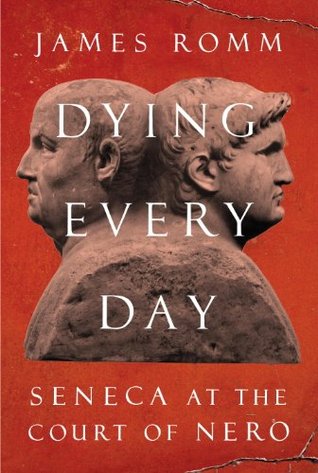

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

James Romm

Read between

February 7 - February 15, 2025

I was better off hidden away, far from the crimes wrought by envy, shunted off from it all, on the cliffs of the Corsican sea.… How glad I was there, my eyes on Nature’s masterwork— the sky, and the sacred paths of the sun, the cosmos’ motions, the allotments of night and day, the sphere of the Moon, that glory of upper air, spreading its light to a ring of unanchored stars.

Seneca never commented, in any of his extant works, on whether he regretted his departure from Corsica, by far the most consequential of the many turns his life took. Some later claimed that he hoped to go to Athens, not Rome, when he left, to study the works of great Greek thinkers in the city where they had lived. But the claim might well have arisen as an effort at image repair. There were many supporters of Seneca, including Octavia’s author, who portrayed him as what he strove to be—a moral philosopher of the Stoic school—and sought to counter the charges, brought by others, that he was a

...more

In his writings, Seneca praised Sextius’ choice, to practice philosophy and forsake politics, but in his own career, he did not follow it. Somehow, by a thought process he never revealed to his readers, Seneca decided, in his thirties, to pursue both paths. Still practicing ascetic habits that he learned from Attalus—sleeping only on hard pillows, and avoiding mushrooms and oysters, Rome’s favorite delicacies—and studying natural phenomena, he nonetheless embarked on the cursus honorum that led, ladderlike, to ever higher offices. In his late thirties, after a sojourn in Egypt with a powerful

...more

see your soul shrinks back from public office and disdains all ambition, and desires only one thing: to desire nothing,” the crusty old man of letters wrote, urging Mela toward his own specialty, the study of rhetoric. “You were always more intelligent than your brothers.… They are all about ambition and are now preparing themselves for the Forum and for political office. In those pursuits,” he remarked, as though issuing a warning, “the things one hopes for are also the things one must fear.”

Agrippina’s brother did not care for Seneca, nor for the epigrammatic style in which he spoke. “Sand without lime,” Caligula called those words, drawing an analogy from the building trade, where sand and lime were mixed to make mortar. Seneca’s speeches, to Caligula, seemed to lack solidity—ear-catching phrases strung together without binder to firm them up. (That critique has been repeated, in various forms, ever since. Lord Macaulay echoed it in the 1830s when he wrote: “There is hardly a sentence [in Seneca] which might not be quoted; but to read him straightforward is like dining on

...more

Over seven decades, the Senate had tried to assert its ancient prerogatives. But the princeps always had the final say, thanks to his personal army corps, the Praetorian Guard. These elite soldiers, encamped at the northeastern edge of the city, alone had the right to bear arms within Rome’s boundaries. Each emperor had been careful to ensure that these troops, and in particular their prefects or commanding officers, were well fed, well paid, and loyal to his cause. Though it was bad taste for a princeps to deploy Praetorians against the Senate, all parties were certain that, if so ordered,

...more

No one quite knows how the downturn began, but Seneca, an eyewitness, attests to the terrifying depths it reached. Caligula stalks through Seneca’s later writings like a monster in recurring nightmares, arresting, torturing, and killing senators, or raping their wives for sport and then taunting them with salacious descriptions of the encounters. “It seems that Nature produced him as an experiment, to show what absolute vice could accomplish when paired with absolute power,” Seneca said of Caligula’s madness.

