More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 1 - April 2, 2025

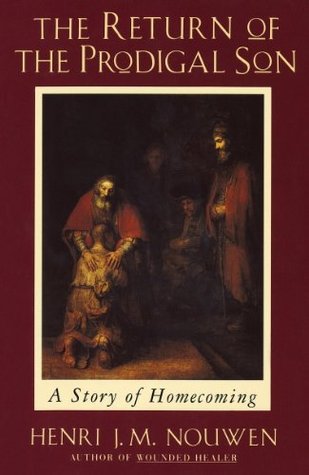

Since my visit to the Hermitage, I had become more aware of the four figures, two women and two men, who stood around the luminous space where the father welcomed his returning son. Their way of looking leaves you wondering how they think or feel about what they are watching. These bystanders, or observers, allow for all sorts of interpretations. As I reflect on my own journey, I become more and more aware of how long I have played the role of observer. For years I had instructed students on the different aspects of the spiritual life, trying to help them see the importance of living it. But

...more

The two women standing behind the father at different distances, the seated man staring into space and looking at no one in particular, and the tall man standing erect and looking critically at the event on the platform in front of him—they all represent different ways of not getting involved. There is indifference, curiosity, daydreaming, and attentive observation; there is staring, gazing, watching, and looking; there is standing in the background, leaning against an arch, sitting with arms crossed, and standing with hands gripping each other. Every one of these inner and outer postures is

...more

It is the place of light, the place of truth, the place of love. It is the place where I so much want to be, but am so fearful of being. It is the place where I will receive all I desire, all that I ever hoped for, all that I will ever need, but it is also the place where I have to let go of all I most want to hold on to. It is the place that confronts me with the fact that truly accepting love, forgiveness, and healing is often much harder than giving it. It is the place beyond earning, deserving, and rewarding. It is the place of surrender and complete trust.

The more I spoke of the Prodigal Son, the more I came to see it as, somehow, my personal painting, the painting that contained not only the heart of the story that God wants to tell me, but also the heart of the story that I want to tell to God and God’s people. All of the Gospel is there. All of my life is there. All of the lives of my friends is there. The painting has become a mysterious window through which I can step into the Kingdom of God. It is like a huge gate that allows me to move to the other side of existence and look from there back into the odd assortment of people and events

...more

More than any other story in the Gospel, the parable of the prodigal son expresses the boundlessness of God’s compassionate love. And when I place myself in that story under the light of that divine love, it becomes painfully clear that leaving home is much closer to my spiritual experience than I might have thought.

the Hermitage painting, made about thirty years later, is one of utter stillness. The father’s touching the son is an everlasting blessing; the son resting against his father’s breast is an eternal peace. Christian Tümpel writes: “The moment of receiving and forgiving in the stillness of its composition lasts without end. The movement of the father and the son speaks of something that passes not, but lasts forever.”

Faith is the radical trust that home has always been there and always will be there.

The somewhat stiff hands of the father rest on the prodigal’s shoulders with the everlasting divine blessing: “You are my Beloved, on you my favor rests.”

At first this sounds simply unbelievable. Why should I leave the place where all I need to hear can be heard? The more I think about this question, the more I realize that the true voice of love is a very soft and gentle voice speaking to me in the most hidden places of my being. It is not a boisterous voice, forcing itself on me and demanding attention. It is the voice of a nearly blind father who has cried much and died many deaths. It is a voice that can only be heard by those who allow themselves to be touched.

But when I forget that voice of the first unconditional love, then these innocent suggestions can easily start dominating my life and pull me into the “distant country.” It is not very hard for me to know when this is happening. Anger, resentment, jealousy, desire for revenge, lust, greed, antagonisms, and rivalries are the obvious signs that I have left home. And that happens quite easily. When I pay careful attention to what goes on in my mind from moment to moment, I come to the disconcerting discovery that there are very few moments during my day when I am really free from these dark

...more

Constantly falling back into an old trap, before I am even fully aware of it, I find myself wondering why someone hurt me, rejected me, or didn’t pay attention to me. Without realizing it, I find myself brooding about someone else’s success, my own loneliness, and the way the world abuses me. Despite my conscious intentions, I often catch myself daydreaming about becoming rich, powerful, and very famous. All of these mental games reveal to me the fragility of my faith that I am the Beloved One on whom God’s favor rests. I am so afraid of being disliked, blamed, put aside, passed over, ignored,

...more

I am the prodigal son every time I search for unconditional love where it cannot be found.

