More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I tried to impose order on the inevitable chaos that a death leaves in its wake. There is chaos left behind even when the person who is gone was a meticulous genius, like you. And you were a genius, or as close as I’ll ever come to knowing one, the most fastidiously brilliant man I have ever known.

Death, it turns out, to those left behind, is an activity centered around the cataloging and dispersal of material objects.

I am a thirty-four-year-old literary academic with inherited wealth and no one to share it with.

I cannot help but imagine the forecast that long-discarded 8 Ball might give me now, if I rolled it over and asked what tomorrow holds: OUTLOOK NOT SO GOOD.

My father never even visited the Caribbean. I wanted a sign and I got one.

It is always dangerous to look too hard into the lives of those you love and respect more than anything.

“Anderssen’s Opening is a chess move. A challenge. A very strong, very rare opening move. Adolf Anderssen beat Paul Morphy with it in the 1800s. Anderssen’s Opening was sneaky. Is sneaky. You move your least important pawn one square forward and you wait to see what the opponent does next. It’s a non-move, a taunt almost. You put the ball in their court—and then you watch and wait to see what they do next.”

And yet I see as plain as day that the house in front of me is entirely my father. The clarity of the lines, the purpose, the simplicity and synergy with the natural world around it. An emotion I had not anticipated shifts deep inside me: loss, profound loss. I feel my eyes fill and I quickly tear them from the building.

Maybe he built this house for me. I let my thoughts roll and revel for a moment before shaking myself back to reality. He did not build this house for me; it was finished long ago and I was never made aware of it. My eyes prickle again, because I am tired, and I miss him, and I want to lie down.

“Bathsheba, play ‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.’ ” I feel my eyebrows shoot up. Bathsheba was our cat when I was growing up. And biblically, of course, the lover of King David, who, having seen her bathe, lusted after her, killed her husband, and married her. Then God struck down their firstborn as a kind of bizarre punishment. The sins of the father and all that. I just liked the name.

Then my eye falls to a small ebony sculpture, a woman about to be engulfed by some unseen force, on the table beneath it. The figure’s posture is tensed and ready for a wave that will never come. The air-conditioning catches on something hidden beneath it. An edge of white paper, flapping every so often as the fan’s flow hits it. I walk over, tilt the sculpture, and pull the paper out from beneath. I unfold its thin page. It appears to be some kind of invoice for electrical work undertaken. A small pencil-filled docket.

No one owes all of themselves to anyone else. We are all individuals, and what we give of ourselves, we must choose to give freely.

But parents hide a lot of the world from their children, especially if they love them.

Silence sets the imagination on fire. And my imagination is primed with fears, death high up there, death front and center of everything right now. And when you are alone there’s a lot to be afraid of: intruders, accidents, or perhaps, worst of all, the slow unspooling of your own lonely mind.

“Thank you for loving me every day of my life, Dad.” And the last thing he said to me: “It was the simplest, best thing I ever did.” And

A note is flapping in the warm breeze on the wall, a rock holding it in place. I down a massive gulp of coffee and head over to get a better look. As I get closer my pace slows, the words coming into focus. It is definitely not a note from James. I stop abruptly as I read it, a warning, or a threat, roughly penned in Sharpie. You need to leave. Now.

the memory of only the three of them surviving. The three of them, alone, made it through with the forest dirt and the shiver of what it took to do so.

No, it is instead the sense that she was there, alone, and not in the normal sense that one might be alone, like he is, but in the sense that she was clearly waiting for something. Waiting for something to happen. And that room, the room she had been told not to enter; he cannot stop thinking of that strange white room.

But the thought vaguely occurs to Joon-gi that they might somehow be keeping her in rather than keeping everyone else out.

The discovery of the existence of more house beneath Anderssen’s Opening is deeply unsettling in itself, but the thing my thoughts snag on more is who on earth has been pretending to be me for months.

Back at the house, when I make my way cautiously up to the top of the stone steps, body pounding with exertion and tiredness, it takes me a second to notice that something isn’t quite right. Plastered across the front door is another note. It is taped to the glass, and as I approach, I read the words on it. Do not go down there

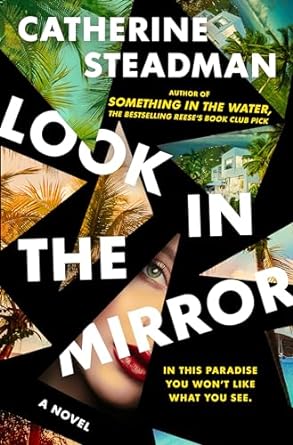

I flip the note over but the back is blank. I reread its scratchy words: Look in the mirror

But he is not accepting it, because it’s incredibly strange. For the property to go from high security to no security in just four days is notable. He distinctly recalls the woman saying she would be remaining here for the next ten days.

He cannot possibly know that he will only remain conscious for another ten minutes.

Looking back at me I see now what I perhaps couldn’t see before my father died; I see the truth, or as close to it as I have ever gotten. I see a scared woman in her thirties with no family, no friends, a dead-end job, and nobody to come home to.

All thoughts put on hold as a woman in a long flowing black dress emerges through one of the terrace doors. She is beautiful, but she isn’t Nina.

Her questions hang awkward in the air. She could of course answer them herself. Why would anybody do something like this? Because they can, because awful, evil people have always existed and sometimes you can’t tell they’re awful and sometimes those people turn out to be someone’s lovely loving clever cuddly dad.

All the non-consensual participants, like Maria and the ones before her, were chosen this way. Each person chosen for the house was the sole remaining next of kin of a terminally ill relative.

“And how are the super-rich these days?” he asked with a sly smile. “As strange and hard to please as ever, I imagine,” she answered. “Yes, as it ever was. Well, rather you than me, I know that much.”

He must not have known what the house had become. He must not have realized. She sailed as close to the wind of truth as she could get away with, because she knew he would sense a lie if it was offered.

Lucinda stood and headed for his desk. She slipped the small desk clock, and a Montblanc pen, into her handbag. As the kettle flared up again in the kitchen, she gently tugged his central desk drawer open and slid out a thin copy of The Waste Land from its dark interior along with a small Moleskine journal.

“Take care, Lucinda,” he told her, his hand still shaking hers. “If you ever run into my daughter, keep an eye out for her, would you. You seem like a nice girl.” He released her with a warm smile and then chuckled lightheartedly. “You’ve just fallen in with the wrong crowd, I think. But money makes fools of us all. Who am I to judge.”

She doesn’t doubt her father changed that woman from the inside out—good people can do that, a little kindness can do that; it has that power.

He hasn’t stood her up, he hasn’t chickened out; Joon-gi has made it here after all.