More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“You get work through getting awards, and the award system is based on photographs. Not use. Not context. Just purely visual photographs taken before people start using the building.”

By the early 1990s architecture was adrift—toying with Neo-Modernism, Late Modernism, Second Modernity, Neo-Classicism, Neo-Rationalism, and other signs of being open to renewed investigations of relevance. In an essay titled For an Architecture of Reality, architect Michael Benedikt reminded his colleagues, “We count upon our buildings to form the stable matrix of our lives, to protect us, to stand up to us, to give us addresses, and not to be made of mirrors.”8

Does the building manage to keep the rain out? That’s a core issue seldom mentioned in the magazines but incessantly mentioned by building users, usually through clenched teeth. They can’t believe it when their expensive new building, perhaps by a famous architect, crafted with up-to-the-minute high-tech materials, leaks. The flat roof leaks, the parapets leak, the Modernist right angle between roof and wall leaks, the numerous service penetrations through the roof leak; the wall itself, made of a single layer of snazzy new material and without benefit of roof overhang, leaks. In the 1980s, 80

...more

Architects’ reputations should rot if their buildings can’t handle rain. Frank Lloyd Wright was chosen by a poll of the American Institute of Architects as “the greatest American architect of all time.” They all knew his damp secret: Leaks are a given in any Wright house. Indeed, the architect has been notorious not only for his leaks but for his flippant dismissals of client complaints. He reportedly asserted that, “If the roof doesn’t leak, the architect hasn’t been creative enough.” His stock response to clients who complained of leaking roofs was, “That’s how you can tell it’s a roof.”11

Usually a building is so large and complex an undertaking that the “stakeholders” are too diverse, scattered, and at odds to agree on much of anything.

The percent approach is a conflict of interest for the architect; it encourages buildings that try to be too perfect and too large too soon.

“Architects think of a building as a complete thing, while builders think of it and know it as a sequence—hole, then foundation, framing, roof, etc. The separation of design from making has resulted in a built environment that has no ‘flow’ to it—you simply cannot design an improvisation or an adaptation. It’s dead.”

I recall asking one architect what he learned from his earlier buildings. “Oh, you never go back!” he exclaimed, “It’s too discouraging.” That answer inspired this chapter. In a remarkable study of fifty-eight new business buildings near London, researchers found that in only one case in ten did the architect ever return to the building—and then with no interest in evaluation. The facilities managers interviewed for the study had universally acid views about the architects. One said, “Their primary interest is in aesthetics rather than practicality; it is a ludicrous situation. It’s no good if

...more

Two famed California architects, Bernard Maybeck and Charles Greene (of Greene and Greene), overcame the discontinuity problem by performing constant experiments on their own homes. Those houses became showcases, not of some finished theory, but of lifelong never-finished learning. A walk through their houses was said to be like a walk through the history of their creative development. The instance is noteworthy because it is rare.

In the 1980s, malpractice lawsuits against architects surpassed those against doctors.

architectural magazines. Any one of them could build circulation with a several-year crusade against the scandals in their industry, taking the perspective of the aggrieved users of buildings. People cannot believe that something so obviously important and permanent as buildings can be designed so badly. Unchallenged practices persist for decades—sliding glass doors and floor-to-ceiling glass partitions that people smash their noses on; extensive south- and west-facing windows that become solar ovens; extensive ground-floor windows that people invariably curtain for privacy; women’s rooms

...more

It would be nice to see architecture magazines invent an entertainingly journalistic form of post-occupancy evaluation of famous buildings new and old. Let careers rise and fall on those criteria for a change.

The transition from image architecture to process architecture is a leap from the certainties of controllable things in space to the self-organizing complexities of an endlessly raveling and unraveling skein of relationships over time. Buildings have lives of their own.

