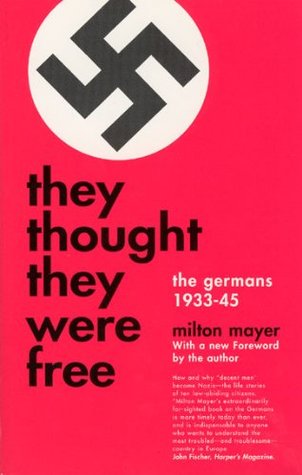

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Hitler had attacked the civilized world, and the civilized world, including by happiest accident the uncivilized Russians, had destroyed him.

there arose a modestly circumscribed sentiment that it might be profitable to find out what it was that had made “the Germans” act as badly as they did.

it was equally difficult to cling to the pleasurable doctrine that the Germans were by nature the enemies of mankind and to cling to the still more pleasurable doctrine that it was possible for one (or two or three) madmen to make and unmake the history of the world.

But to the Europeans—including the Germans—Germany and the Germans are the first order of business every season.

Hitler got them to a pitch and held them there, screaming at them day in and day out for twelve years. They were uneasy through it all. If they believed in Nazism—as all of them did, in substantial part or in all of it—they still got what they could out of it while the getting was good. None of them was astounded when the getting turned bad.

The Germans seem to be less frightening now than they were twenty years ago. If they are, it may be because other people are more frightening now than they were then.

it was ten years ago, and twenty, that the United States Air Force (in its own words) “produced more casualties than any other military action in the history of the world” in its great fire raid on Tokyo, and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, appalled by the absence of public protest in America, thought “there was something wrong with a country where no one questioned” such acts committed in its name

As an American, I was repelled by the rise of National Socialism in Germany. As an American of German descent, I was ashamed. As a Jew, I was stricken. As a newspaperman, I was fascinated.

for the first time realized that Nazism was a mass movement and not the tyranny of a diabolical few over helpless millions.

I never found the average German, because there is no average German.

Now I see a little better how Nazism overcame Germany—not by attack from without or by subversion from within, but with a whoop and a holler.

I came back home a little afraid for my country, afraid of what it might want, and get, and like, under pressure of combined reality and illusion. I felt—and feel—that it was not German Man that I had met, but Man.

Kronenberg went quietly Nazi, and so it was. In the March, 1933, elections, the NSDAP, the National Socialist German Workers Party, had a two-thirds majority, and the Social Democrats went out of office. Only the university—and not the whole university—and the hard-core Social Democrats held out until the end,

This was the work of Dr. Goebbels, whom most people hated and nobody loved;

Sturmführer Schwenke had wanted his oldest son to marry a strong Party woman—any strong Party woman. The boy was not a Party enthusiast, except for anti-Semitism.

Each day he read the headlines of the Daily Kronenberger. He had a copy of Mein Kampf (who hadn’t?), but he had never opened it (who had?).

The “Thousand-Year Reich”?-If it lasts a thousand years, fine; a hundred years, fine; ten years, still fine.

And when I say “little men,” I mean not only the men for whom the mass media and the campaign speeches are everywhere designed but, specifically in sharply stratified societies like Germany, the men who think of themselves in that way.

When “big men,” Hindenburgs, Neuraths, Schachts, and even Hohenzollerns, accepted Nazism, little men had good and sufficient reason to accept it.

I had come to Germany, as a German-descended private person, to bring back to America the life-story of the ordinary German under National Socialism, with the end purpose of establishing better understanding of Germany among my countrymen.

decent, hard-working, ordinarily intelligent and honest men, did not know before 1933 that Nazism was evil. They did not know between 1933 and 1945 that it was evil. And they do not know it now. None of them ever knew, or now knows, Nazism as we knew and know it; and they lived under it, served it, and, indeed, made it.

None of them ever heard anything bad about the Nazi regime except, as they believed, from Germany’s enemies, and Germany’s enemies were theirs. “Everything the Russians and the Americans said about us,” said Cabinetmaker Klingelhöfer, “they now say about each other.”

As there were two Americas, so, in a much more sharply drawn division, there were two Germanys. And so, just as there is when one man dreads the policeman on the beat and another waves “Hello” to him, there are two countries in every country.

The Germans’ innocuous acceptance and practice of social anti-Semitism before Hitlerism had undermined the resistance of their ordinary decency to the stigmatization and persecution to come.

Men who did not know that they were slaves do not know that they have been freed.

This figure represents our own best selves; it is what we ourselves want to be and, through identification, are. To abandon it for anything less than crushing evidence of inexcusable fault is self-incrimination, and of one’s best, unrealized self.

