More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

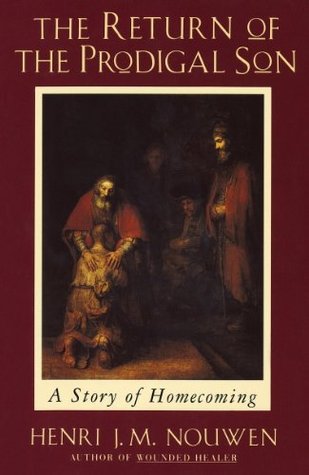

Since my visit to the Hermitage, I had become more aware of the four figures, two women and two men, who stood around the luminous space where the father welcomed his returning son. Their way of looking leaves you wondering how they think or feel about what they are watching. These bystanders, or observers, allow for all sorts of interpretations. As I reflect on my own journey, I become more and more aware of how long I have played the role of observer. For years I had instructed students on the different aspects of the spiritual life, trying to help them see the importance of living it. But

...more

The two women standing behind the father at different distances, the seated man staring into space and looking at no one in particular, and the tall man standing erect and looking critically at the event on the platform in front of him—they all represent different ways of not getting involved. There is indifference, curiosity, daydreaming, and attentive observation; there is staring, gazing, watching, and looking; there is standing in the background, leaning against an arch, sitting with arms crossed, and standing with hands gripping each other. Every one of these inner and outer postures is

...more

a step toward the platform where the father embraces his kneeling son. It is the place of light, the place of truth, the place of love. It is the place where I so much want to be, but am so fearful of being. It is the place where I will receive all I desire, all that I ever hoped for, all that I will ever need, but it is also the place where I have to let go of all I most want to hold on to. It is the place that confronts me with the fact that truly accepting love, forgiveness, and healing is often much harder than giving it. It is the place beyond earning, deserving, and rewarding. It is the

...more

It seems that every time—be it Linda’s welcome, Bill’s handshake, Gregory’s smile, Adam’s silence, or Raymond’s words—I have to make a choice between “explaining” these gestures or simply accepting them as invitations to come higher up and closer by.

In the context of a compassionate embrace, our brokenness may appear beautiful, but our brokenness has no other beauty but the beauty that comes from the compassion that surrounds it.

Faith is the radical trust that home has always been there and always will be there.

Finally there came something very tender, called by some a soft breeze and by others a small voice. When Elijah sensed this, he covered his face because he knew that God was present. In the tenderness of God, voice was touch and touch was voice.

I leave home every time I lose faith in the voice that calls me the Beloved and follow the voices that offer a great variety of ways to win the love I so much desire.

Parents, friends, and teachers, even those who speak to me through the media, are mostly very sincere in their concerns. Their warnings and advice are well intended. In fact, they can be limited human expressions of an unlimited divine love. But when I forget that voice of the first unconditional love, then these innocent suggestions can easily start dominating my life and pull me into the “distant country.” It is not very hard for me to know when this is happening. Anger, resentment, jealousy, desire for revenge, lust, greed, antagonisms, and rivalries are the obvious signs that I have left

...more

As long as I keep running about asking: “Do you love me? Do you really love me?” I give all power to the voices of the world and put myself in bondage because the world is filled with “ifs.”

The world’s love is and always will be conditional. As long as I keep looking for my true self in the world of conditional love, I will remain “hooked” to the world—trying, failing, and trying again. It is a world that fosters addictions because what it offers cannot satisfy the deepest craving of my heart.

As long as we live within the world’s delusions, our addictions condemn us to futile quests in “the distant country,” leaving us to face an endless series of disillusionments while our sense of self remains unfulfilled.

am the prodigal son every time I search for unconditional love where it cannot be found.

It seems to me now that these hands have always been stretched out—even when there were no shoulders upon which to rest them. God has never pulled back his arms, never withheld his blessing, never stopped considering his son the Beloved One. But the Father couldn’t compel his son to stay home. He couldn’t force his love on the Beloved. He had to let him go in freedom, even though he knew the pain it would cause both his son and himself. It was love itself that prevented him from keeping his son home at all cost. It was love itself that allowed him to let his son find his own life, even with

...more

The farther I run away from the place where God dwells, the less I am able to hear the voice that calls me the Beloved, and the less I hear that voice, the more entangled I become in the manipulations and power games of the world.

All at once he saw clearly the path he had chosen and where it would lead him; he understood his own death choice; and he knew that one more step in the direction he was going would take him to self-destruction. In that critical moment, what was it that allowed him to opt for life? It was the rediscovery of his deepest self.

The younger son’s return takes place in the very moment that he reclaims his sonship, even though he has lost all the dignity that belongs to it. In fact, it was the loss of everything that brought him to the bottom line of his identity. He hit the bedrock of his sonship. In retrospect, it seems that the prodigal had to lose everything to come into touch with the ground of his being.

Judas betrayed Jesus. Peter denied him. Both were lost children. Judas, no longer able to hold on to the truth that he remained God’s child, hung himself. In terms of the prodigal son, he sold the sword of his sonship. Peter, in the midst of his despair, claimed it and returned with many tears. Judas chose death. Peter chose life.