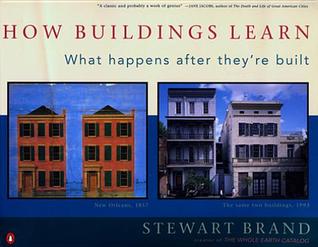

Economists dating back to Aristotle make a distinction between “use value” and “market value.”1 If you maximize use value, your home will steadily become more idiosyncratic and highly adapted over the years. Maximizing market value means becoming episodically more standard, stylish, and inspectable in order to meet the imagined desires of a potential buyer. Seeking to be anybody’s house it becomes nobody’s. Whole neighborhoods tend toward uniformity as everyone avoids being the money-wasting best house on the block or the sore-thumb worst house on the block.

Agencies such as the planning board, design review board, developer’s office, and homeowners’ association decree the size and shape of your lot, where you can build or expand on it, the size and shape of your building, the look of your building, and what you can use it for. The overall rule is always “Fit in.” It is never “Become interesting.” Some buildings become interesting anyway. What you see on the street is the product of the unending conflict between the organizations inside and outside—buildings pretending to fit in or defying fitting in. Each facade asserts, “Don’t worry; nothing

...more

Most building code systems are a manifestation of the whole community learning. What they embody is good sense, acquired the hard way from generations of recurrent problems. Form follows failure. Building codes are an adaptive and local phenomenon. There are 44,000 code-enforcement bodies in the US.

This is an old and interesting problem in organizational learning. How do people learn to do cheap problem-prevention instead of expensive problem-cure?5 There’s no immediate reward for putting in a sprinkler system, only extra nuisance and expense. A larger, slower entity—the community—has to do the learning and instill the lesson, by convention, habit, rite, or law. Convention is preferable to law, being more adaptive, accommodating, and locally appropriate, but a fast-moving society outruns the pace of informal convention and must resort to abstract law.

At their worst, code enforcers block creativity and defy reason, answerable to remote abstractions that have nothing to do with the present case or opportunity. On the widespread estate lands of Chatsworth were a great many solid old stone farm buildings that Deborah Devonshire thought might be nice shelters—“stone tents”—for the teeming hikers and campers in the Peak District. She took the idea to the local authorities: It seemed we might as well have been trying to do in a lot of innocent people. It appeared that anyone using the stone tents would most likely die from having no lavatories,

...more

Jamie Wolf, a professional remodeler in Connecticut, estimates with dismay that only 10-to-15 percent of all remodeling is ever formally given a permit and inspected. The techniques for hiding new work are legion: put stain on the stacks of new lumber and plywood so they are inconspicuous; instantly age the wood siding on new construction by rolling on a slurry of a few handfuls of ready-mix concrete in a few gallons of water; do just a little of the work at a time to avoid complaint or inspection; inside, put down old carpeting on new stairs; make new roof beams look ancient by staining them

...more

In New York City the cost of getting permission for remodeling often exceeds the cost of the work itself. Communities that want their built environment to improve over time would do well not to punish remodeling work. They could keep tax reassessment separate from improvement—do it strictly by calendar or only at the time of resale. They could revamp the permit and inspection process to become one of welcome guidance that helps people reduce costs and hassle. The procedure could even be linked to such services as tool-lending from the town library.

“Cities are always created around whatever the state-of-the-art transportation device is at the time. If the state of the art is sandal leather and donkeys, you get Jerusalem…. The combination of the present is the automobile, the jet plane, and the computer. The result is Edge City.”9

The planning profession keeps oscillating between being destructively radical and destructively conservative. The “urban renewal” disasters of the 1950s and 1960s led to eloquent repudiation by Jane Jacobs’s epochal The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), but their influence lives on in the bloom of homeless people on city streets in the 1980s—there were no “slum” hotels left. So the new suburban developments went in the opposite direction. Garreau defines master planning there as “that attribute of a development in which so many rigid controls are put in place, to defeat every

...more

“Functional Zoning is not an innocent instrument; it has been the most effective means in destroying the infinitely complex social and physical fabric of pre-industrial urban communities, of urban democracy and culture.”15

People find ways around zoning ordinances—quietly setting up home businesses in their garage or basement, quietly moving into industrial lofts—but like barrio dwellers they can succeed only so far before authority discovers and curtails them. Quelling change, zoning quells life.