A little man, like ourselves. Such a man is the modern pattern of the demagogical tyrant, “the people’s friend” of Plato’s mob democracy. These Hitlers, Stalins, Mussolinis are commoner upstarts, the half-literate Hitler the commonest of the lot.

The clue to the change (and a radical change it seems to be) may be the emancipation of the German woman and, in particular, of the wife, which Nazism tried to overcome.

this was the closest any of my friends came to knowing of the systematic butchery of National Socialism. I say none of these ten men knew; and, if none of them, very few of the seventy million Germans.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation, with its fantastically rapid development of a central record of an ever increasing number of Americans, law-abiding and lawless, is something new in America. But it is very old in Germany, and it had nothing to do with National Socialism except to make it easier for the Nazi government to locate and trace the whole life-history of any and every German.

These men were, after all, respectable men, like us. The former bank clerk, Kessler, told his Jewish friend, former Bank Director Rosenthal, the day before the synagogue arson in 1938, that “with men like me in the Party,” men of moral and religious feeling, “things will be better, you’ll see.”

Did they know what Communism, “Bolshevism,” was? They did not; not my friends.

the Nazis were able, ultimately, to establish anti-Communism as a religion, immune from inquiry and defensible by definition alone.

Horstmar Rupprecht, the student, had been a Nazi since he was eight years old, in the Jungvolk, the “cub” organization of the Hitler Jugend; his ambition (which he realized) was to be a Hitler Youth leader; in America he would certainly have been a Scoutmaster.

Neither Klingelhöfer nor Wedekind read the Party Program, the historic Twenty-five Points, before they joined, while they were members, or afterward. (Only the teacher, of the ten, ever read it.)

All ten of my friends, including the sophisticated Hildebrandt, were affected by this sense of what the Germans call Bewegung, movement, a swelling of the human sea, something supraparty and suprapolitical, a surge of the sort that does not, at the time, evoke analysis or, afterward, yield to it.

National Socialism was a revulsion by my friends against parliamentary politics, parliamentary debate, parliamentary government—against all the higgling and the haggling of the parties and the splinter parties, their coalitions, their confusions, and their conniving. It was the final fruit of the common man’s repudiation of “the rascals.” Its motif was, “Throw them all out.”

My friends wanted Germany purified. They wanted it purified of the politicians, of all the politicians. They wanted a representative leader in place of unrepresentative representatives.

for Nazism, unlike modern Communism, began with practice. Because the mass movement of Nazism was nonintellectual in the beginning, when it was only practice, it had to be anti-intellectual before it could be theoretical.

Expertness in thinking, exemplified by the professor, by the high-school teacher, and even by the grammar-school teacher in the village, had to deny the Nazi views of history, economics, literature, art, philosophy, politics, biology, and education itself.

In order to be a theory and not just a practice, National Socialism required the destruction of academic independence.

By “they” Herr Schwenke always meant the Jews. He was the most primitive of my ten friends. He was a very limited man. Facts, although he could apprehend them, had no use he could put them to; he could neither retain nor relate them. He could talk, but he could not listen. I let him talk.

I wanted to tell him a story, but I didn’t. It’s a story about a Jew riding in a streetcar, in Germany during the Third Reich, reading Hitler’s paper, the Völkische Beobachter. A non-Jewish acquaintance sits down next to him and says, “Why do you read the Beobachter?” “Look,” says the Jew, “I work in a factory all day. When I get home, my wife nags me, the children are sick, and there’s no money for food. What should I do on my way home, read the Jewish newspaper? ‘Pogrom in Roumania.’ ‘Jews Murdered in Poland.’ ‘New Laws against Jews.’ No, sir, a half-hour a day, on the streetcar, I read the

...more

Conversion and intermarriage simply shifted the emphasis from the economic and the civil to the racial basis of hatred, and, in doing so, invigorated in new and virulent form the anti-Semitism of the “little man,” who, whatever else he was or wasn’t, was of German “blood.”

But the nonexistent wall between the Jews and the “little men” of Germany was as high as ever, and it was a wall with two sides. It was not clearly and simply a matter of exclusion but, rather, of two-way separation, of the independent existence of two communities in one town, a condition which distinguished the small-town situation in Germany from anti-Semitism in, say, the United States.

When people you don’t know, people in whom you have no interest, people whose affairs you have never discussed, move away from your community, you don’t notice that they are going or that they are gone.

nine of my ten friends didn’t know any Jews and didn’t care what happened to them—all this before Nazism.

Not one of my ten friends had changed his attitude toward the Jews since the downfall of National Socialism.

The one passion they seemed to have left was anti-Semitism, the one fire that warmed them still.

the succeeding “international” tribunals at Nuremberg, twelve in all, had to be conducted by the United States without the co-operation of its Allies.