More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

September 22 - October 9, 2020

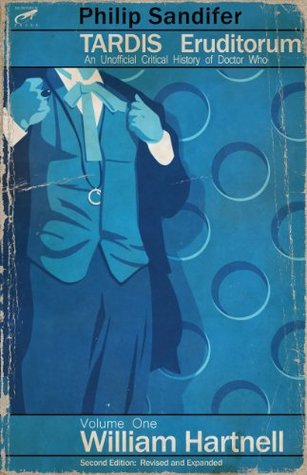

in addition to the meat of the book – entries covering all of the Doctor Who stories produced with William Hartnell as the lead actor – there are four other types of entries.

Time Can Be Rewritten entries.

Pop Between Realities, Home in Time for Tea entries,

You Were Expecting Someone Else entries,

This book version, however, revises and expands every entry, as well as adding several new ones

although I have expanded and revised the essays in this book from their original online versions, I have not attempted to smooth out the developing style of the entries. Much like the show it follows, this project has evolved and grown since its beginning, and I did not wish to alter that.

The Edge of Destruction is based around the paranoia of subversion and the idea of the normal order of things subtly going wrong.

The question stopped being “how will we fight those specific fascists?” and rather became a concern about how fascism started in the first place, starting from the observation that it was something that appeared in “civilized” countries like Germany. This was the era of the Milgram experiments, for instance, and other research into how authoritarianism and control worked.

It’s first and foremost a story about how fascism takes root – of how the institutional structures of authority can be subverted and undermined.

Since 6:30 p.m. the previous day, the BBC has been running news coverage of the assassination of US President John F. Kennedy.

The theme music, ostensibly written by Ron Grainer was, for all practical purposes, realized by Delia Derbyshire, who arranged Grainer’s score by splicing tape together and speeding/slowing a sample of a single note being plucked on a string, white noise, and some testing oscillators.

In a moment of inadvertent brilliance that makes this episode sing nearly fifty years later, she predicts the decimalization of British currency with confidence, although this was merely, at the time, a possible future.

We are, thus far, being pulled along a version of what Tzvetan Todorov calls the fantastic – a sort of tightrope walk between two possibilities. A strange and aberrant event happens, and the story focuses on whether this event is supernatural or the product of a fractured, insane mind. In a Todorov-style approach to the fantastic, the resolution of this ambiguity is delayed until the end, and that’s the primary tension of the story.

Already, in the first episode, Doctor Who is about its own mystery.

We were invited to leave our world via the television. We were, in other words, invited to indulge in escapism.

These three episodes’ most striking feature, in many ways, is Barbara’s nervous breakdown as the four leads wander through a forest following their escape from the Cave of Skulls. The breakdown is stunning both in how viscerally it is shown and in how much it reminds us that Barbara simply does not belong in this setting.

When a box can be bigger on the inside and can smash through the walls of any world, this stops being a meaningful condition. Captivity is merely the possibility of escape. In hindsight, of course, this defines the Doctor.

the possibility of an ur-culture – of some historical civilization from which all contemporary civilizations’ cultural ideas evolved.

This story, at a fundamental level, is about forming the show and deciding who the main character is, with this act, in a move of massively mythic proportions, paralleled with the creation of humanity and the establishment of the direction of human development.

script editor David Whitaker, arguably the single most important figure in the development of Doctor Who,

the Doctor’s description of the TARDIS as being beautiful “in the way that scientific principles efficiently translated into machinery are beautiful.” The sense of beauty in question is a fairly classical one, dating back to Kant and other Enlightenment thinkers who suggested that beauty is based on the appearance of an order or purpose to things, generally an unseen one.

“we are beings programmed to an infinity of surprises.”

That idea of history as a process is, again, crucial. For Whitaker, what matters about time is that it is a process of change. Changing history is a silly idea because history is itself change.

a show based around the passive acceptance of a fixed world of wonder would never have lasted as long as one about the continual embracing of change. In the end, whatever The Masters of Luxor’s virtues, David Whitaker was, on the big issues, right.

These are stories that still, at their heart, believe in the basic value of British culture and, more to the point, that the rest of the world would be a lot better off if they’d just let some intelligent and competent British people come by and sort everything out for them.

World War II images – retellings of the basic parable that appeasement doesn’t work, that pacifism is noble but fatally flawed, and that true evil must be fought.

