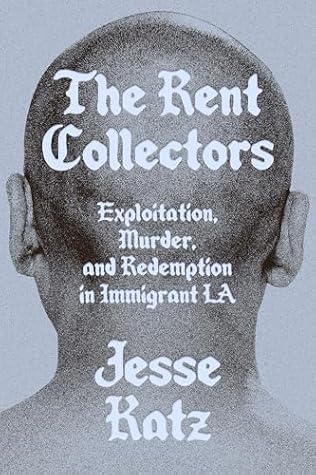

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Jesse Katz

Read between

January 1 - January 5, 2025

On the cusp of adolescence, Reyna felt both rejected and besieged, a salvadoreña Cinderella, saddled with endless chores and babysitting duties.

18th Street was likely the largest gang in the United States, if not beyond. It grew by breaking the mold of traditional, multigenerational Mexican American gangs, which tended to adhere to a strict racial caste system and century-old turf lines.

The US Department of Justice threatened to sue the LAPD for “a pattern or practice” of civil rights abuses, resulting in a consent decree that placed the police under federal oversight. In the end, two dozen officers were suspended, fired, or forced into retirement. More than a hundred criminal convictions were overturned. And to settle the wave of lawsuits, the city paid out more than $125 million.

Compared to the Crips and the Bloods, or even MS-13, the infamy of 18th Street never quite penetrated popular culture, perhaps because the name sounded unromantic—mathematical.

“You have to lose your embarrassment,” she says. “With embarrassment, you’re not going to eat.”

Across LA some fifty thousand vendors, most undocumented, were performing a version of the same venture, generating a half-billion dollars in annual street sales.

in 1999, MacArthur Park welcomed the city’s only legal vending district—a corner of the park grounds at Seventh and Alvarado.

The RICO Act gives the feds a powerful penalty enhancer, allowing them to piece together seemingly unrelated crimes that alone might not have triggered long sentences and to prosecute them under the banner of a broad conspiracy.

As offensive as killing a child was to every legal and moral principle on this planet, it constituted a special atrocity within the gang world, something akin to a war crime. There was a code, albeit one that allowed for all manner of carnage—a line that still determined what was off-limits and preserved some frayed vestige of honor.

In 1986, a twenty-year-old San Diego State University student named Cara Knott was pulled over by a California Highway Patrol officer on a dark, isolated off-ramp along Interstate 15. It was the same spot he’d chosen for making creepy overtures to other women drivers. When she resisted his advances, the officer grew enraged, strangling her with a rope and heaving her body off an abandoned bridge. Cara Knott had been Dave Holmes’s babysitter.

The 3000 Boys were among nearly a dozen secret cliques across the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department whose decades of brutality, inside the jails and on the streets, have cost taxpayers upward of $55 million in abuse payouts.

In 2012, the year that Paul Keenan’s case against the Columbia Lil Cycos went to trial, more than 80,000 criminal defendants were charged in US district courts. Fewer than 2,500 tested the sufficiency of the government’s case at trial. And, of those, only 355 emerged with not-guilty verdicts.

The new law, which took effect in 2016, changed life for sixteen thousand California inmates, Giovanni included. It entitled him to a youth offender parole hearing in his fifteenth year of incarceration, and it required that the parole board, when evaluating his suitability for release, consider Giovanni’s diminished culpability—the “hallmarks of youth”—and any increased maturity.

Covid preyed on the inmate population, infecting 90,000 incarcerated people across the state and killing 260, including 21 of Giovanni’s neighbors. The steady bleat of alarms and sirens unnerved

California’s Prison Industrial Authority enlists some seven thousand inmates across the state to help run a hundred different kinds of commercial operations, from manufacturing prison clothes and stamping license plates to harvesting fresh eggs and running an optical lab.

The rate for Giovanni increased from 15 to 33 percent, meaning that for every two days served, he’d get credit for three. Instead of thirty years left on his sentence, he now had twenty.