Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

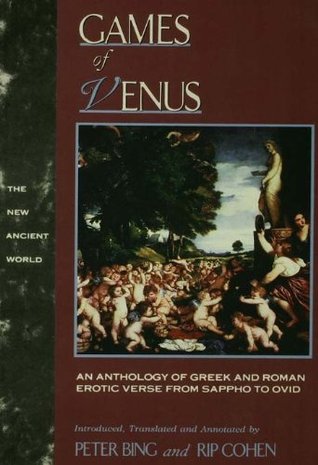

Peter Bing

Read between

July 5 - July 30, 2023

Sexual desire, like most areas of human activity, is culturally determined.

1 There is, for instance, a near total absence of conjugal passion, pervasive differences in status between lover and beloved, the startling prominence of homosexuality,

Much of the ancient Greek poetry we have assembled in this anthology reflects the ideals of the wealthy and aristocratic.

where women of citizen status were segregated from men even in their own households and allowed to go out unaccompanied only on special occasions such as funerals and religious festivals. Still, in a culture with no reliable means of contraception, many obstacles were thrown

Consequently, men were not encouraged to feel sexual desire for women of citizen status. And even for a wife, sexual passion (that strong appetite which the Greeks called eros) on the husband's part was not the norm.

And nowhere in Greek antiquity is love poetry addressed to a spouse.6 On the contrary, we can see just how peculiar

Hetairas were typically hired by just one man (or only a few) over the longer term, and a relationship with one is thought to have included the possibility of real affection and intellectual exchange. On the other hand, slaves were available for quick gratification, and to this end a man could use either his own slaves or

immoderate indulgence in sexual passion could encroach on one's responsibilities as a citizen and

Throughout antiquity homoerotic love was considered normal and appropriate. Nor did it preclude heterosexual activity (including marriage).

Look high and low for the voice of the eromenos in ancient Greek lyric—you will almost never find it.

for a boy to have the intimate companionship of an older male who could act as role-model, inculcating in him those qualities valued by the polis: loyalty to friends and state, valor in war, political responsibility, etc. One scholar has memorably called this “pedagogical pederasty.”

And if an adult of good qualities showed interest in a boy, it was considered flattering—both to the boy and his family. But while an adult was, characteristically, smitten

it was considered disgraceful for a boy to be swayed by a suitor's good looks or wealth, or to yield too soon.

He was expected, rather, to test his suitor's intentions over a period of time and when, finally, he allowed the erastes to achieve his

The evidence of vase-paintings makes clear just how modest the behavior of the eromenos was throughout: in scenes of courtship, we regularly see the erastes fondle a boy's genitals—yet the boy is never shown with an ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

As a rule, the sex act is referred to with metaphor and euphemism.

The twin sites of the pederastic relationship were the palaestra or wrestling ground, where the boy and adult male engaged in physical exercise,

size each other up and initiate contact, and the symposium or male drinking party, where the boy would be integrated into the social group of companions to which his lover belonged, be educated as to its values, and initiated into the ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

komos. Here, if the beloved had not been present at the symposium, the partier would go and try, by means of serenades, pleas, threats, force, etc., to gain admittance to his or her home. This pilgrimage

Roman poets.16 The symposium was the chief poetic locus of the male erotic discourse.

Music was apparently the chief form of entertainment at such a gathering, and it was often performed in turn by the various participants in this intimate circle. The intimacy of the sympotic setting,

Our discussion of the importance of the symposium for the expression of male sexual desire leads us finally to a consideration of its female counterpart, the thiasos, and with it to female homosexuality in the poetic tradition.

Archaic period, in the poetry of Sappho and Alkman.

respectively). In these societies, as it seems, a young girl's training in preparation for marriage was accomplished within a formal group, consisting of many such girls, and known as a thiasos. A sisterhood of this kind was supervised by an older woman who presumably instructed the girls in domestic skills, religious observance, and musical arts. In

the amorous life portrayed in Tibullus, Propertius, and Ovid may be read as an overt act of (political) defiance against Augustus’ legislation.

doesn't have much of a head for business. Other poets also regularly complain about the high price of love, but instead of referring to vulgar cash transactions, they speak of precious gifts they must give the object of their desire. For

The Latin equivalent of hetaira is meretrix, usually rendered in English as “courtesan.”26

there is in fact plenty of evidence that these politicians did not practice what they preached, that hypocrisy, in other words, was common.

These, then, are not names that merely suggest permissive “Greek” sexuality; nor do they refer to “foreigners” and thus to socially acceptable sex objects (that, we recall, was the Archaic and Classical Greek attitude towards foreign women, e.g. Anacreon's “Thracian filly” or his “girl with the flashy slippers,” who comes “from Lesbos,” see above). On the contrary, these names must be taken in a positive sense, as a poet's “graceful compliment.”31

Horace, in this respect, is somewhat exceptional—at least in his Odes. His use of Greek women's names does indeed point to the association of Greeks with the life of luxury in Rome, especially with the symposium. Typically, he does not portray the intense, long-lasting relationships we find in Catullus,

This brings us to the subject of homosexuality. In Rome, homoerotic desire was considered just as normal (and as compatible with heterosexual love) as it was in Greece—though it never developed that status as an essential cultural institution, in which the young were educated and integrated into the political and social fabric, that it had enjoyed in the Hellenic world.