Consolation to Marcia, written about A.D. 40, takes the form of a letter addressed to a mother grieving for a dead son, but it was meant to be read widely. Seneca would play the same rhetorical trick his entire life, allowing his readers to listen in on what seemed to be an intimate exchange. His addressee was often a family member—his elder brother Novatus on several occasions—or a close friend. In this case, Marcia, a middle-aged woman of senatorial rank, was not connected with Seneca in any recoverable way. She was, however, the daughter of a man who had been persecuted by Sejanus,

...more

Seneca does not deny Marcia the right to grieve, for that would be cold—and coldness was often charged against the Stoics, as he was well aware. Seneca’s version of Stoicism was softer, more adaptable to human frailties. Mourning is natural for a bereft parent, Seneca allows, but Marcia’s grief has surpassed the bounds of Nature. Nature, for him as for all Stoics, was the master guide and template; it was allied with Reason and with God. Indeed these three terms, for Stoics, were close to synonymous. Marcia’s grief, for Seneca, exemplifies a universal human blindness. We assume that we own

...more

Is life on a battlefield, or on death row, worth living? Seneca seems to be of two minds. At one point, he extols the beauty of the world, the joys that outweigh all suffering. At another, he reckons up the pains of mortal life and claims that, were we offered it as a gift instead of being thrust into it, we would decline. In either case, life, properly regarded, is only a journey toward death. We wrongly say that the old and sick are “dying,” when infants and youths are doing so just as certainly. We are dying every day, all of us.

To finish the job early on, as Marcia’s son did, is a ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Seneca aims, as he would do throughout the next quarter-century, to change the way humanity thinks about our greatest crisis, death.

As the fatal strokes fell, they changed forever the unwritten definition of the principate. Caligula’s experiment in absolute power had proved that there was, finally, a check. The Praetorians had imposed it. And in the hours that followed the murder, they also seized a central role in the question of succession. While the Senate dithered vaguely over a hoped-for return of the republic, soldiers collected Caligula’s sickly paternal uncle, Claudius—found trembling behind a curtain, according to legend, though more likely well briefed on what was to happen—and brought him to the Praetorian camp,

...more

The harrowing stories of De Ira (“On Anger”), probably written soon after Caligula’s fall, show the young senator reckoning up the spiritual cost of despotism: the psychic wounds suffered by those forced to capitulate. It was the defining problem of Seneca’s age, and he was to grapple with it as no one else did, both in his writings and in his own life. De Ira is Seneca’s first in a string of treatises, each dealing with a single ethical topic announced in the title (De Clementia or “On Mercy,” De Brevitate Vitae or “On the Shortness of Life,” and so on). Anger leads the series of topics

...more

Not only in Rome, but everywhere and in all times, good men have knuckled under to despots.

De Ira teaches its readers to avoid anger by disregarding injuries. But the cases of Harpagus and Pastor test the limits of this doctrine. It is one thing for a great Stoic to ignore a man who jostled him in the public bath, or even one who spat in his face (two other tales told in De Ira). To accept the murder of one’s children goes beyond anger management, into the realm of moral self-annihilation. Yet Seneca suggests, initially, that this is indeed what his teaching requires. “That’s how one eats and drinks at the tables of kings, and that’s how one replies,” he comments on the tale of

...more

Stoics had long considered suicide to be a remedy for inescapable ills, including abuse by a cruel despot. But what had been a minor topic among the Greek Stoics became all too central in Rome in the age of the Caesars. Indeed, for Seneca, it became a kind of fixation. In writings throughout his career, he recurs again and again to agonizing questions of how, why, whether, and when to take one’s own life. Later ages decided he had been aptly named, deriving Seneca from the Latin phrase se necare, “to kill oneself.”

The gruesome self-disemboweling came to be seen as an exemplary act of lived philosophy. It showed a heroic devotion to autonomy—the personal freedom that Caesar’s victory had threatened—and a superhuman defiance of pain and fear. As the Caesarean system took hold, Cato’s suicide took on new meaning to those who mourned loss of liberty, shining ever brighter as a moral exemplum. In Seneca’s works, it glows incandescent—as does nearly everything Cato did or said. But political suicide in Seneca’s day was a different gesture than it was in Cato’s. Often it signaled acquiescence to autocracy

...more

The system had become formalized by the time of Caligula, who kept two notebooks of enemies’ names, titled “Sword” and “Dagger.” The first listed those whom the soldiers would behead; those on the second would open their own veins (an operation requiring a much shorter blade). The state had a vital interest in keeping these categories distinct. In at least one case, a man attempting suicide and on the point of succeeding was rushed as he expired to a place of execution. He managed to die en route, cheating the princeps of an estate. Even as their lifeblood ebbed away, political suicides knew

...more

By his day, suicide had come to signify, for aristocratic victims of the emperors, an inability to fight back; the best one could hope for was to embarrass the princeps by a highly public exit.

