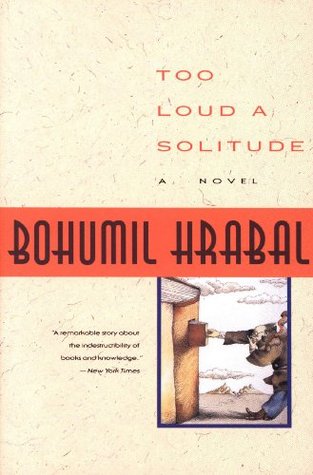

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Because when I read, I don’t really read; I pop a beautiful sentence into my mouth and suck it like a fruit drop, or I sip it like a liqueur until the thought dissolves in me like alcohol, infusing brain and heart and coursing on through the veins to the root of each blood vessel.

When my eye lands on a real book and looks past the printed word, what it sees is disembodied thoughts flying through air, gliding on air, living off air, returning to air, because in the end everything is air, just as the host is and is not the blood of Christ.

And I huddle in the lee of my paper mountain like Adam in the bushes and pick up a book, and my eyes open panic-stricken on a world other than my own, because when I start reading I’m somewhere completely different, I’m in the text, it’s amazing, I have to admit I’ve been dreaming, dreaming in a land of great beauty, I’ve been in the very heart of truth.

I can be by myself because I’m never lonely, I’m simply alone, living in my heavily populated solitude, a harum-scarum of infinity and eternity, and Infinity and Eternity seem to take a liking to the likes of me.

“For we are like olives: only when we are crushed do we yield what is best in us.”

I was always amazed at Hegel and what he taught me, namely, that the only thing on earth worthy of fear is a situation that is petrified, congealed, or dying, and the only thing worthy of joy is a situation where not only the individual but also society as a whole wages a constant battle for self-justification.

life-giving thoughts running through their heads.

when you’re young you love keeping clean, you love your self-image, an image you still have time to improve.

“Two things fill my mind with ever new and increasing wonder—the starry firmament above me and the moral law within me,” but, changing my mind, I leafed through the younger Kant and found an even more beautiful passage: “When the tremulous radiance of a summer night fills with twinkling stars and the moon itself is full, I am slowly drawn into a state of enhanced sensitivity made of friendship and disdain for the world and eternity.”

Immanuel Kant’s Theory of the Heavens

reading the Theory of the Heavens a sentence at a time, savoring each sentence like a cough drop and brimming with a sense of the immensity, grandeur, and infinite beauty streaming at me from all sides, the starry firmament through the hole in the shaft above and the war between the two rat armies in the Prague sewers below.

It never ceased to amaze me, until suddenly one day I felt beautiful and holy for having had the courage to hold on to my sanity after all I’d seen and been through, body and soul, in too loud a solitude, and slowly I came to the realization that my work was hurtling me headlong into an infinite field of omnipotence.

Twenty-one sunflowers lit up the dark cellar and the few mice left shivering for want of paper, and one mouse came up and attacked me, jumping on its hind legs and trying to bite me or knock me over, straining its tiny body, leaping at my leg and gnawing at my wet soles, and each time I brushed it away, gently, it would fling itself at my shoe until finally it ran out of breath and sat in a corner staring at me, staring me right in the eye, and all at once I started trembling, because in that mouse’s eyes I saw something more than the starry firmament above me or the moral law within me.

“From here on in, my boy, you’re on your own. You’re going to have to force yourself to go out and see people and enjoy yourself, playacting until you give up the ghost, because from here on in it’s just one melancholy circle after another and going forward means coming back, that’s right, progressus ad originem equals regressus ad futurum and your brain is nothing but a hydraulic press of compacted thought.”

But I probably won’t go anywhere, because all I need to do is close my eyes and everything I see is clearer than reality, and I prefer just looking at the passersby with their periwinkle faces.

A breeze from the Vltava wafts through the square, I like that, I used to like walking along Letná in the evening, the river scent meeting the park scent, but now the river scent fills the street and I go into BubeníČek’s, sit down, and order a beer absentmindedly, two tons of books perched over my head, a daily sword of Damocles I’ve hung above myself.

“Gentlemen, I am the hangman’s assistant,” whereupon he left, pensive and miserable. Perhaps he was the one who, last year at the Holešovice slaughterhouse, put a knife to my neck, shoved me into a corner, took out a slip of paper, and read me a poem celebrating the beauties of the countryside at Říčany, then apologized, saying he hadn’t found any other way of getting people to listen to his verse.

Novalis