More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Almost no buildings adapt well. They’re designed not to adapt; also budgeted and financed not to, constructed not to, administered not to, maintained not to, regulated and taxed not to, even remodeled not to. But all buildings (except monuments) adapt anyway, however poorly, because the usages in and around them are changing constantly.

First we shape our buildings, then they shape us, then we shape them again—ad infinitum. Function reforms form, perpetually.

BUILDINGS TELL STORIES, if they’re allowed—if their past is flaunted rather than concealed.

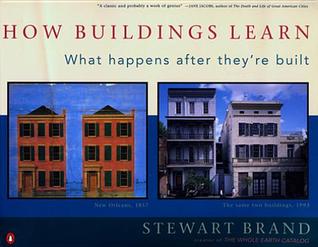

A FIX BECOMES A FEATURE. Add-ons often become a distinctive part of a generic building type. In early Charlestown, South Carolina, a double-story “piazza” (porch) was added on to the British-style townhouses to make them livable in the hot, humid climate. It soon became a famed vernacular—the Charleston “single house.” Similarly, cast-iron balconies added on to New Orleans buildings (often to replace rotting wood balconies) became part of that city’s character.

A question I asked everyone while working on this book was “What makes a building come to be loved?” A thirteen-year-old boy in Maine had the most succinct answer. “Age,” he said. Apparently the older a building gets, the more we have respect and affection for its evident maturity, for the accumulated human investment it shows, for the attractive patina it wears—muted bricks, worn stairs, colorfully stained roof, lush vines.

“A building properly conceived is several layers of longevity of built components.” He distinguishes four layers, which he calls Shell, Services, Scenery, and Set.

“We try to have long-term relationships with clients,” Duffy says. “The unit of analysis for us isn’t the building, it’s the use of the building through time. Time is the essence of the real design problem.”

O’Neill’s A Hierarchical Concept of Ecosystems. O’Neill and his co-authors noted that ecosystems could be better understood by observing the rates of change of different components. Hummingbirds and flowers are quick, redwood trees slow, and whole redwood forests even slower. Most interaction is within the same pace level—hummingbirds and flowers pay attention to each other, oblivious to redwoods, who are oblivious to them. Meanwhile the forest is attentive to climate change but not to the hasty fate of individual trees. The insight is this: “The dynamics of the system will be dominated by the

...more

A design imperative emerges: An adaptive building has to allow slippage between the differently-paced systems of Site, Structure, Skin, Services, Space plan, and Stuff. Otherwise the slow systems block the flow of the quick ones, and the quick ones tear up the slow ones with their constant change. Embedding the systems together may look efficient at first, but over time it is the opposite, and destructive as well.

“What does it take to build something so that it’s really easy to make comfortable little modifications in a way that once you’ve made them, they feel integral with the nature and structure of what is already there? You want to be able to mess around with it and progressively change it to bring it into an adapted state with yourself, your family, the climate, whatever. This kind of adaptation is a continuous process of gradually taking care.”

Age plus adaptivity is what makes a building come to be loved. The building learns from its occupants, and they learn from it.

Low Road buildings are low-visibility, low-rent, no-style, high-turnover. Most of the world’s work is done in Low Road buildings, and even in rich societies the most inventive creativity, especially youthful creativity, will be found in Low Road buildings taking full advantage of the license to try things.

You feel yourself walking in historic footsteps in pursuit of technical solutions that might be elegant precisely because they are quick and dirty. And that describes the building: elegant because it is quick and dirty.

Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must come from old buildings.

Those are the basics of what makes a High Road building acquire its character—high intent, duration of purpose, duration of care, time, and a steady supply of confident dictators. In time such a building comes to express a confidence of its own.

They are not distinguished-looking. What such buildings have instead is an offhand, haphazard-seeming mastery, and layers upon layers of soul. They embody all the meanings of the word “mature”—experienced, complex, subtle, wise, savvy, idiosyncratic, partly hidden, resilient, and set in their ways. Time has taught them, and they teach us.

The problems of “art” as architectural aspiration come down to these: • Art is proudly non-functional and impractical. • Art reveres the new and despises the conventional. • Architectural art sells at a distance.

