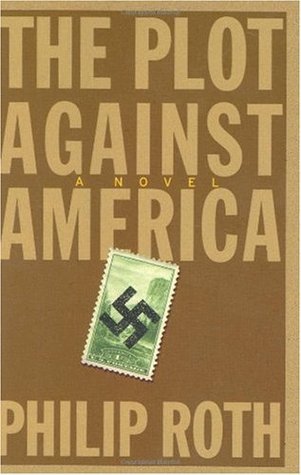

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

When the first shock came in June of 1940—the nomination for the presidency of Charles A. Lindbergh, America’s international aviation hero, by the Republican Convention at Philadelphia—my

It was work that identified and distinguished our neighbors for me far more than religion.

In the course of five visits, during which he was able to familiarize himself at first hand with the magnitude of the German war machine, he was ostentatiously entertained by Air Marshal Göring, he was ceremoniously decorated in the name of the Führer, and he expressed quite openly his high regard for Hitler, calling Germany the world’s “most interesting nation” and its leader “a great man.” And all this interest and admiration after Hitler’s 1935 racial laws had denied Germany’s Jews their civil, social, and property rights, nullified their citizenship, and forbidden intermarriage with

...more

By the time I began school in 1938, Lindbergh’s was a name that provoked the same sort of indignation in our house as did the weekly Sunday radio broadcasts of Father Coughlin, the Detroit-area priest who edited a right-wing weekly called Social Justice and whose anti-Semitic virulence aroused the passions of a sizable audience during the country’s hard times.

It was in November 1938—the darkest, most ominous year for the Jews of Europe in eighteen centuries—that the worst pogrom in modern history, Kristallnacht, was instigated by the Nazis all across Germany: synagogues incinerated, the residences and businesses of Jews destroyed, and, throughout a night presaging the monstrous future, Jews...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When Hitler quickly occupied Denmark, Norway, Holland, and Belgium, and all but defeated France, and the second great European war of the century was well under way, the Air Corps colonel made himself the idol of the isolationists—and the enemy of FDR—by adding to his mission the goal of preventing America from being drawn into the war or offering any aid to the British or the French. There was already strong animosity between him and Roosevelt, but now that he was declaring openly at large public meetings and on network radio and in popular magazines that the president was misleading the

...more

the America First Committee, the broadest-based organization leading the battle against intervention, continued to support him, and he remained the most popular proselytizer of its argument for neutrality. For many America Firsters there was no debating (even with the facts) Lindbergh’s contention that the Jews’ “greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government.” When Lindbergh wrote proudly of “our inheritance of European blood,” when he warned against “dilution by foreign races” and “the infiltration

...more

Booker T. Washington, the first Negro to appear on an American stamp. I remember that after placing the Booker T. Washington in my album and showing my mother how it completed the set of five, I had asked her, “Do you think there’ll ever be a Jew on a stamp?” and she replied, “Probably—someday, yes. I hope so, anyway.” In fact, another twenty-six years had to pass, and it took Einstein to do it.

Did you ever hear of Judah Benjamin?” the rabbi asked Sandy. “No, sir.” But again he quickly righted himself, this time by replying, “May I ask who he was?” “Well, he was a Jew and second only to Jefferson Davis in the government of the Confederacy. He was a Jewish lawyer who served Davis as attorney general, as secretary of war, and as secretary of state. Prior to the secession of the South he had served in the U.S. Senate as one of South Carolina’s two senators. The cause for which the South went to war was neither legal nor moral in my judgment, yet I have always held Judah Benjamin in the

...more

A childhood milestone, when another’s tears are more unbearable than one’s own.

Since what Uncle Monty said to him about Lindbergh was exactly what Rabbi Bengelsdorf had told him—and also what Sandy was secretly saying to me—I began to wonder if my father knew what he was talking about.

When Sandy was my age he used to arm himself against his brand of fear by barreling down the cellar stairs shouting, “Bad guys, I know you’re down there—I’ve got a gun,” while I would descend whispering, “I’m sorry for whatever I did that was wrong.”

Walter Winchell continued to refer to the Bundists as “Bundits,” and Dorothy Thompson, the prominent journalist and wife of novelist Sinclair Lewis, who’d been expelled from the 1939 Bund rally for exercising what she called her “constitutional right to laugh at ridiculous statements in a public hall,” went on denouncing their propaganda in the same spirit she’d demonstrated three years earlier when she’d exited the rally shouting, “Bunk, bunk, bunk! Mein Kampf, word for word!”

“because every day I ask myself the same question: How can this be happening in America? How can people like these be in charge of our country? If I didn’t see it with my own eyes, I’d think I was having a hallucination.”

The larger map was of the forty-eight states and the smaller of just New Jersey, whose long inland river boundary with neighboring Pennsylvania we had been taught in school to identify as the uncanny outline of an Indian chief’s profile, the brow up by Phillipsburg, the nostrils down by Stockton, and the chin narrowing into the neck in the vicinity of Trenton. The state’s densely populated easternmost corner, encompassing Jersey City, Newark, Passaic, and Paterson, and extending northward to the ruler-straight border with the southernmost counties of the state of New York, denoted the upper

...more

nor had I understood till then how the shameless vanity of utter fools can so strongly determine the fate of others.