Looking again at Rembrandt’s portrayal of the return of the younger son, I now see how much more is taking place than a mere compassionate gesture toward a wayward child. The great event I see is the end of the great rebellion. The rebellion of Adam and all his descendants is forgiven, and the original blessing by which Adam received everlasting life is restored. It seems to me now that these hands have always been stretched out—even when there were no shoulders upon which to rest them. God has never pulled back his arms, never withheld his blessing, never stopped considering his son the

...more

Rembrandt leaves little doubt about his condition. His head is shaven. No longer the long curly hair with which Rembrandt had painted himself as the proud, defiant prodigal son in the brothel. The head is that of a prisoner whose name has been replaced by a number. When a man’s hair is shaved off, whether in prison or in the army, in a hazing ritual or in a concentration camp, he is robbed of one of the marks of his individuality. The clothes Rembrandt gives him are underclothes, barely covering his emaciated body. The father and the tall man observing the scene wear wide red cloaks, giving

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

What happened to the son in the distant country? Aside from all the material and physical consequences, what were the inner consequences of the son’s leaving home? The sequence of events is quite predictable. The farther I run away from the place where God dwells, the less I am able to hear the voice that calls me the Beloved, and the less I hear that voice, the more entangled I become in the manipulations and power games of the world.

Then, when finally the friendship broke down completely, I had to choose between destroying myself or trusting that the love I was looking for did, in fact, exist … back home! A voice, weak as it seemed, whispered that no human being would ever be able to give me the love I craved, that no friendship, no intimate relationship, no community would ever be able to satisfy the deepest needs of my wayward heart. That soft but persistent voice spoke to me about my vocation, my early commitments, the many gifts I had received in my father’s house. That voice called me “son.” The anguish of

...more

Judas betrayed Jesus. Peter denied him. Both were lost children. Judas, no longer able to hold on to the truth that he remained God’s child, hung himself. In terms of the prodigal son, he sold the sword of his sonship. Peter, in the midst of his despair, claimed it and returned with many tears. Judas chose death. Peter chose life. I realize that this choice is always before me. Constantly I am tempted to wallow in my own lostness and lose touch with my original goodness, my God-given humanity, my basic blessedness, and thus allow the powers of death to take charge. This happens over and over

...more

The reason is clear. Although claiming my true identity as a child of God, I still live as though the God to whom I am returning demands an explanation. I still think about his love as conditional and about home as a place I am not yet fully sure of. While walking home, I keep entertaining doubts about whether I will be truly welcome when I get there. As I look at my spiritual journey, my long and fatiguing trip home, I see how full it is of guilt about the past and worries about the future. I realize my failures and know that I have lost the dignity of my sonship, but I am not yet able to

...more

The prodigal’s return is full of ambiguities. He is traveling in the right direction, but what confusion! He admits that he was unable to make it on his own and confesses that he would get better treatment as a slave in his father’s home than as an outcast in a foreign land, but he is still far from trusting his father’s love. He knows that he is still the son, but tells himself that he has lost the dignity to be called “son,” and he prepares himself to accept the status of a “hired man” so that he will at least survive. There is repentance, but not a repentance in the light of the immense

...more

One of the greatest challenges of the spiritual life is to receive God’s forgiveness. There is something in us humans that keeps us clinging to our sins and prevents us from letting God erase our past and offer us a completely new beginning. Sometimes it even seems as though I want to prove to God that my darkness is too great to overcome. While God wants to restore me to the full dignity of sonship, I keep insisting that I will settle for being a hired servant. But do I truly want to be restored to the full responsibility of the son? Do I truly want to be so totally forgiven that a completely

...more

How can those who have come to this second childhood, this second innocence, be described? Jesus does this very clearly in the Beatitudes. Shortly after hearing the voice calling him the Beloved, and soon after rejecting Satan’s voice daring him to prove to the world that he is worth being loved, he begins his public ministry. One of his first steps is to call disciples to follow him and share in his ministry. Then Jesus goes up onto the mountain, gathers his disciples around him, and says: “How blessed are the poor, the gentle, those who mourn, those who hunger and thirst for uprightness, the

...more

Becoming a child is living the Beatitudes and so finding the narrow gate into the Kingdom. Did Rembrandt know about this? I don’t know whether the parable leads me to see new aspects of his painting, or whether his painting leads me to discover new aspects of the parable. But looking at the head of the boy-come-home, I can see the second childhood portrayed.