It seems that I am perpetually involved in long dialogues with absent partners, anticipating their questions and preparing my responses. I am amazed by the emotional energy that goes into these inner ruminations and murmurings. Yes, I am leaving the foreign country. Yes, I am going home … but why all this preparation of speeches which will never be delivered?

Although claiming my true identity as a child of God, I still live as though the God to whom I am returning demands an explanation. I still think about his love as conditional and about home as a place I am not yet fully sure of.

There is something in us humans that keeps us clinging to our sins and prevents us from letting God erase our past and offer us a completely new beginning.

Receiving forgiveness requires a total willingness to let God be God and do all the healing, restoring, and renewing. As long as I want to do even a part of that myself, I end up with partial solutions, such as becoming a hired servant. As a hired servant, I can still keep my distance, still revolt, reject, strike, run away, or complain about my pay. As the beloved son, I have to claim my full dignity and begin preparing myself to become the father.

Jesus makes it clear that the way to God is the same as the way to a new childhood. “Unless you turn and become like little children you will never enter the Kingdom of Heaven.” Jesus does not ask me to remain a child but to become one. Becoming a child is living toward a second innocence: not the innocence of the newborn infant, but the innocence that is reached through conscious choices.

I am touching here the mystery that Jesus himself became the prodigal son for our sake. He left the house of his heavenly Father, came to a foreign country, gave away all that he had, and returned through his cross to his Father’s home. All of this he did, not as a rebellious son, but as the obedient son, sent out to bring home all the lost children of God. Jesus, who told the story to those who criticized him for associating with sinners, himself lived the long and painful journey that he describes.

I am gradually discovering what it means to say that my sonship and the sonship of Jesus are one, that my return and the return of Jesus are one, that my home and the home of Jesus are one. There is no journey to God outside of the journey that Jesus made. The one who told the story of the prodigal son is the Word of God, “through whom all things came into being.” He “became flesh, lived among us,” and made us part of his fullness.

The parable that Rembrandt painted might well be called “The Parable of the Lost Sons.” Not only did the younger son, who left home to look for freedom and happiness in a distant country, get lost, but the one who stayed home also became a lost man. Exteriorly he did all the things a good son is supposed to do, but, interiorly, he wandered away from his father. He did his duty, worked hard every day, and fulfilled all his obligations but became increasingly unhappy and unfree.

A complainer is hard to live with, and very few people know how to respond to the complaints made by a self-rejecting person. The tragedy is that, often, the complaint, once expressed, leads to that which is most feared: further rejection.

This experience of not being able to enter into joy is the experience of a resentful heart. The elder son couldn’t enter into the house and share in his father’s joy. His inner complaint paralyzed him and let the darkness engulf him.

Jesus confronted the Pharisees and scribes not only with the return of the prodigal son, but also with the resentful elder son. It must have come as a shock to these dutiful religious people. They finally had to face their own complaint and choose how they would respond to God’s love for the sinners. Would they be willing to join them at the table as Jesus did? It was and still is a real challenge: for them, for me, for every human being who is caught in resentment and tempted to settle on a corn-plaintive way of life.

Confronted here with the impossibility of self-redemption, I now understand Jesus’ words to Nicodemus: “Do not be surprised when I say: ‘You must be born from above.’ ” Indeed, something has to happen that I myself cannot cause to happen. I cannot be reborn from below; that is, with my own strength, with my own mind, with my own psychological insights. There is no doubt in my mind about this because I have tried so hard in the past to heal myself from my complaints and failed … and failed … and failed, until I came to the edge of complete emotional collapse and even physical exhaustion. I can

...more

The Father’s love does not force itself on the beloved. Although he wants to heal us of all our inner darkness, we are still free to make our own choice to stay in the darkness or to step into the light of God’s love. God is there. God’s light is there. God’s forgiveness is there. God’s boundless love is there. What is so clear is that God is always there, always ready to give and forgive, absolutely independent of our response. God’s love does not depend on our repentance or our inner or outer changes. Whether I am the younger son or the elder son, God’s only desire is to bring me home.

The fact that the parable is not completed makes it certain that the father’s love is not dependent upon an appropriate completion of the story. The father’s love is only dependent on himself and remains part of his character.

“In the house of my father there are many places to live,” Jesus says. Each child of God has there his or her unique place, all of them places of God. I have to let go of all comparison, all rivalry and competition, and surrender to the Father’s love. This requires a leap of faith because I have little experience of non-comparing love and do not know the healing power of such a love.

Although we are incapable of liberating ourselves from our frozen anger, we can allow ourselves to be found by God and healed by his love through the concrete and daily practice of trust and gratitude. Trust and gratitude are the disciplines for the conversion of the elder son.

The discipline of gratitude is the explicit effort to acknowledge that all I am and have is given to me as a gift of love, a gift to be celebrated with joy.

The choice for gratitude rarely comes without some real effort. But each time I make it, the next choice is a little easier, a little freer, a little less self-conscious. Because every gift I acknowledge reveals another and another until, finally, even the most normal, obvious, and seemingly mundane event or encounter proves to be filled with grace. There is an Estonian proverb that says: “Who does not thank for little will not thank for much.” Acts of gratitude make one grateful because, step by step, they reveal that all is grace.

