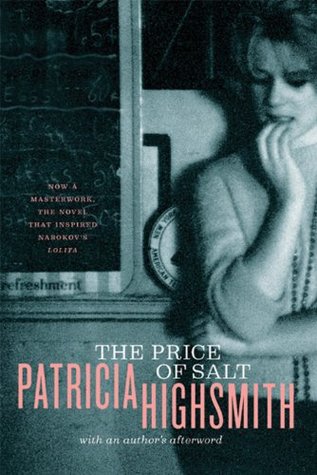

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It was the pointless actions, the meaningless chores that seemed to keep her from doing what she wanted to do, might have done—and here it was the complicated procedures with moneybags, coat checkings, and time clocks that kept people even from serving the store as efficiently as they might—the sense that everyone was incommunicado with everyone else and living on an entirely wrong plane, so that the meaning, the message, the love, or whatever it was that each life contained, never could find its expression.

She never saw her, but it was pleasant to have someone to look for in the store. It made all the difference in the world.

She wished she could kiss the person in the mirror and make her come to life, yet she stood perfectly still, like a painted portrait.

“No, there’s nothing to stop us.” It was easy to say. It was easy to believe all of it, and just as easy not to believe any of it. But if it were all true, if the job were real, the play a success, and she could go to France with at least a single achievement behind her—Suddenly, Therese reached out for Richard’s arm, slid her hand down it to his fingers. Richard was so surprised, he stopped in the middle of a sentence.

from a box she was opening, and the woman just turning her head so she looked directly at Therese. She was tall and fair, her long figure graceful in the loose fur coat that she held open with a hand on her waist. Her eyes were gray, colorless, yet dominant as light or fire, and, caught by them, Therese could not look away.

Her eyebrows were blonde, curving around the bend of her forehead. Her mouth was as wise as her eyes, Therese thought, and her voice was like her coat, rich and supple, and somehow full of secrets.

They roared into the Lincoln Tunnel. A wild, inexplicable excitement mounted in Therese as she stared through the windshield. She wished the tunnel might cave in and kill them both, that their bodies might be dragged out together. She felt Carol glancing at her from time to time.

“They sound horrid.” “They’re not horrid. One’s just supposed to conform. I know what they’d like, they’d like a blank they could fill in. A person already filled in disturbs them terribly. Shall we play some music? Don’t you ever like the radio?”

She did not feel guilty about tonight. It was something else. She envied him. She envied him his faith that there would always be a place, a home, a job, someone else for him. She envied him that attitude. She almost resented his having it.

Therese made fists of her hands in her pockets. She had so hoped Carol would like her work, unqualifiedly. It had hurt her terribly that Carol hadn’t liked in the least a certain few sets she had shown her. Carol knew nothing about it, technically, yet she could demolish a set with a phrase.

Was life, were human relations like this always, Therese wondered. Never solid ground underfoot. Always like gravel, a little yielding, noisy so the whole world could hear, so one always listened, too, for the loud, harsh step of the intruder’s foot.

Carol smiled, and went on nibbling, slowly. “It’s an acquired taste. Acquired tastes are always more pleasant—and hard to get rid of.”

“Do you realize this is the only drink I’ve had since we left New York?” Carol said. “Of course you don’t. Do you know why? I’m happy.”

And she did not have to ask if this was right, no one had to tell her, because this could not have been more right or perfect. She held Carol tighter against her, and felt Carol’s mouth on her own smiling mouth. Therese lay still, looking at her, at Carol’s face only inches away from her, the gray eyes calm as she had never seen them, as if they retained some of the space she had just emerged from. And it seemed strange that it was still Carol’s face, with the freckles, the bending blonde eyebrow that she knew, the mouth now as calm as her eyes, as Therese had seen it many times before.

“They are enough. And you have to live in the world. You, I mean—and I don’t mean anything just now about whom you decide to love.” She looked at Therese, and at last Therese saw a smile rising slowly in her eyes, bringing Carol with it. “I mean responsibilities in the world that other people live in and that might not be yours. Just now it isn’t, and that’s why in New York I was exactly the wrong person for you to know—because I indulge you and keep you from growing up.”

Carol was crying, silently. Therese looked at the downward curve of her lips that was not like Carol at all, but rather like a small girl’s twisted grimace of crying. She stared incredulously at the tear that rolled over Carol’s cheekbone.

“I don’t change my mind,” Carol said.

In the mirror, she saw Carol come up behind her, and there was no answer but the pleasure of Carol’s arms sliding around her, which made it impossible to think, and Therese twisted away more suddenly than she meant to, and stood by the corner of the dressing table looking at Carol, bewildered for a moment by the elusiveness of what they talked about, time and space, and the four feet that separated them now and the two thousand miles. She gave her hair another stroke. “Only about a week?”

The music lived, but the world was dead. And the song would die one day, she thought, but how would the world come back to life? How would its salt come back?

“He feels jilted. His ego’s suffering. Don’t ever think I’m like Richard. I think people’s lives are their own.”