More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Almost no buildings adapt well. They’re designed not to adapt; also budgeted and financed not to, constructed not to, administered not to, maintained not to, regulated and taxed not to, even remodeled not to. But all buildings (except monuments) adapt anyway, however poorly, because the usages in and around them are changing constantly.

In wider use, the term “architecture” always means “unchanging deep structure.” It is an illusion. New usages persistently retire or reshape buildings.

The word “building” contains the double reality. It means both “the action of the verb BUILD” and “that which is built”—both verb and noun, both the action and the result. Whereas “architecture” may strive to be permanent, a “building” is always building and rebuilding. The idea is crystalline, the fact fluid. Could the idea be revised to match the fact?

“Form ever follows function.” Written in 1896 by Louis Sullivan, the Chicago highrise designer,

Winston Churchill’s “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.”

First we shape our buildings, then they shape us, then we shape them again—ad infinitum. Function reforms form, perpetually.

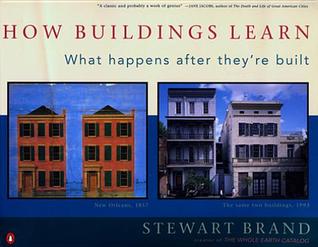

BUILDINGS TELL STORIES, if they’re allowed—if their past is flaunted rather than concealed.

Deterioration is constant, in new buildings as much as old.

Buildings keep being pushed around by three irresistible forces—technology, money, and fashion.

The march of technology is inexorable, and accelerating.

Form follows funding.

As for fashion, it is change for its own sake—

commercial, domestic, and institutional.

Commercial buildings are forever metamorphic.

Domestic buildings—homes—are the steadiest changers, responding directly to the family’s ideas and annoyances, growth and prospects.

Institutional buildings act as if they were designed specifically to prevent change for the organization inside and to convey timeless reliability to everyone outside. When forced to change anyway, as they always are, they do so with expensive reluctance and all possible delay. Institutional buildings are mortified by change.

There is a universal rule—never acknowledged because its action is embarrassing or illegal. All buildings grow.

Things should not be new, but neither should they be rotten with age (except in New Orleans, which fosters a cult of decay).

Some work invites you into itself by not offering a finished, glossy, one-reading-only surface. This is what makes old buildings interesting to me.

Architects and interior designers revile and battle each other.

Gradually the magazine noticed that its affluent readers rebuilt interiors much more often than they built houses.

different parts of buildings change at different rates.

The leading theorist—practically the only theorist—of change rate in buildings is Frank Duffy,

building properly conceived is several layers of longevity of built components.” He distinguishes four layers, which he calls Shell, Services, Scenery, and Set.

Over fifty years, the changes within a building cost three times more than the original building.

“The dynamics of the system will be dominated by the slow components, with the rapid components simply following along.”2 Slow constrains quick; slow controls quick.

The quick processes provide originality and challenge, the slow provide continuity and constraint.

Small lots will support resilience because they allow many people to attend directly to their needs by designing, building, and maintaining their own environment.

And many property owners slow down the rate of change by making large-scale real estate transactions difficult.

Otis Elevator contractors don’t bother to make money on their first installation.

Energy Services such as electricity and gas are driven constantly toward greater efficiency by their sheer expense—30 percent of operating costs, equal over a building’s life to the entire original cost of construction.

An adaptive building has to allow slippage between the differently-paced systems of Site, Structure, Skin, Services, Space plan, and Stuff.

Embedding the systems together may look efficient at first, but over time it is the opposite, and destructive as well.

“Things that are good have a certain kind of structure,” he told me. “You can’t get that structure except dynamically. Period. In nature you’ve got continuous very-small-feedback-loop adaptation going on, which is why things get to be harmonious. That’s why they have the qualities that we value.

“What does it take to build something so that it’s really easy to make comfortable little modifications in a way that once you’ve made them, they feel integral with the nature and structure of what is already there? You want to be able to mess around with it and progressively change it to bring it into an adapted state with yourself, your family, the climate, whatever.

But only sometimes are additions an improvement.

Age plus adaptivity is what makes a building come to be loved. The building learns from its occupants, and they learn from it.

Any change is likely to be an improvement.

elegant because it is quick and dirty.

“We feel our space is really ours. We designed it, we run it. The building is full of small microenvironments, each of which is different and each a creative space. Thus the building has a lot of personality. Also it’s nice to be in a building that has such prestige.”

Temporary is permanent, and permanent is temporary. Grand, final-solution buildings obsolesce and have to be torn down because they were too overspecified to their original purpose to adapt easily to anything else.

Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must come from old buildings.

What do people do to buildings when they can do almost anything they want?

It has all been done by the confident dictators of yesteryear, with no recourse to committees or wondering what other people will think about their additions and subtractions.

Such agglomerations become highly evolved, refinement added to refinement (“The bridge is at a comfortable angle”), the sensible parts kept, the humorous parts kept, the clever idea that didn’t work thrown away, the overambitious conservatory torn down, the loved view carefully maintained, until the aggregate is all finesse and eccentricity. The measure of successful evolution is intricate vivacity.