The leap of faith always means loving without expecting to be loved in return, giving without wanting to receive, inviting without hoping to be invited, holding without asking to be held. And every time I make a little leap, I catch a glimpse of the One who runs out to me and invites me into his joy, the joy in which I can find not only myself, but also my brothers and sisters. Thus the disciplines of trust and gratitude reveal the God who searches for me, burning with desire to take away all my resentments and complaints and to let me sit at his side at the heavenly banquet.

Everything comes together here: Rembrandt’s story, humanity’s story, and God’s story. Time and eternity intersect; approaching death and everlasting life touch each other. Sin and forgiveness embrace; the human and the divine become one.

There he discovers the light that comes from an inner fire that never dies: the fire of love. His art no longer tries to “grasp, conquer, and regulate the visible,” but to “transform the visible in the fire of love that comes from the unique heart of the artist.”

Earlier in his life, Rembrandt had etched and drawn this event with all the dramatic movement it contains. But as he approached death, Rembrandt chose to portray a very still father who recognizes his son, not with the eyes of the body, but with the inner eye of his heart. It seems that the hands that touch the back of the returning son are the instruments of the father’s inner eye. The near-blind father sees far and wide. His seeing is an eternal seeing, a seeing that reaches out to all of humanity. It is a seeing that understands the lostness of women and men of all times and places, that

...more

But his love is too great to do any of that. It cannot force, constrain, push, or pull. It offers the freedom to reject that love or to love in return. It is precisely the immensity of the divine love that is the source of the divine suffering. God, creator of heaven and earth, has chosen to be, first and foremost, a Father.

As Father, the only authority he claims for himself is the authority of compassion. That authority comes from letting the sins of his children pierce his heart. There is no lust, greed, anger, resentment, jealousy, or vengeance in his lost children that has not caused immense grief to his heart. The grief is so deep because the heart is so pure. From the deep inner place where love embraces all human grief, the Father reaches out to his children. The touch of his hands, radiating inner light, seeks only to heal.

Here is the God I want to believe in: a Father who, from the beginning of creation, has stretched out his arms in merciful blessing, never forcing himself on anyone, but always waiting; never letting his arms drop down in despair, but always hoping that his children will return so that he can speak words of love to them and let his tired arms rest on their shoulders. His only desire is to bless.

The Father wants to say, more with his touch than with his voice, good things of his children. He has no desire to punish them. They have already been punished excessively by their own inner or outer waywardness. The Father wants simply to let them know that the love they have searched for in such distorted ways has been, is, and always will be there for them. The Father wants to say, more with his hands than with his mouth: “You are my Beloved, on you my favor rests.” He is the shepherd, “feeding his flock, gathering lambs in his arms, holding them against his breast.”

The Father is not simply a great patriarch. He is mother as well as father. He touches the son with a masculine hand and a feminine hand. He holds, and she caresses. He confirms and she consoles. He is, indeed, God, in whom both manhood and womanhood, fatherhood and motherhood, are fully present.

As I now look again at Rembrandt’s old man bending over his returning son and touching his shoulders with his hands, I begin to see not only a father who “clasps his son in his arms,” but also a mother who caresses her child, surrounds him with the warmth of her body, and holds him against the womb from which he sprang. Thus the “return of the prodigal son” becomes the return to God’s womb, the return to the very origins of being and again echoes Jesus’ exhortation to Nicodemus, to be reborn from above.

The mystery, indeed, is that God in her infinite compassion has linked herself for eternity with the life of her children. She has freely chosen to become dependent on her creatures, whom she has gifted with freedom. This choice causes her grief when they leave; this choice brings her gladness when they return. But her joy will not be complete until all who have received life from her have returned home and gather together around the table prepared for them.

The elder brother compares himself with the younger one and becomes jealous. But the father loves them both so much that it didn’t even occur to him to delay the party in order to prevent the elder son from feeling rejected. I am convinced that many of my emotional problems would melt as snow in the sun if I could let the truth of God’s motherly non-comparing love permeate my heart.

It hadn’t previously occurred to me that the landowner might have wanted the workers of the early hours to rejoice in his generosity to the latecomers. It never crossed my mind that he might have acted on the supposition that those who had worked in the vineyard the whole day would be deeply grateful to have had the opportunity to do work for their boss, and even more grateful to see what a generous man he is. It requires an interior about-face to accept such a non-comparing way of thinking. But that is God’s way of thinking. God looks at his people as children of a family who are happy that

...more

Here lies hidden the great call to conversion: to look not with the eyes of my own low self-esteem, but with the eyes of God’s love. As long as I keep looking at God as a landowner, as a father who wants to get the most out of me for the least cost, I cannot but become jealous, bitter, and resentful toward my fellow workers or my brothers and sisters. But if I am able to look at the world with the eyes of God’s love and discover that God’s vision is not that of a stereotypical landowner or patriarch but rather that of an all-giving and forgiving father who does not measure out his love to his

...more