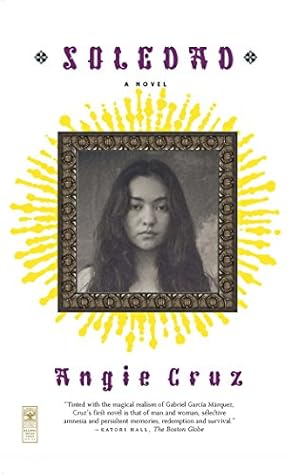

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

You don’t realize how hard it is to take care of my boy. He likes his food just so. Nothing too wet or mixed up. Likes it to be served separated and hot, otherwise my Victor won’t eat it, she says, messing up Victor’s hair.

Instructing the future wife or claiming some stake as to how much she knows about her son that another woman does not

He didn’t even know how to describe what happened to Olivia. Everybody in the family has their own theories but he still does not understand what makes her that way, what makes her watch him when he’s sleeping sometimes. How he feels uncomfortable seeing her naked. He’s her sister. Breasts don’t belong on sisters.

He wants to tell her that his family is being much louder than usual, that he’s afraid she might not see him in the same way. He wants to tell her he hates it when they treat him like a child. She might learn how much he depends on them, how one day he might depend on her that way.

Recognizes how easy he has it with women taking care of him and prefers it that way even though it is embarrassing to admit

Victor tries to remember what it was like when he was a shoeless kid, strong enough to climb trees. Now his legs feel heavy. He remembers Doña Sosa much younger, thinner. How the years seem to pass and blend and wonders what Isabel might look like in twenty-something years.

Red for heat, asking the spirits to make Soledad perpetually sweat. Blue for her heart to freeze and no guy will ever like her. Green for money so she can take flight, and leave us all for good. Yellow for extra rotting inside, for guilt buildup, for her skin to turn rough and yellow like the skin of lemons. Purple for bad dreams, nightmares that will deprive her from sleep.

Sorry for what, for inviting the devils into this house? They were the ones that put those stupid machines inside of him. All those machines, to help him breathe and make his heart beat, you know what they did? They made him lazy, Soledad. Don’t you see? He had no reason to work at living no more.

on. It was rare to have a man like your father pick a woman like me as a wife. I mean, we were the kind that had a few too many feet in a Haitian kitchen. But it was as if we had no choice. He asked me if I would go with him and all I had to do was look at my father and find out if I was going or not.

wonders if it ever works. It didn’t work for Gorda and Raful, or Olivia and Manolo. Or even his parents. His poor mother taking care of his father who hasn’t been able to be a husband for years. Now that he’s dead she’s left alone. Forty-five years with one person.

It’s not Manolo, it’s men. You might as well kill them all. Are you so different? I’d never hit a woman, Victor said again and again. But you drink and cheat. That’s bad enough. And so did his father. His father, who wouldn’t hurt a fly, took away ten years from his mother’s life, who had to work, and take care of him because he couldn’t do anything for himself. Victor thinks about his father and how he doesn’t want to end up like him.

That was before he became a drunk. That was before he took a nap with me and Flaca on a Saturday afternoon. He was supposed to be watching over us when my mother went food shopping. That day he squeezed himself in between us. I pretended to sleep, kept my eyes closed, as he reached over me, his arms heavy on my side. His

Querida, all this drama. What kind of fantasy world do you live in? What is a father anyway? A role. That’s all. A parent is someone who makes sure you’re fed, and have a place to live, who loves you until the day you die. You have that and more. You have all of us, mi’jita. You don’t need any of these men to be your fathers.

Power of a parent, particularly a father, is not as important as Soledad believes--according to Gorda.

Watch one day, Flaca, if I ever win the Lotto I would go back home and buy some land in D.R. and build a house with a huge garden, like nobody in San Pedro de Macorís has ever seen before. I would get me some of those really nice wooden rocking chairs and put them in the backyard. I would get a fountain. A little boy peeing. I always loved those. And the house would have many rooms with each person’s name on each door so everyone in this family always knows they have a place they could go that is completely theirs. I would even build a room for your crazy mother. She would like that. I know

...more

Ay Flaca, my baby left me and I didn’t do a damn thing to stop her. I just let her go. But Soledad will be back. There’s no way she gonna survive in this crazy world all alone like that. Everybody needs family.

Belief in the essential survival through family. Her experience in Puerto Plata probably confirmed that idea

Flaca’s too young to see anything. That girl believes the world revolves around her and her needs. She doesn’t imagine other people’s pain. Not yet anyway. Besides, people see what they want to see.

Gorda, all my life I’ve wondered why I am the way I am. I never wanted to be like my father, he was such a dick, and Mami always looked so unhappy, hiding, and pretending to be so strong to save me from her pain. It just made it worse. Every day, she pushed me farther away from her, until she didn’t have to push anymore. I just left. But this is my chance to give me and her another way to live free from all this crap.

The thought of going to D.R. all by myself is terrifying. With my mother even worse. I remember the way people ask for so much. My mother’s aunts, uncles, and cousins asking for mandaos. Just send a small TV, that’s all I ever wanted in the world. They will want my jewelry, my clothes and take them off my back. And of course I will have to give it to them because you can’t say no to family. They will want me to watch them kill the goat in the backyard, or they will break a chicken’s neck so I can have it for dinner. Because I’m a gringa, they will fill me up with refresco rojo and not let me

...more

Expectations from family in DR are stressful because of their living conditions, demands, and sacrifices

My mother was always filled with if onlys. If only I never married your father, if only I never came to this country, if only . . . And now I wonder if only I never went away like I did, had more patience, not gotten so angry at her. I was always so angry. If only I had really listened, given up on the idea of what a mother should be like and seen her as a human being with her own needs, desires, nightmares and dreams.

They’re so happy to see us I can’t understand a word they’re saying. Talking so fast, grabbing my bags, pushing me toward the car.

It is clear that my grandmother’s home in Washington Heights is temporary, until they make enough money to return home. Victor and Gorda also call this place home. In the end they are born and want to die on the island they think of as home. Home, rice and beans, apagones, plátanos, mango trees, día de los muertos, strikes, warm beach water, malecón, never having an election that doesn’t get recounted home . . . In New York, they don’t live, they work, until we go home. My mother always told me that home is a place of rest, a place to live.

that’s what familia is for. And when Soledad agrees with Cristina I get angry at her and everybody all over again for abandoning me when I needed them most.

When I was too young to fear getting raped, or hurt or lost. Like my cousin Lolita, who at fourteen wandered off following a crab and was raped by a man who agreed to marry her so he wouldn’t have to go to jail. And her family allowed it to save her virtue.

start to run until I realize no one’s running after me, only the memories. I’m tired of being afraid of hiding inside an apartment with gates so the burglars won’t come in. I’m tired of running, I’m tired of letting what other people think of me, or will discover about me, control my life. I’m tired.

She never wanted my help. My heart would break, thinking how already as a little girl she didn’t need me when I needed her so much. And now she holds my hand as we walk through the winding steps,