In De Ira, accordingly, Seneca portrays suicide as an escape route, a way to gain release from the power of kings. What he doesn’t acknowledge, or isn’t aware of, is that suicide can also be a means of fighting back—even though an example was right before his eyes.

The principate was not a monarchy—Rome had rejected that institution five centuries earlier and still officially reviled it—and so had no guidelines for succession. Nonetheless, a blood link to the holy figure of Augustus conferred innate legitimacy. The reign of Augustus’ successor, his stepson Tiberius, had taken the throne outside that bloodline, while that of Caligula had restored it. With the accession of Claudius—who had not even been adopted by his predecessor, as Tiberius was adopted by Augustus—the office of princeps and the “royal” line had again parted ways, a situation that made

...more

“It is the mind that makes us rich,” he told his mother, to dissuade her from mourning his fate. “The mind enjoys a wealth of its own goods, even in the harshest wilderness, so long as it finds what is enough to keep the body alive.” These words might have been written by Thoreau at Walden Pond, although the terms of Seneca’s exile, which allowed him to keep half his estate, gave him access to ready cash. Corsica, as Seneca conjured it in Consolation to Helvia, was an ideal proving ground for the main Stoic tenet: true happiness comes from Reason, a force allied with Nature and with God. All

...more

Why would any devoted Stoic, having found a paradise of Reason beneath a benign firmament, ever return to the cesspool called Rome? The question goes to the heart of the enigma of Seneca’s life. Seneca’s friends and supporters recognized its importance, for they suggested, in the play Octavia and elsewhere, that his return to Rome from Corsica, eight years after leaving the city, was not voluntary. But Seneca gives them the lie in his own writings. In a second open letter from exile, probably written a year or two after the first, Seneca showed, obliquely but urgently, that he was desperate to

...more

Seneca’s letter to Polybius repeats Stoic remedies for grief that he earlier preached to Marcia. But he has added a new one, tailored to the needs of a courtier. “When you wish to forget all your cares, think of Caesar,” he wrote, referring to Claudius. “So long as he is safe, your family is well and you are in no way harmed.… He is your everything.” A courtier’s joy flows from the princeps he serves; and this particular princeps, Seneca goes on to say, brings joy supreme. “Whenever tears well up in your eyes, turn them toward Caesar; they will be dried by the sight of his greatest, most

...more

Some said the world would end in fire; some said, in water. Seneca’s Stoic masters had taught that fire would bring to a close the present age of the world. Tongues of flame arising from the outer cosmos would rise in intensity until they scorched away all living things and all traces of humanity. Then, like a phoenix rising from its predecessor’s ashes, life, and civilization, would begin again. Seneca adapted the cyclical scheme in Consolation to Marcia by making water, not fire, the agent of destruction. This made the apocalypse more imminent, for the fatal waters could arise from beneath

...more

To Seneca, who lived in a city that had reached unimagined levels of sophistication, that terminus seemed not far off. Wealthy Romans could not only obtain snow and ice from mountain summits to cool their drinks and bathing pools—a practice Seneca deplored—they could dine on rare birds and shellfish and watch the combats of wild animals brought from all corners of the world. The reach and scope of the empire in the mid-first century A.D., its ability even to cross the English Channel and seize territory beyond, struck Seneca’s mind not merely as a triumph of power and technology but as a sign

...more

age will come, in later years, when Ocean will loose the bonds of things, and earth’s great breadth will stand revealed; Tethys will disclose new worlds, and Thule no longer be last among lands.

It is not known when Seneca wrote Medea or any of his tragedies for that matter. But it’s a fair guess that Claudius’ invasion of Britain was much on his mind at the time. Romans celebrated the feat, and Claudius himself led a triumphal procession of conquered Britons through the capital’s streets. In Seneca’s view, however—a view that perhaps anticipates the thinking of modern environmentalists—the ceaseless advance of empire would turn the cosmos itself into an enemy. When everyone could go everywhere, when no boundaries remained intact, total collapse might not be far off.