When I began to reflect on the parable and Rembrandt’s portrayal of it, I never thought of the exhausted young man with the face of a newborn baby as Jesus. But now, after so many hours of intimate contemplation, I feel blessed by this vision. Isn’t the broken young man kneeling before his father the “lamb of God that takes away the sin of the world”? Isn’t he the innocent one who became sin for us? Isn’t he the one who didn’t “cling to his equality with God,” but “became as human beings are”? Isn’t he the sinless Son of God who cried out on the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken

...more

Once I look at the story of the prodigal son with the eyes of faith, the “return” of the prodigal becomes the return of the Son of God who has drawn all people into himself and brings them home to his heavenly Father. As Paul says: “God wanted all fullness to be found in him and through him to reconcile all things to him, everything in heaven and everything on earth.”

He, who is born not from human stock, or human desire or human will, but from God himself, one day took to himself everything that was under his footstool and he left with his inheritance, his title of Son, and the whole ransom price. He left for a far country … the faraway land … where he became as human beings are and emptied himself. His own people did not accept him and his first bed was a bed of straw! Like a root in arid ground, he grew up before us, he was despised, the lowest of men, before whom one covers his face. Very soon, he came to know exile, hostility, loneliness … After having

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

It is unlikely that Rembrandt himself ever thought of the prodigal son in this way. This understanding was not a customary part of the preaching and writing of his time. Nevertheless, to see in this tired, broken young man the person of Jesus himself brings much comfort and consolation. The young man being embraced by the Father is no longer just one repentant sinner, but the whole of humanity returning to God. The broken body of the prodigal becomes the broken body of humanity, and the baby-like face of the returning child becomes the face of all suffering people longing to reenter the lost

...more

During the year 1649, when these tragic events began to happen, Rembrandt was so consumed by them that he produced no work. At this point another Rembrandt emerges, a man lost in bitterness and desire for revenge, and capable of betrayal. This Rembrandt is hard to face. It is not so difficult to sympathize with a lustful character who indulges in the hedonistic pleasures of the world, then repents, returns home, and becomes a very spiritual person. But appreciating a man with deep resentments, wasting much of his precious time in rather petty court cases and constantly alienating people by his

...more

Rembrandt is as much the elder son of the parable as he is the younger. When, during the last years of his life, he painted both sons in his Return of the Prodigal Son, he had lived a life in which neither the lostness of the younger son nor the lostness of the elder son was alien to him. Both needed healing and forgiveness. Both needed to come home. Both needed the embrace of a forgiving father. But from the story itself, as well as from Rembrandt’s painting, it is clear that the hardest conversion to go through is the conversion of the one who stayed home.

I was familiar only with the detail of the painting in which the father embraces his returning son, it was rather easy to perceive it as inviting, moving, and reassuring. But when I saw the whole painting, I quickly realized the complexity of the reunion. The main observer, watching the father embracing his returning son, appears very withdrawn. He looks at the father, but not with joy. He does not reach out, nor does he smile or express welcome. He simply stands there—at the side of the platform—apparently not eager to come higher up.

Ever since my friend Bart remarked that I may be much more like the elder brother than the younger, I have observed this “man at the right” with more attentiveness and have seen many new and hard things. The way in which the elder son has been painted by Rembrandt shows him to be very much like his father. Both are bearded and wear large red cloaks over their shoulders. These externals suggest that he and his father have much in common, and this commonality is underlined by the light on the elder son which connects his face in a very direct way with the luminous face of his father.

There is light on both faces, but the light from the father’s face flows through his whole body—especially his hands—and engulfs the younger son in a great halo of luminous warmth; whereas the light on the face of the elder son is cold and constricted. His figure remains in the dark, and his clasped hands remain in the shadows.

The parable that Rembrandt painted might well be called “The Parable of the Lost Sons.” Not only did the younger son, who left home to look for freedom and happiness in a distant country, get lost, but the one who stayed home also became a lost man. Exteriorly he did all the things a good son is supposed to do, but, interiorly, he wandered away from his father. He did his duty, worked hard every day, and fulfilled all his obligations but became increasingly unhappy and unfree.

It is strange to say this, but, deep in my heart, I have known the feeling of envy toward the wayward son. It is the emotion that arises when I see my friends having a good time doing all sorts of things that I condemn. I called their behavior reprehensible or even immoral, but at the same time I often wondered why I didn’t have the nerve to do some of it or all of it myself.

In this complaint, obedience and duty have become a burden, and service has become slavery.

