More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 1 - April 2, 2020

On a summer morning the room was delightful to work in, utterly transparent to the breeze and the sounds of birds and squirrels. But because the ceiling had no insulation, by three or so in the afternoon it sometimes got too warm to work. Oh well. The building was telling me to knock off, go for a swim, and so I did. “First we shape our buildings,” Winston Churchill famously said, “and thereafter our buildings shape us.”

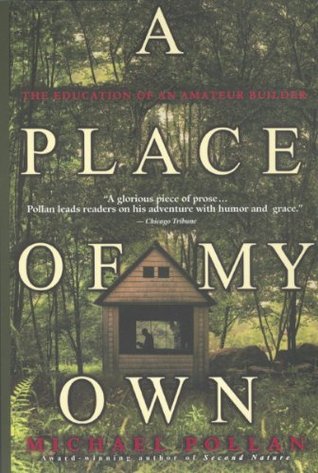

What was surprising, though, and what had no obvious cause or explanation in my life as it had been lived up to then, was a corollary to the dream: I wanted not only a room of my own, but a room of my own making. I wanted to build this place myself.

reflected some doubts I was having about the sort of work I do. Work is how we situate ourselves in the world, and like the work of many people nowadays, mine put me in a relationship to the world that often seemed abstract, glancing, secondhand.

In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf sets more stringent specifications for the space, probably because she is concerned with one particular subset of daydreamer— the female writer—whose requirements are somewhat greater on account of the demands often made on her by others. “A lock on the door,” Woolf writes, “means the power to think for oneself.”

Inside a very human exterior lurks the soul of an architect struggling to get out.

One of the errors in Charlie’s self-conception is that he’s extremely good at hiding his feelings.

Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space is the only book I’ve ever read that takes these sorts of places seriously, analyzing them—or at least our memories and dreams of them—as a way to understand our deepest, most subjective experience of place. He suggests that our sense of space is organized around two distinct poles, or tropisms: one attracting us to the vertical (compelling us to seek the power and rationality of the tower view) and the other to the enclosed center, what he sometimes calls the “hut dream.” It is this second, centripetal attractor that inspires the child to build imaginary huts

...more

It’s almost as though Thoreau’s dream house keeps wanting to dissolve itself back into the landscape; he cannot make his walls thin enough, and has nothing but scorn for the whole hypercivilized distinction between inside and out.

A house in the first person did not seem like something a third party could build. To hire the local Goeltz, to knock the thing off from a picture in a catalog, was to miss the point, or at least, the possibility.

made. To build a house in the first person, a place as much one’s own as a second skin, would require an exploration of self and place—and work itself—that simply could not be delegated to somebody else. The meaning of such a place was in its making.

Painters and writers clearly use different sides of the brain when working, which makes sharing a sound system, if not a space, virtually impossible.

fenestration,

Maybe I’m the kind of person who just needs to think all his second thoughts in advance. As Thoreau pointed out in Walden, there’s freedom in deliberation (literally: “from freedom”); once that’s over, though, things start looking a good deal more fatelike.

His frequent tumultuous efforts to raise a wad of phlegm, the report of which rolled like thunder across the intervening meadow, offered regular reminders that this place wasn’t paradise.

I found it helpful to think of fêng shui as the terrestrial counterpart of astrology. It is concerned with the influence of the earth spirit on human life in much the same way that astrology is concerned with the influence of the heavenly bodies. But while there’s nothing we can do to influence the planets’ paths, there is apparently a great deal we can do to influence the path of chi through a landscape, first through proper site selection and then through site improvement. In this respect fêng shui is a form of gardening. Like picturesque garden theory, it tells you how to improve a

...more

I’m afraid it doesn’t stop there. It’s all I can do to resist the urge to steal a few paragraphs while I’m in the car, pumping gas, or walking down the street (three challenges I’ve met), and even when I’m in social or intimate situations where reading is unquestionably a poor idea. More than once, Judith has caught me as my eyes reached for a line of print right in the middle of a big heart-to-heart.

Like my letter, my drawing was little more than a collage made up of wishes and remembered places, pictures I’d seen and things I’d read. The letter at least had a bit of syntax to keep it from flying apart.

Paging through the book with Charlie, I began to see that the real subject of these pictures was not architectural ideas or styles so much as architectural experiences. Each picture evoked what a particular kind of place or space felt like, they were poetic that way, and it was the sensual nature of each experience, more than any purely visual or aesthetic details, that Charlie meant to call my attention to.