Art must be inherently radical, but buildings are inherently conservative. Art must experiment to do its job. Most experiments fail. Art costs extra. How much extra are you willing to pay to live in a failed experiment? Art flouts convention. Convention became conventional because it works. Aspiring to art means aspiring to a building that almost certainly cannot work, because the old good solutions are thrown away. The roof has a dramatic new look, and it leaks dramatically.

Art begets fashion; fashion means style; style is made of illusion (granite veneer pretending to be solid; facade columns pretending to hold up something); and illusion is no friend to function. The fashion game is fun for architects to play and diverting for the public to watch, but it’s deadly for building users. When the height of fashion moves on, they’re the ones left behind, stuck in a building that was designed to look good rather than work well, and now it doesn’t even look good. They spend their day trapped in someone else’s taste, which everyone now agrees is bad taste. Here, time

...more

A building’s exterior is a strange thing to concentrate on anyway. All that effort goes into impressing the wrong people—passers-by instead of the people who use the building.

Dome apostate Lloyd Kahn rediscovered verticality: “What’s good about 90-degree walls: they don’t catch dust, rain doesn’t sit on them, easy to add to; gravity, not tension, holds them in place. It’s easy to build in counters, shelves, arrange furniture, bathtubs, beds. We are 90 degrees to the earth.”16 Occupants are always intuitively oriented in rectangular buildings. (Orientation itself is a right-angle concept, the cardinal directions being at 90 degrees.) Since buildings inevitably grow, it is handy to have the five directions (including up) that rectangular buildings offer for

...more

“The fundamental reason is: the difficulty of putting buildings up is so great, and the pressures of getting it right on the night are so enormous, that squeezes out concern for the user and it squeezes out concern for time. I think architects have a tremendous responsibility for change here, because we ought to be the gateway between the construction and the consumer.”

Most architects I know are hustling their tails to survive. They don’t have the time to enrich themselves, to learn. They’re too busy to grow. I think a creative person has to constantly grow, or forget it.”

Architecture magazines could be the monthly avenue of feedback for the profession on what works and doesn’t work. Instead they are the monthly barrier. What architects are kept well abreast of are the things which have advertisers—new materials and new technology. That’s helpful in a world of fast-moving technology, but what is even more needed than simple description is analysis—of reliability, life-cycle behavior, environmental impact, user acceptance, compatibility with other materials, ease of disassembly—the sort of thing that Consumer Reports does for ordinary people.30

We need to honor buildings that are loved rather than merely admired. Admiration is from a distance and brief, while love is up close and cumulative. New buildings should be judged not just for what they are, but for what they are capable of becoming. Old buildings should get credit for how they played their options.

Architecture should offer an incentive to its users to influence it wherever possible, not merely to reinforce its identity, but more especially to enhance and affirm the identity of its users.”

Frank Duffy hectors his profession: “The reason I hate these architectural fleshpots so much is because they represent an aesthetic of timelessness, which is sterile. If you think about what a building actually does as it is used through time—how it matures, how it takes the knocks, how it develops, and you realize that beauty resides in that process—then you have a different kind of architecture. What would an aesthetic based on the inevitability of transience actually look like?”

Form follows failure.

That is the essence of good urban design—respect for what came before.

“People want to get rich quick.” The other side of the coin is, Go broke quick. Real estate is the classic case of soar and collapse, of tycoons going bankrupt and taking shortsighted banks with them. Work done in haste is necessarily shoddy, a house of cards. On a go-fast schedule there is no margin for a single error, and error is inevitable. High risk, high loss. The opposite strategy is much surer, because the errors are piecemeal and correctable. When you proceed deliberately, mistakes don’t cascade, they instruct. Low risk plus time equals high gain. This strategy treats the fundamentals

...more

The present needs a past to grow on, according to Kevin Lynch: “Longevity and evanescence gain savor in each other’s presence…. We prefer a world that can be modified progressively, against a background of valued remains, a world in which one can leave a personal mark alongside the marks of history.”

The building became more interesting when it left its original function behind. The continuing changes in function turn into a colorful story which becomes valued in its own right. The building succeeds by seeming to fail.

