in Doctor Who history. The plucky joy of British youth, slaughtered. And all of that would have aired right as Vietnam War protests really kicked up in the US, and as the UK careened towards a possible war with Rhodesia. This isn’t just reactionary. It’s savage – a declaration of the fundamental failure of ’60s counterculture made in late 1965, right as it was really starting to kick up to its heyday.

And after the most brutally cruel episode of Doctor Who to date, we get . . . comedy about mice.

Nobody watching this who has been following the serial thinks this is a daft comedy episode. The comedy is bleakly unfunny. This is where Spooner’s genius really shows through, in fact.

It’s easy to mistake this episode as a seventh consecutive episode that doesn’t up to the genius of the fourth episode. But that misses the way that audience expectations are being played with. No. This is bold and clever. The Doctor has, as I said, suffered four consecutive defeats now. And so he’s removed from the picture, and the audience is invited to remember the fact that, flawed as we now see him to be, he’s still far better than the alternatives.

This isn’t suspense. This is tragedy. After four defeats, the Doctor – never quite a hero anyway – seems miles from iconic and mythic. He’s so . . . vulnerable.

It works because we have had the structure of Doctor Who taken apart in front of us over and over again for nearly three months straight.

the Daleks as we know them, the ultimate foe of the Doctor, perfectly matched, each side well aware of the other and full of nothing but hatred.

There is horror and death in the world. Previously, we had thought those things were opposed by the Doctor, and balanced. We thought that he could save us. Now, on Kembel, where the lush jungle has been reduced to a barren desert full of bodies, we know the truth: the Doctor loses sometimes.

The alternative title – The Massacre – does considerably better, but is still a deeply flawed title in that it gives away the end. It would be like renaming The Rescue “The Guy Who’s Disguised As a Monster.”

This is where the Doctor’s string of failures finally resolves as a plotline, leaving him at the lowest we have ever seen him as a character,

Surnames don’t pass matrilineally. Which would mean that if Dodo shares Anne’s surname because she’s a descendent, Anne must have had her out of wedlock. Which is an unusual enough thing that Steven shouldn’t assume it. Unless, of course, he has specific reason to think that Anne might have gotten knocked up . . .

The Massacre, up until Dodo charges in, is a fair contender for Hartnell’s best story.

Here the Doctor is treated as inadequate to a certain type of plot – as if the mercurial trickster figure he represented is just not suitable to big, crashing adventure plots with Dalek armies or massacres, and what the show really needs is a square-jawed action hero like Steven.

The Jules Rimet trophy for the World Cup is stolen, and dug up a week later by a dog named Pickles.

There’s a certain tautology to the logic behind something like this, actually. If you have the insane hubris needed to shoot someone in the head in front of numerous witnesses because you believe yourself to be untouchable, you also have the insane confidence needed to actually be untouchable – at least for a while.

(the pacing of Doctor Who basically accelerates constantly over the years, and frankly, this is almost always a good thing),

Instead we get a remarkably savvy and clever sequence that fools us into thinking that we’re looking at a stock footage elephant (complete with a shot-reverse-shot cut to Dodo’s face that seems designed to hide the lack of a real elephant) only to have the TARDIS crew stride up and touch the elephant.

She’s not an icon of youth culture like Vicki. She’s a vicious condemnation of contemporary youth. She’s an explicit comment that they’re stupid, ignorant, and worthless.

the Toymaker is explicitly dressed and described as a Mandarin. This would be one thing, except the title of the story – The Celestial Toymaker – reiterates this. Celestial does not mean “cosmic” here. It’s old slang for Chinese.

If for some reason you still don’t buy the argument, try Gerry Davis’s novelization of the story, which contains the following sentence: “The Toymaker was lounging in a black Chinese chair behind a lacquered Chinese desk inlaid with mother-of-pearl and scenes of Chinese life, after the style of the Willow pattern.” And later, “The Toymaker stood up, a tall imposing figure, dressed as a Chinese Mandarin with a circular black hat embossed with a heavy gold thread, a large silver red, and blue collar and a heavy, stiffly embroidered black robe encrusted with rubies, emeralds, diamonds and pearls

...more

Stories that are fundamentally about racist ideologies and oppressing people because their culture isn’t as good as yours? Those aren’t Doctor Who stories.

the launch of some pirate radio stations off the coast of Britain,

the story that symbolizes Doctor Who fandom.

in the 1980s, Doctor Who fandom was invented.

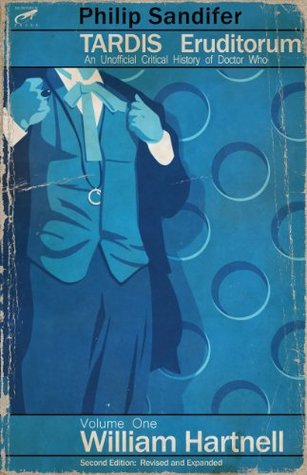

My goal, and I freely admit that it’s made massively easier by the fact that I’m the third one to go over the Hartnell and Troughton era, is to tell the story of how Doctor Who got to where it is today, and to tell this story primarily from the perspective of the episodes themselves, rather than from a production-based perspective.

Purves being a chameleon of an actor, capable of filling in whatever spot is needed in a scene or story. This is particularly useful given that he’s acting alongside the erratic William Hartnell.

The end effect resembles the brutal turn of The Myth Makers, but does something that story did not – sits for a while right on the cusp of comedy and darkness, and lets the viewer twist uncomfortably. And then in the fourth episode, Cotton redoes his Myth Makers trick, and it’s just as good as the first time he collapses a comedy into a tragedy.

Here Doctor Who stakes out the essential difference between itself and Star Trek before Star Trek airs its first episode. At the end of the day, Star Trek is about a man of action on the frontier. And Doctor Who is about a man of words wandering freely through the world.

American cop shows evolve suddenly when the Supreme Court rules in Miranda v. Arizona, and the Vatican finally gets rid of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

Doctor Who monsters in the proper and traditional sense really just haven’t been a part of Doctor Who thus far, leaving the Daleks to be the one thing you can turn to when you need ultimate and inconceivable evil.

Unsurprisingly, when you completely change the medium from “television serial” to “films” without changing the actual content, things go wrong.

this is the first story to abandon individual episode titles in favor of the story getting one over-arching title.

This is a great idea, and one that I think has some real potential for future stories – the idea of people having years to prepare for the Doctor’s arrival because the TARDIS, as a time machine, is visible over time.

(I suppose I should, as part of my continued commitment to helping Americans work through their stages of grief at discovering that there are actually entire facets of foreign cultures that have nothing to do with them, mention that Marmite is a savory, salty, yeast-based spread used in the UK on sandwiches, toast, crackers, and other such things.

passionate love or utter hatred. Thus “Marmite” is, in the vernacular, an adjective describing something that produces extremely polarized views with minimal middle ground.)

Most of the dispute centers on whether or not the book simply goes too far to be a Doctor Who story, and, secondarily, whether it goes too far to be a Hartnell story. Which is to say, the objection is over the fact that Dodo spends an awful lot of this book naked, then also has sex and gets infected with an alien virus that slowly corrupts you.

the idea of regeneration as we think of it today wasn’t invented until the mid-’70s at the earliest.

for whatever reason, fandom is more prone to modify the past based on the future than to reject new stories for contradicting the past

And in the end, one is left between a rock and a hard place. Ultimately, you can either depict the Hartnell era faithfully, or you can fix continuity.

a not entirely uncompelling argument, that the desexualizing of her was what made her not work as a character.

But one thing that does come across is an amazing sense of tone. The Quatermass serials throb with a growing sense of paranoia and panic.