159: Light on Two Sides of Every Room”), defined in a sentence (“People will always gravitate to those rooms which have light on two sides, and leave the rooms which are lit from one side unused and empty”),

“Everybody loves window seats, bay windows, and big windows with low sills and comfortable chairs drawn up to them,” he declares in the pattern “Window Place,” which follows “Alcoves” in A Pattern Language. A room lacking this pattern—even if it has a window and comfortable chair somewhere in it—will “keep you in a state of perpetual unresolved conflict and tension.” That’s because when you enter the room you will feel torn between the desire to sit down and be comfortable and the desire to move toward the light. Only a window place that combines the comfortable spot to sit with the source of

...more

I’d never thought about it before, but having windows on two sides of a room does seem to make the difference between a lifeless and an appealing room. The reason this is so, Alexander hypothesizes, is that a dual light source allows us to see things more intricately, especially the finer details of facial expression and gesture.

“Most of the identity of a dwelling lies in or near its surfaces—in the 3 or 4 feet near the walls.” These should be thick enough to accommodate shelves, cabinets, displays, lamps, built-in furniture—all those nooks and niches that allow people to leave their mark on a place. “Each house will have a memory,” Alexander writes, and the personalities of its inhabitants are “written in the thickness of the walls.” So maybe I hadn’t been that far off, imagining the walls of my hut as an auxiliary brain.

The irreversibility of an action taken in wood is how the carpenter comes by his patience and deliberation, his habit of pausing to mentally walk through all the consequences of any action—to consider fully the implications for, say, the trimming of a doorjamb next month of a cut made in a rafter today.

The status of the carpenter has never fully recovered from the invention of the balloon frame, which replaced posts and beams and mortised joints with slender studs, sills, and joists that just about anybody with a hammer could join with cheap nails.

The balloon frame seems to answer to our longings for freedom and mobility, our penchant for starting over whenever a house or a town or a marriage no longer seems to fit. For a people who moves house as often as we do (typically a dozen times in a lifetime) and likes to remodel each house along the way, a balloon frame is the most logical thing to build, since it is not only quick and inexpensive, but easy to modify as well.

The very lightness and impermanence of a balloon frame may have represented to him a form of hope.

desideratum

People have traditionally turned to ritual to help them frame and acknowledge and ultimately even find joy in just such a paradox of being human—in the fact that so much of what we desire for our happiness and need for our survival comes at a heavy cost. We kill to eat, we cut down trees to build our homes, we exploit other people and the earth. Sacrifice—of nature, of the interests of others, even of our earlier selves—appears to be an inescapable part of our condition, the unavoidable price of all our achievements.

A successful ritual is one that addresses both aspects of our predicament, recalling us to the shamefulness of our deeds at the same time it celebrates what the poet Frederick Turner calls “the beauty we have paid for with our shame.”

Architecture might be done with nature, but the experience of House VI, now on its third roof, suggests that nature will never be done with architecture.

What’s good about 90-degree walls: they don’t catch dust, rain doesn’t sit on them, easy to add to; gravity, not tension, holds them in place. It’s easy to build in counters, shelves, arrange furniture, bathtubs, beds. We are 90 degrees to the earth.

most of them seem designed to look their best uninhabited. Stewart Brand, the author of a recent book on preservation called How Buildings Learn, tells of asking one architect what he learned from revisiting his buildings. “Oh, you never go back,” the architect said, surprised at the question. “It’s too discouraging.”

For the contemporary architect, trained as he is to think of himself as a species of modern artist, surrendering control of his creation is never easy, no matter what he professes to believe about the importance of collaboration.

Much as he might theoretically want to, the modern architect is loath to leave anything to chance or time, much less to the dubious taste of carpenters and clients.

I’d told Charlie in my first letter I wanted a building that was less like a house than a piece of furniture; he’d designed a place that promised to age like one.

The reason ash makes such a satisfactory tool handle is that, in addition to its straight grain and supple strength, the wood is so congenial to our hands, wearing smooth with long use and hardly ever splintering.

One time when I asked Charlie whether or not I should install a piece of trim over one particularly unfortunate gap that a mistake of mine had breached between a fin wall and the desk, he argued against it on the grounds trim here would be too finicky. “It’s okay for a building like this to have a few holidays,” he explained, employing a euphemism for error I’d never heard before;

What began as a safe and private place for a man to keep his accounts and genealogies and most closely held secrets gradually evolved into a place one went to cultivate the self, particularly on the page.

The discovery of silent reading fostered a more solitary and personal relationship with the book. Then there was the new passion for the writing of diaries, memoirs, and, with Montaigne, personal essays—forms that flourished in the private air of the study, a room that is the very embodiment in wood of the first-person singular.