For Seneca to express such dour views, even from exile on Corsica, would no doubt have been risky. Tragic dramas, which tended to center around arrogant or deluded monarchs, were always risky under the principate; Tiberius had once ordered a playwright executed for a single line about the blind folly of kings. It is not clear that Seneca ever had his plays performed or even allowed them out of his house. There is no evidence they were known in his day, and Seneca himself says nothing about them elsewhere in his writings. Perhaps they were private documents, shared with a trusted few—a way to

...more

To Roman readers in A.D. 49, Phaedra would have raised uncomfortable associations. They saw Agrippina as a tempestuous, controlling, and highly sexual woman, not unlike Seneca’s heroine. She had already been accused of incest with both Caligula and her brother-in-law Lepidus; she was now incestuously married to her uncle Claudius. And she had become a stepmother. The chances that she would be a wicked one, given that she had a son of her own to protect, seemed high. Seneca’s Phaedra would have been perilous for its author indeed, if released against this backdrop. Was palace life imitating

...more

It was contrary to Roman law for a man with a living son to adopt another. Such an arrangement would clearly threaten the rights of his natural offspring. But Nature had already been superseded by Law when the Senate voted that Claudius could marry his niece. On February 25, A.D. 50, the senators passed a special act of adoption requested by the princeps himself. Claudius gained a new son and gave him a new name: Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus, or as he soon became known, Nero.

Nero had not only purity of blood but seniority in his corner. He would reach all the stages of political maturity more than three years before Britannicus: at fourteen, the donning of the toga virilis, the wool tunic signifying adulthood and responsibility; at twenty, the minimum age for officeholding; at twenty-five, the right to sit in the Senate. It was not clear how many of these milestones a youth had to pass to qualify for the principate. But Nero was almost sure to pass more of them, during Claudius’ lifetime, than his stepbrother.

As a consul-to-be, Nero was entitled to exercise proconsular power—like a modern teenager driving with a learner’s permit—and to wear special clothing and insignia. His new stature was therefore highly visible in the streets of Rome. At a special round of games put on to mark his elevation, he was presented to the crowds wearing his new markers of high office, while Britannicus appeared beside him in the simple cloak of a boy. The contrast was a humiliation for Britannicus and a clear indication of the new order of things.

Seneca had no choice but to take Nero’s side, despite the fact that in Consolation to Polybius, sent from Corsica, he had effused over the young Britannicus. “Let Claudius confirm his son, with lasting faith, as steersman of the Roman empire,” he had written. But that was before a second son had appeared on the scene, and before that boy’s mother had become his patroness. Now Rome needed clarity and decisiveness about the way forward.

Seneca never commented, in any extant work, on the palace rivalry, but a line he quoted from Vergil seems to address it indirectly. In A.D. 54, when Nero was already on the throne but Britannicus’ claim was still supported by many, Seneca imagined one of the Fates saying: Death to the worse; let the better one rule in the empty throne room. The verse comes from Vergil’s Georgics, and gives instructions for managing a hive that has two “king” bees (Romans thought hive leaders were male, not female). Seneca quoted it in another context, but he must have been aware, given the

...more

Since Nero was now, in law, Claudius’ son, Octavia had to become some other man’s daughter; even a regime founded on a union of uncle and niece could not sanction that of brother and sister. Octavia was adopted by a patrician family so that she might marry insitivus Nero, “grafted-on Nero,” the sneering title she gives her husband in the play Octavia.

Agrippina had gotten all that she sought. She had elevated Nero to presumptive heir and greatly diminished Britannicus. Her own stature had risen along with her son’s. Shortly after his transformation from Domitius to Nero, she had received a new name of her own, the honorific title Augusta. Only the most revered imperial women had borne this title before her, and only as widows or mothers of emperors. Agrippina was the first to claim it as wife, and the shift betokened a new definition of the role. An Augusta was now—or so Agrippina hoped—the female counterpart of a Caesar, entitled to sit

...more

Agrippina’s paternity gave her enormous credit with the army. So did her name—a feminine refashioning of that of her grandfather, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, the general responsible for Augustus’ greatest victories. Alert to the value of these assets, Agrippina found an ingenious way to advertise them to the world. Agrippa had founded a town in Germany as a haven for the Ubii, a tribe he had brought under Roman dominion. His son, Germanicus, later made it his base of operations. Agrippina herself had been born there, during her father’s glorious campaigns. This place, as yet only a regional

...more

Agrippina had gained power unprecedented for her gender, greater even than Messalina’s, and she was even better than her predecessor at putting it to use. A familiar pattern emerged, in which enemies of the empress—in particular, attractive, marriageable women—suddenly found themselves labeled enemies of the state.