Vast effort has gone into making the development look nice to a carefully calculated market segment, and that must not be undermined. When you sell your nice house (Americans move every eight years, on average), do you want the prospective buyer to see someone repairing their car or putting out laundry to dry next door? Suppose they’ve got a metal roof instead of tile, or a nonstandard dormer sticking out? Well, if they can’t, you can’t. This degree of institutionalization of real estate value over use value is odious enough as an invasion of privacy, but it also prevents buildings from

...more

In America, according to the Wall Street Journal, “The businesses of financing, building, selling and furnishing real estate account for nearly one-fifth of the nation’s total output.”20

When I began research for this book I was drawn immediately to the preservationists, because they are the only building professionals with a pragmatic interest in the long-term effects of time on buildings. They work creatively with the economics and changing uses of buildings, and they promote expertise in the crafts of longevity. Architectural historians, on the other hand, had almost nothing for me. As a subset of art historians, they are interested only in the history of intention and influence of buildings, never in their use. Like architects, they are pained by what happens later to

...more

“Beauty is in what time does,” says Frank Duffy. Something strange happens when a building ages past a human generation or two. Any building older than 100 years will be considered beautiful, no matter what. Having outlived its period of being out of fashion, plus several passing fashions since that, it is beyond fashion. If it has kept High Road continuity, the whole place is highly adapted, complex and mysterious, a keeper of secrets. Since few buildings live so long, it has earned the stature of rarity and the respect we give longevity.

Durability counts for more and more as our decades grow hastier. “One of the things that people like about older buildings,” says Clem Labine, “is that they were built to last. They have a sense of permanence about them. Up until the 20th century, people thought that they were building for the ages.”

The Economist reported in a special report on tourism and travel that it is the world’s largest industry—$2 trillion in sales annually, employing 6.3 percent of the global workforce. Two-thirds of that number is estimated to be “travel for pleasure.”13 And it keeps growing; world tourism is expected to double by 2010 over what it was in 1993.14

Preservation is now a national pastime in England. The National Trust, founded in 1894, is the largest private landowner in the country, with 1 percent of its total land and 10 percent of its coast.

What alchemy turns a bad old building into a good old building? Vernacular building historian J. B. Jackson insists that a form of death must precede rebirth: “There has to be that interval of neglect, there has to be discontinuity; it is religiously and artistically essential. That is what I mean when I refer to the necessity for ruins: ruins provide the incentive for restoration, and for a return to origins.”26 But busy cities seldom tolerate ruins, and wood ruins can’t survive the elements long. Jackson’s version of reincarnation works best on masonry buildings in the countryside or in old

...more

Adaptive use is the destiny of most buildings, but the subject is not taught in architectural schools. Any kind of remodeling skills are avoided in the schools because they seem so unheroic, and the prospect of remodeling or rehabilitation happening later to one’s new building is even more taboo. Predictably paralyzed buildings are the result. But suppose preservationists taught some of the design courses for architects, developers, and planners. The subject would not be how to make new buildings look like old ones. It would be: how to design new buildings that will endear themselves to

...more

WHO BUILDS IN WOOD builds a shack—adaptable now, gone soon. No other material is so easy to work, and none is so vulnerable to neglect, except maybe adobe. Once the roof and windows of Wright’s Mill were open, even its sturdy timber frame construction could not save it from the effects of constant moisture. To insects and fungus, wet wood is food.

The sequence of effects of deterioration on ordinary buildings has never been formally studied—a curious lapse, considering the massive capital loss involved—but some rules of thumb have emerged. Due to deterioration and obsolescence, a building’s capital value (and the rent it can charge) about halves by twenty years after construction. Most buildings you can expect to require complete refurbishing from eleven to twenty-five years after construction.2 The rule of thumb about abandonment is simple: if repairs will cost half of the value of the building, don’t bother. This is the point at which

...more

The longer that buildings are expected to last, the more you can expect maintenance and other running costs to overwhelm the initial capital costs of construction, and the more inclined owners will be to invest in better construction so they can spend less on maintenance.

