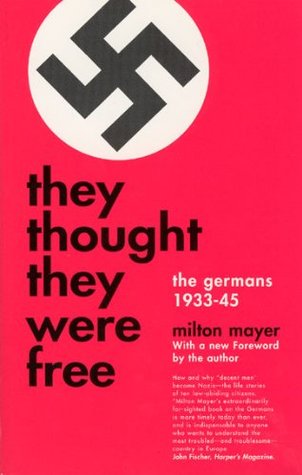

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

If any occupation ever had a chance of succeeding, it should have been the American (sometimes called the Allied) Occupation of western Germany. As occupations went, it was probably the most benign in history,

For the American Occupation to have chosen freedom for the post-Nazi Germans would have been dangerous; even my anti-Nazi friends, so thoroughly German were they, were opposed to freedom of speech, press, and assembly for the “neo-Nazis.” But it was the fear of freedom, with all its dangers, that got the Germans into trouble in the first place. When the Americans decided that they could not “afford” freedom for the Germans, they were deciding that Hitler was right.

the Director of the Development was former Brigadier-General Rheinhardt Gehlen, Nazi intelligence chief in the Soviet Union during the second World War. His new job, said the Paris-Presse, was “to carry on for the United States the work he had begun for Hitler.”

The German press, controlled as it was by the Occupation, expressed itself by the amount of space it gave news, and it gave an extraordinary amount of space to the development of “McCarthyism” in the United States and especially to the incursion of book-burning into the libraries of the Amerika-Häuser.

A new Hitlerism, if it arose in West Germany, would need only one plank in its platform: reunification.

Americans who saw the love of liberty in the East-West refugee traffic and the East German riots needed to remind themselves that these same East Germans lived under totalitarian slavery for twelve years, 1933–45, and loved it. They did not even call it slavery.

But he has no real property, no tangible stake left in the social order. He has nothing to sell but his labor. Marx is talking to him.

And they had not been rehabilitated by American aid. True, “they” had received three billion dollars in aid; true, too, they (without the quotation marks) had paid ten billion dollars in Occupation costs. And the aid, whatever forms it had taken and whichever persons it had reached, was, under the Marshall Plan and its successors, $28 per person in Germany, while it was $63 per person in England and $65 in France.

In this one respect, at least, has Goebbels’ perverse prediction been validated: “Even if we lose, we shall win, for our ideals will have penetrated the hearts of our enemies.”

When we remember what most of them so recently and habitually were, or at least did, it seems hardly worth the trouble, if the Germans must save us, to be saved from Communism.

The proposition that anybody can do anything about anybody else is absolutely indemonstrable.

It is risky to let people alone. But it is riskier still to press my ten Nazi friends—and their seventy million countrymen—to re-embrace militarist anti-Communism as a way of national life.