This is the formal answer to the question, “Why are old buildings more freeing?” They free you by constraining you. Since you don’t have to address the appalling vacuum of a blank site, you can put all of your effort and ingenuity into the manageable task of rearranging the relatively small part of the building’s mass that people deal with every day—the Services, Space plan, and Stuff. Instead of having to imagine with plans, you can visualize directly in the existing space. “We’ll need another window over there to light this room, which will be much deeper when we take out that wall. And then

...more

PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE (bottom line) not only costs markedly less in aggregate than repairing buildings failures, it reduces human wear and tear. A buildings whose systems are always breaking or threatening to break is depressing to the occupants, and that brings on another dimension of expense.

What you want in materials is a quality of forgivingness.

“Reliance on a single barrier” is the key defect of new materials. That is what made geodesic domes so leaky. Intelligently designed exterior walls employ what is poetically called “rainscreen” design, which assumes that water will occasionally get through the exterior layer, but it is intercepted and quickly returned to the outside. The multiple layers of shingles, clapboards, and cavity-wall masonry all work that way. Redundancy of function is always more reliable than attempts at perfection, which time treats cruelly.

Like all masonry, concrete is subject to deterioration problems such as (alphabetically): blistering, chipping, coving, cracking, crazing, crumbling, delamination, detachment, efflorescence, erosion, exfoliation, flaking, friability, peeling, pitting, rising damp, salt fretting, spalling, subflorescence, sugaring, surface crust, and weathering—most of these caused, as usual, by water.

Alexander elaborated: “Large-lump development is based on the idea of replacement. Piecemeal growth is based on the idea of repair. Since replacement means consumption of resources, while repair means conservation of resources, it is easy to see that piecemeal growth is the sounder of the two from an ecological point of view. But there are even more practical differences. Large-lump development is based on the fallacy that it is possible to build perfect buildings. Piecemeal growth is based on the healthier and more realistic view that mistakes are inevitable…. Unless money is available for

...more

The three things that change a building most are markets, money, and water. If you would ensure a building’s longevity, protect it from markets and water, and feed it money, but not too much and not too little.

Buildings in general should imitate the practice of factories, where the building itself is considered to be the company’s most basic and expensive tool, and it is treated with respect and close attention as a profit center.

Buildings will become automatically self-diagnosing like an office copier or an airplane, and that’s fine. But I’d like to see building designers take on problem transparency as a design goal. Use materials that smell bad when they get wet.28 Build in inspection windows and hatches. Expose the parts of service systems that are likeliest to fail.

“How might a new building teach good maintenance habits?” is a question worth giving to architecture students.

The romance of maintenance is that it has none. Its joys are quiet ones. There is a certain high calling in the steady tending to a ship, to a garden, to a building. One is participating physically in a deep, long life.

Style is time’s fool. Form is time’s student.

Tradition is what you make it. That is, most traditions were once someone’s bright idea which was successful enough to persist long enough for people to forget that it was once someone’s bright idea.

“Some old forms,” he argued, “are so honest, so completely logical and native to the environment that one finds—to one’s delight and surprise—that modern problems can be solved, and are best solved by [the] use of forms based on tradition.”

Successful building forms are broadcast nationally, driven by the national market economy. Builders and developers imitate the most successful of their competition. That is how buildings learn from each other in this century. Whatever buyers flock to will proliferate.

The difference between style and form is the difference between a statement and a language. An architectural statement is limited to a few stylistic words and depends on originality for its impact, whereas a vernacular form unleashes the power of a whole, tested grammar. Builders of would-be popular buildings do better when they learn from folklore than when they ape the elite. As for the elite: what might be accomplished with their abundant intelligence and creativity if architects really studied the process and history of vernacular designs and applied that lore in innovative work? We might

...more

This “inside-out” design approach was thrilling, but it made the profound mistake of taking a snapshot of the high-rate-of-change “organic life” within a building and immobilizing it in a confining carapace—the expensive, low-rate-of-change Structure and Skin of the building. Too eager to please the moment, over-specificity crippled all future moments. It was the image of organic, not the reality. The credo “form follows function” was a beautiful lie. Form froze function.

The trick is to remodel in such a way as to make later remodeling unnecessary or at least easy. Keep furniture mobile. Keep wiring, plumbing, and ducts accessible. Because at some point sooner than you imagine your present arrangement will become suddenly and profoundly intolerable, and you will not be able to rest until you have a Corian island in your kitchen, or a walk-in closet, or a fireplace in the bedroom, or another bathroom, or a skylight over the stairs, or an electronic home theater, or a private study isolated from the noise of the home theater, or whatever it is.