All of this became very real for me when a friend who had recently become a Christian criticized me for not being very prayerful. His criticism made me very angry. I said to myself, “How dare he teach me a lesson about prayer! For years he has lived a carefree and undisciplined life, while I since childhood have scrupulously lived the life of faith. Now he is converted and starts telling me how to behave!” This inner resentment reveals to me my own “lostness.” I had stayed home and didn’t wander off, but I had not yet lived a free life in my father’s house. My anger and envy showed me my own

...more

This is not something unique to me. There are many elder sons and elder daughters who are lost while still at home. And it is this lostness—characterized by judgment and condemnation, anger and resentment, bitterness and jealousy—that is so pernicious and so damaging to the human heart. Often we think about lostness in terms of actions that are quite visible, even spectacular. The younger son sinned in a way we can easily identify. His lostness is quite obvious. He misused his money, his time, his friends, his own body. What he did was wrong; not only his family and friends knew it, but he

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The lostness of the elder son, however, is much harder to identify. After all, he did all the right things. He was obedient, dutiful, law-abiding, and hardworking. People respected him, admired him, praised him, and likely considered him a model son. Outwardly, the elder son was faultless. But when confronted by his father’s joy at the return of his younger brother, a dark power erupts in him and boils to the surface. Suddenly, there becomes glaringly visible a resentful, proud, unkind, ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Looking deeply into myself and then around me at the lives of other people, I wonder which does more damage, lust or resentment? There is so much resentment among the “just” and the “righteous.” There is so much judgment, condemnation, and prejudice among the “saints.” There is so mu...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The lostness of the resentful “saint” is so hard to reach precisely because it is so closely wedded to the desire to be good and virtuous. I know, from my own life, how diligently I have tried to be good, acceptable, likable, and a worthy example for others. There was always the conscious effort to avoid the pitfalls of sin and the constant fear of giving in to temptation. But with all of that there came a seriousness, a moralistic intensity—and even a touch of fanaticism—that made it increasingly difficult to feel at home in my...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

It is in this spoken or unspoken complaint that I recognize the elder son in me. Often I catch myself complaining about little rejections, little impolitenesses, little negligences. Time and again I discover within me that murmuring, whining, grumbling, lamenting, and griping that go on and on even against my will. The more I dwell on the matters in question, the worse my state becomes. The more I analyze it, the more reason I see for complaint. And the more deeply I enter it, the more complicated it gets. There is an enormous, dark drawing power to this inner complaint. Condemnation of others

...more

Of one thing I am sure. Complaining is self-perpetuating and counterproductive. Whenever I express my complaints in the hope of evoking pity and receiving the satisfaction I so much desire, the result is always the opposite of what I tried to get. A complainer is hard to live with, and very few people know how to respond to the complaints made by a self-rejecting person. The tragedy is that, often, the complaint, once expressed, leads to that which is most feared: further rejection. From this perspective, the elder son’s inability to share in the joy of his father becomes quite understandable.

...more

The story says: “Calling one of the servants, he asked what it was all about.” There is the fear that I am excluded again, that someone didn’t tell me what was going on, that I was kept out of things. The complaint resurges immediately: “Why was I not informed, what is this all about?” The unsuspecting servant, full of excitement and eager to share the good news, explains: “Your brother has come, and your father has killed the calf we had been fattening because he has got him back safe an...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“He was angry then and refused to go in.” Joy and resentm...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The music and dancing, instead of inviting to joy, become a cause for even greater withdrawal. I have very vivid memories of a similar situation. Once, when I felt quite lonely, I asked a friend to go out with me. Although he replied that he didn’t have time, I found him just a little later at a mutual friend’s house where a party was going on. Seeing me, he said, “Welcome, join us, good to see you.” But my anger was so great at not being told about the party that I couldn’t stay. All of my inner complaints about not being accepted, liked, and loved surged up in me, and I left the room,

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Rembrandt sensed the deepest meaning of this when he painted the elder son at the side of the platform where the younger son is received in the father’s joy. He didn’t depict the celebration, with its musicians and dancers; they were merely the external signs of the father’s joy. The only sign of a party is the relief of a seated flute player carved into the wall against which one of the women (the prodigal’s mother?) leans. In place of the party, Rembrandt painted light, the radiant light that envelops both father and son. The joy that Rembrandt portrays is the still joy that belongs to God’s

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Sometimes, people wonder: Whatever happened to the elder son? Did he let himself be persuaded by his father? Did he finally enter into the house and participate in the celebration? Did he embrace his brother and welcome him home as his father had done? Did he sit down with the father and his brother at the same table and enjoy with them the festive meal? Neither Rembrandt’s painting nor the parable it portrays tells us about the elder son’s final willingness to let himself be found. Is the elder son willi...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.