When we get to The Keys of Marinus we’ll suggest that Nation’s plotting oddly anticipates video games,

In this regard, the history of Doctor Who can be read as a steady move away from the approach of Dan Dare, which also helps explain how Terry Nation goes rather quickly from being the defining writer of the series to being an odd throwback whose stories feel desperately out of pace with the times.

That’s the central alchemy of these earliest Dalek stories – the sense of a popular science fiction icon being surpassed.

Terry Nation, for all his influence at the start of Doctor Who, is relevant primarily as a passing of the guard – the writer who best channeled the approach that Doctor Who defined itself as breaking away from.

Johnson declares a war on poverty, John Glenn leaves the space program to become a politician, and we start to figure out that smoking is bad for you.

Everything changes, yes, but (and not for the first time) nobody notices it happen.

Susan, emerging from the TARDIS, encounters a Thal. The camera holds on Susan as she reacts to it, finally saying that she had expected the Thals to be disfigured, but then uttering: “You’re perfect.” With that, the camera cuts to a strapping blonde Adonis of a Thal, indicating the definition of perfection. The degree to which this definition is Aryan is all the more chilling given that Carole Ann Ford, who plays Susan, is Jewish.

Doctor Who acquires one of its fundamental dualisms: people and monsters. But this should make us uncomfortable. Monsters are monsters because they don’t look like us. For all the importance monsters have to Doctor Who – and the monsters are a genuinely important part of the show – there is something ugly about the idea of them. What is interesting is that the fundamental evil of the Daleks is explained by their hatred for things that are not like them.

To give an idea of how entrenched racism was in the US, Senator Robert Byrd, who did not leave the Senate until his death in 2010, joined a filibuster led by President Pro Tempore of the Senate, Richard Russell, who declared that “We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would have a tendency to bring about social equality.”

As this story ends, the Doctor, with obvious glee, provides the Thals with guidance on how to start a new civilization. He declines to stay – he is too old to be a pioneer, though once, he says, he was. But his love of creating a situation like this is obvious. It is the first time since Ian and Barbara intruded on his life that he appears happy. Here, for the first time, he is truly learning to be the Doctor.

Whitaker is responsible for introducing a set of alchemical themes to Doctor Who that actively render the show mystical in its implications.

the episode improbably picks up with an absolutely insane and thoroughly chilling scene in which Susan deliriously stabs a whole lot of things with scissors.

Doctor Who’s canon, you see, is wholly additive, with new things just sort of being grafted on to the knobby bits as time goes on. Basically, it’s a giant narrative Katamari.

I mean, that, right there, is the end of any claims that Doctor Who might somehow, if you think about it long enough, make sense. No. Doctor Who might somehow, if you think about it long enough, drive you very productively mad.

Which is, in many ways, the full establishment of the TARDIS – on the one hand, it is a magical box that can think and communicate with its inhabitants. On the other hand, it can accidentally have a spring get stuck and proceed to nearly explode.

the TARDIS functions along entirely symbolic and thematic terms.

The TARDIS communicates by analogy; its danger comes as much from a radical contrast of the forces of creation and destruction as from any sensible concept.

But it’s the story of a time-traveler, and that shows. It is a story that goes back and revises itself so that early episodes are at times best read in terms of later developments

Doctor Who has always been a show more about the question “how are they going to get out of this one” than “are they going to get out of this one.”

The Beatles have the number one single with “Can’t Buy Me Love.” In the next six weeks, we will discover why the Beatles are unable to buy love – namely that, as Peter & Gordon observe, this is “A World Without Love,” making the Searchers’ admonition “Don’t Throw Your Love Away” sound advice.

The Keys of Marinus, a serial which, in hindsight, is plotted like a video game.

the development of BASIC would be integral in the nascent hacking movement of the 1970s that would eventually translate into the video game industry

a planet with a glass beach and an acid sea, monsters in fantastic rubber gimp suits called the Voord, mind-controlling brains with eyestalks, killer vegetables that psychically scream, snow wolves, robotic knights with plastic capes, and a courtroom drama that out-hams Phoenix Wright. All in just under two and a half hours.

the sheer pluck of vintage ’60s sci-fi has found its ultimate expression and final form – a show where mad ideas can be stacked next to each other and swapped about at high speed.