Elevating the lowborn or fallen, thereby making them dependent and loyal, was a time-honored strategy for Roman rulers, as it has been for autocrats everywhere. Agrippina had already used it to great effect with her recruitment of Seneca, whom, like Pallas, she had gotten appointed praetor. Their shared reliance on Agrippina gave Seneca and Pallas, the Roman moral philosopher and the Greek palace lackey, something in common. Both men, moreover, had seen their brothers promoted to coveted positions—another tactic by which Agrippina bound supporters to herself. For a man who had a brother in

...more

Almost nothing is known of Paul’s life in Rome. But a curious legend holds that while there, he struck up a warm friendship with Seneca.

Agrippina did not think much of philosophy and did not want her son exposed to it. Intellectual musings, she felt, were not what a future emperor needed. She wanted her son taught the more practical arts he would need as princeps, above all rhetoric and declamation. The emphasis that these subjects got is attested by Tacitus, who imagined Nero giving credit to Seneca, later in life, for his eloquence. “You taught me not only how to express myself with prepared remarks, but how to improvise,” the princeps tells his tutor, a remark no doubt invented by Tacitus but based on primary research.

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Tacitus, who knew far more about this relationship than we do, attests that it included bonds of affection. Imagining how Nero might have looked back on these years, the historian has the princeps say to Seneca: “You nurtured my boyhood, then my youth, with your wisdom, advice, and teachings. As long as my life lasts, the gifts you have given me will be eternal.” He goes on to call Seneca praecipuus caritate, foremost in the ranks of those he holds dear. The phrase is ironic, given that the two men had by this time come to hate each other. But Tacitus regarded them as words Nero might

...more

It did not matter much how the young couple felt about each other, for imperial unions were hardly love matches. Their function was to produce an heir and to win Roman hearts by showing them a model of virtuous womanhood. From this second perspective, Octavia made an ideal empress. The Romans liked what they had seen thus far of her sobriety and self-possession.

“Withdraw yourself into calmer, safer, and greater things,” Seneca told his wife’s father. “Do you think these tasks are comparable: to see that grain is transferred to storehouses without being pilfered or neglected in transit, that it’s not damaged by moisture or exposed to heat, that it tallies up by weight and measure; or to approach these holy and lofty matters: to learn what substance God is made of, what experience awaits your soul, what it is that holds the heavy matter of this earth in the middle of the cosmos, raises lighter things above it, and drives the fiery stars to its highest

...more

Claudius drew up his will at this time and had it put under official seal. He could not simply pass on control of the empire as if it were a family heirloom, but bequeathing his personal wealth, an essential resource for anyone running the government, would amount to the same thing. What was in that document, or in Claudius’ mind, concerning his sons? The will was later suppressed, leaving historians both ancient and modern to argue about its contents. Perhaps, as Tacitus, and some modern scholars, believe, it confirmed the selection of Nero; but why then would Nero suppress it? The motive

...more

Poisoning stories bedevil the modern historian even more than scandalous sex tales. No autopsies were held after the death of an emperor. The Romans, like all peoples everywhere, enjoyed skullduggery and conspiracy theories. These were vastly more entertaining than reports of sick old men slowly declining toward death. The truth of whether Claudius was murdered can never be known for certain, and some scholars do not believe he was.

That said, the timing of Claudius’ death is highly suspicious. It fell some three months before Britannicus’ majority, during the last stretch of Nero’s three-year edge. If Claudius had indeed expressed to anyone, or written in his will, any doubts about Nero’s succession, this would have been the perfect time to strike.

Rome had as yet no rituals for the acclamation of a princeps. Only twice before had there been an orderly transfer of power. For lack of a longer tradition, the soldiers adopted the procedure used for Claudius the last time around.