Roof effectiveness is determined most by its pitch and shape, next by its detailing, next by its materials, and last by its look, which is irrelevant. Architects who have indulged Post-Modernism’s penchant for pitched roofs—all those triangular gables, even on top of skyscrapers—have been startled to discover that these roofs work better than what they’re used to. That’s because what three generations of architects are used to is flat roofs.

Recent materials such as aluminum or exposed concrete are said to age ugly, but that may be a function of their youth. Just as any building over a hundred years old is declared to be beautiful, any venerable material is given the same courtesy. New materials are unproven, by definition. Like most experiments, they tend to fail. If the experiment is the whole exterior of a highly visible building, they fail big.

by 1980 some 33 percent of lawsuits against architects were for facade failures. “Reliance on a single barrier” is the key defect of new materials. That is what made geodesic domes so leaky. Intelligently designed exterior walls employ what is poetically called “rainscreen” design, which assumes that water will occasionally get through the exterior layer, but it is intercepted and quickly returned to the outside. The multiple layers of shingles, clapboards, and cavity-wall masonry all work that way. Redundancy of function is always more reliable than attempts at perfection, which time treats

...more

“What holds up that house?” one cynical carpenter asked me rhetorically, gesturing at a nearby standard American stick-built home. “Faith, habit, and the dead bodies of termites, same as all the houses around here.” Who builds in wood builds a shack, adaptable now, gone soon.

“the average life of a conventionally built stud house is about 75 years. The life of a timber frame is at least 300 years, and some over 1,000 years old survive.”16

The three things that change a building most are markets, money, and water. If you would ensure a building’s longevity, protect it from markets and water, and feed it money, but not too much and not too little. Too much encourages orgies of radical remodeling that blow a building’s continuity and integrity. Too little, and a building becomes destructive to itself and the people in it. Pressure to cut a building’s running costs inspires such shortcuts as cheaper air filters, replaced less frequently, and a lower rate of air cycling, and mildew left in the ducts. Then suddenly some month

...more

A good maintenance log should document who did the work (and their phone number) and precisely what materials were used and where they came from, right down to the brand, color, and supplier of the paint. Each piece of working equipment should have its manual stored carefully either next to it or in a central archive. Computers are ideal for keeping dynamic records of this sort. Facilities managers are beginning to get sophisticated software that combines the benefits of CAD (computer-aided design), as-built plans, and databases to make a living electronic model of the building in finest

...more

I’d like to see building designers take on problem transparency as a design goal. Use materials that smell bad when they get wet.28 Build in inspection windows and hatches. Expose the parts of service systems that are likeliest to fail. The all-time best models of superb maintenance, both in terms of design and administration, are hospitals and naval ships.

Too often a new building is a teacher of bad maintenance habits. After the initial shakedown period, everything pretty much works, and the owner and inhabitants gratefully stop paying attention to the place. Once attention is deferred, deferring of maintenance comes naturally. It might be better if some of the original work were intentionally ephemeral, with everyone knowing it will require maintenance or replacement within a year. “How might a new building teach good maintenance habits?” is a question worth giving to architecture students.

Eminent folklorist Henry Glassie has described vernacular building tradition in operation: A man wants a house. He talks with a builder. Together they design the house out of their shared experience, their culture of what a house should be. There is no need for formal plans. Students of vernacular architecture search for plans, wish for plans, but should not be surprised that they find none. The existence of plans on paper is an indicator of cultural weakening. The amount of detail in a plan is an exact measure of the degree of cultural disharmony; the more minimal the plan, the more

...more

“a search for pattern in folk material yields regions, where a search for pattern in popular material yields periods.”