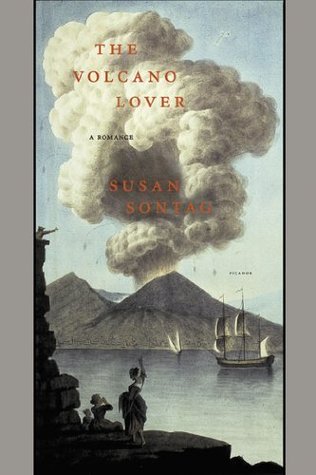

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

collecting was still a virile occupation: not merely recognizing but bestowing value on things, by including them in one’s collection.

Sometimes it felt like exile, sometimes it felt like home.

Sight is a promiscuous sense.

In this instance, nature run amok also makes culture, makes artifacts, by murdering, petrifying history.

He looked into the hole, and like any hole it said, Jump.

They wanted their ration of apocalypse.

People can perform the weightiest actions if these are made to feel weightless.

(its main oddity was that the collector was a woman),

Beauty which is about volume, which is willing to be, cannot choose to be other than, flesh.

But how deprived the thief must feel. It seems most natural to exhibit beauty, to frame it, to stage it—and hear others admire, echo your admiration.

(A truly great beauty always has enough beauty for two.)

The most valuable possession is always identical with itself.

The great collectors are not women, any more than are the great joke-tellers. Collecting, like telling jokes, implies belonging to the world in which already-made objects circulate, are competed for, are transmitted. It presumes confident, full membership in such a world. Women are trained to be marginal or supporting players in that world, as in many others. To compete for approbation—not to compete as such.

Ah, these English. So refined and so coarse. If they did not exist, nobody would ever have invented them.

and had become a kind of Pygmalion in reverse, turning his Fair One into a statue; more accurately, a Pygmalion with a round-trip ticket, for he could change her into a statue and then back into a woman at

To treat the force of history as a force of nature was reassuring as well as distracting.

Being ironical is a way of showing one’s superiority without actually being so ill-bred as to be indignant.

When the right person does the wrong thing, it’s the right thing.

The collecting desire can be enfeebled by happiness—acute enough, erotic enough happiness—and the Cavaliere was happy, as happy as that.

(The Queen had real power, and a woman in power, feared as virile, is often accused of being a slut.

History promoted him. It was a time for concentrated men of preposterous ambition and small stature who needed no more than four hours of sleep a night.

A great man does not have a mean or vulgar appearance, is not maimed or lame, does not squint or have a bulbous nose or an unsightly wig—or if he does, these aren’t part of his essence.

and have decided that high achievers, who are called overachievers,

all people who enjoy making lists are actual or would-be collectors.

It is already a claim, a species of possession, to think about them in this form, the form of a list: which is to value them, to rank them, to say they are worth remembering or desiring.

The Cavaliere has retired to his study and reads, trying not to think about what is going on around him—one of the principal uses of a book.

The Cavaliere was as ill-prepared as any connoisseur of disaster for the real thing.

A lover is never a sceptic.

The influence of women on men has always been disparaged, feared, for its power to make men gentle, loving—weak; which means that women are thought to pose a particular danger for soldiers.

And she was not a woman with a lapful of hero but, in her own way, a hero too.

Though it was still several decades before the Romantics inaugurated the modern cult of thinness, which was eventually to make everyone, men as well as women, feel guilty about not being thin, even then, when it was uncommon for someone wellborn to be thin, she was not to be pardoned for becoming fat.

This may be the kindest form that snobbery can take, but no less obtuse for being kind.

The death of objects can release a grief even more bewildering than the death of a loved person.

This self-deception—this tendency to live beyond his psychological as well as his financial means—is part of the Cavaliere’s abraded talent for happiness, his wish not to be discouraged by anything other than the terminally undesirable.

A revolution is not a good moment for collectors.

To collect is by definition to collect the past—while to make a revolution is to condemn what is now called the past. And the past is very heavy, as well as large.

The value of religion! That was a secret never to be mentioned in public. How guileless they were.

For us, the significant moment is the one that disturbs us most.

Naples became Ireland (or Greece, or Turkey, or Poland). For the sake of the civilized world, said the hero.

They are doing the work of civilization—which always means: the work of empire.

Letting the woman, or women, in the story take the rap is a resourceful way of occluding the full coherence as politics of what was decreed from the hero’s flagship.

Accounts of the Queen invariably reflected the perennial disparagement of women rulers and dominant female consorts—objects of mockery and condescension (for being unbecomingly virile) or of double-standard calumnies (for being frivolous or sexually insatiable).

Churches remind Scarpia of what attracts him in Christianity. Not its doctrines but its historic concern with pain: its palette of inventive martyrdoms, inquisitorial torture, and torments of the damned.

But perhaps we need every model of magnanimity we are offered, including the invented ones.

Mercy, which is not forgiveness, means not doing what nature, and self-interest, tells us we have a right to do. And perhaps we do have the right, as well as the power. How sublime not to, anyway.

Nothing is more odious to me than thinking about the future,

This was the Cavaliere’s first experience of collecting as revenge.