For while it was entirely acceptable for a free-born man to seek gratification with foreign youths, with slaves, or freedmen (as long, that is, as he played the “active” role and not the pathic), a certain stigma—and even legal interdiction—attached to his doing so with a free-born boy.32 This is not to say that such relationships didn't happen.

Catullus describes his love for the noble youth Iuventius (poems 48 and 99),33 he is seriously afraid of legal repercussions.

Finally, a word about female homosexuality. There was in Rome no equivalent to the Greek thiasos where girls were encouraged to explore their sexual feelings for each other prior to getting married. Perhaps if we had any female testimony about the matter our view would be different. But our only references come from men, and these are very few. Those that do exist suggest that men disapproved, that “such behavior was considered ‘masculine’ and unnatural’.”

Every human utterance—at least every one that is intelligible—has a specific context, a time and a place, a speaker and a receiver, and presupposes a common language. It refers to a situation, is part of a person's life, and can only be understood by knowing something about the circumstances, the culture, the relationship existing between speaker and addressee, etc.

The linguistic and social competence of the audience enables it to recognize kinds of action and utterance— and thus also to gauge (roughly) changes, variations, innovations, inversions, and so on. Advised of cultural information they may lack, our readers should—by virtue of their own knowledge of erotic activities and utterances—be able to play this game like their ancient counterparts.

Theognis (with occasional reference to the “First”). We have chosen this corpus because it is the first sizeable group of archaic Greek love poems that has come down to us,

explicitly asks the beloved at least for attention and at most for sexual gratification. We could also call them, ‘boy, be nice’ speeches. Each contains a vocative (‘boy’ or a variation) and an imperative (‘listen,’ ‘stay,’ ‘give,’ etc.).

advice to a boy not to go out ‘reveling,’ which probably implies ‘stay and talk to me instead’ (1351–1352).

Near the other end of the spectrum, but lacking explicit rejection or renunciation, we find poems warning the beloved not to be led astray (i.e. seduced–1238a-b, 1278a-b) or accusing the boy of capriciousness, infidelity or promiscuity (1257–1258, 1259–1262, 1311–1316, 1373–1374), a complaint of ingratitude that seems to refer to the affair as over (1263–1266), a declaration of incompatiblity (1245–1246), and a threat of revenge (1247–1248). Beyond rupture, an ironic greeting to an unfaithful boy apparently serves as a response to an offer to renew the affair (1249–1252).39

Boy, don't wrong me—I still want to please you—listen graciously to this: you won't outstrip me, cheat me with your tricks. Right now you've won and have the upper hand, but I'll wound you while you flee, as they say the virgin daughter of Iasios, though ripe, rejected wedlock with a man and fled; girding herself, she acted pointlessly, abandoning her father's house, blond Atalanta. She went off to the soaring mountain peaks, fleeing the lure of wedlock, golden Aphrodite's gift. But she learned the point she'd so rejected. Here we come upon our first extended mythic exemplum.40 The question,

...more

Another kind of indirectness appears in 1341–1344. Up till now we have looked at requests or wooing speeches spoken directly to the beloved,42 but here we find the speaker talking about the boy: “I love a smooth skinned boy....” The boy has revealed to friends that he and the speaker are involved, and the speaker, though insisting that he's annoyed by this, says he'll put up with it, since the boy is “not unworthy.” Such a confession of love to a third party (apparently spoken to a peer or peers in a sympotic setting, though the audience is not specified) is itself a distinct kind of

...more

Ovid's Amores (3.14), where we need only look at the first verse (Since you're beautiful I don't ask you not to cheat) and the last (You'll be forgiven since the judge is yours) to

For instance, Anacreon PMG 357 “Dionysus, get Kleoboulos to receive my love” would count as a wooing poem. One might be tempted to group these poems according to the carrier, assuming that the primary situation is that existing between the speaker and the deity invoked. In erotic poetry, however, the request to the deity always reveals an intention within the sphere of amorous activity, so we would always treat the prayer as a carrier and the kind of utterance revealed in the request as the governing speech-action. The prayer typically conforms to the following simple pattern: 1) A deity is

...more

The wagon, or cart, is one of a number of common metaphors for love or an amorous relationship. Variants include the yoke and the plow. To be led or driven or pushed to the yoke (or wagon) is to be seduced, involved in a relationship

“Little by little, he'll put his neck in the yoke”

Theognis, whose habitual addressee is Kyrnos,

some fire beneath the ash.

tranquil river undermines a wall.

will slip into me and hurl me into love.