Their being Jews issued from their being themselves, as did their being American. It was as it was, in the nature of things, as fundamental as having arteries and veins, and they never manifested the slightest desire to change it or deny it, regardless of the consequences.

ultracivilized Jewish Quislings

There were two types of strong men: those like Uncle Monty and Abe Steinheim, remorseless about their making money, and those like my father, ruthlessly obedient to their idea of fair play.

sat on the toilet seat, and that’s when I saw a bathroom for what it is—the upper end of a sewer—and

“The broadcasting cowards,” he told them, “and the billionaire publishing hooligans controlled from the White House by the Lindbergh gang say Winchell was canned for crying ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater. Mr. and Mrs. New York City, the word wasn’t ‘fire.’ It was ‘fascism’ Winchell cried—and it still is. Fascism! Fascism! And I will continue crying ‘fascism’ to every crowd of Americans I can find until Herr Lindbergh’s pro-Hitler party of treason is driven from the Congress on Election Day.

“spontaneous demonstrations” against Germany’s Jews known as Kristallnacht, “the Night of Broken Glass,” whose atrocities had been planned and perpetrated by the Nazis four years earlier and which Father Coughlin in his weekly tabloid, Social Justice, had defended at the time as a reaction by the Germans against “Jewish-inspired Communism.”

The assumption was that these people wouldn’t require much encouragement to be molded into a mindless, destructive mob by the pro-Nazi conspiracy

It’s so heartbreaking, violence, when it’s in a house—like seeing the clothes in a tree after an explosion. You may be prepared to see death but not the clothes in the tree.

regarding the weapon in his hands with all his concentration, as though it were no longer just a weapon but the most serious thing entrusted to him since he’d first been given his infant babies to hold.

Whether outright government-sanctioned persecution was inevitable, nobody could say for sure, but the fear of persecution was such that not even a practical man grounded in his everyday tasks, a person who tried his best to contain the uncertainty and the anxiety and the anger and operate according to the dictates of reason, could hope to preserve his equilibrium any longer.

Fiorello H. La Guardia—the down-to-earth idol of the city’s working people; the flamboyant ex-congressman who’d belligerently represented a congested East Harlem district of poor Italians and Jews for five terms, who as early as 1933 described Hitler as a “perverted maniac” and called for a boycott of German goods; the tenacious spokesman for the unions, the needy, and the unemployed who’d battled almost single-handedly against Hoover’s do-nothing congressional Republicans during the first dark year of the Depression and, to the dismay of his own party, called for taxation to “soak the rich”;

...more

Remorse, predictably, was the form taken by her distress, the merciless whipping that is self-condemnation, as if in times as bizarre as these there were a right way and a wrong way that would have been clear to somebody else, as if in confronting such predicaments the hand of stupidity is ever far from guiding anyone. Yet she reproached herself for errors of judgment that were not only natural when there was no longer a logical explanation for anything but generated by emotions she had no reason to doubt. The worst of it was how convinced she was of her catastrophic blunder, though, had she

...more

Attends 1936 Berlin Olympics, where Hitler is in attendance, and later writes of Hitler to a friend, “He is undoubtedly a great man, and I believe has done much for the German people.” Anne Morrow Lindbergh accompanies her husband to Germany and afterward writes critically of the “strictly puritanical view at home that dictatorships are of necessity wrong, evil, unstable and no good can come of them—combined with our funny-paper view of Hitler as a clown—combined with the very strong (naturally) Jewish propaganda in the Jewish-owned papers.”

Service Cross of the German Eagle—a gold medallion with four small swastikas, conferred on foreigners for service to the Reich—presented to Lindbergh, “by order of the Führer,” by Air Marshal Hermann Göring

SEPTEMBER 1939. In journal entries after Germany invades Poland on September 1, Lindbergh notes the need to “guard ourselves against attack by foreign armies and dilution by foreign races . . . and the infiltration of inferior blood.”

APRIL–AUGUST 1941. Addresses ten thousand at America First Committee rally in Chicago, another ten thousand at New York rally, prompting his bitter enemy Secretary Ickes to call him “the No. 1 United States Nazi fellow traveler.” When Lindbergh writes to President Roosevelt complaining about Ickes’s attacks on him, particularly for accepting the German medal, Ickes writes, “If Mr. Lindbergh feels like cringing when he is correctly referred to as a knight of the German Eagle, why doesn’t he send back the disgraceful decoration and be done with it?” (Earlier, Lindbergh had declined returning the

...more

SEPTEMBER–DECEMBER 1941. Delivers his “Who Are the War Agitators?” radio speech to an America First rally in Des Moines on September 11; audience of eight thousand cheers when he names “the Jewish race” as among those most powerful and effective in pushing the U.S.—“for reasons which are not American”—toward involvement in the war. Adds that “we cannot blame them for looking out for what they believe to be their own interests, but we also must look out for ours. We cannot allow the natural passions and prejudices of other peoples to lead our country to destruction.”

JANUARY–DECEMBER 1942. Travels to Washington to seek reinstatement in Air Corps, but key Roosevelt cabinet members strongly oppose, as does much of the press, and Roosevelt says no. Repeated attempts to find position in aviation industry also fail, despite a lucrative association during the late twenties and early thirties with Transcontinental Air Transport (“the Lindbergh Line”) and as highly paid consultant with Pan American Airways. In spring finally finds work, with government approval, as consultant to Ford’s bomber development program, outside Detroit at Willow Run, and family moves to

...more

1938. In July, on his seventy-fifth birthday, accepts Service Cross of the German Eagle from Hitler’s Nazi government at a birthday dinner in Detroit for fifteen hundred prominent citizens. (Same medal awarded to Lindbergh in October ceremony in Germany, causing Interior Secretary Ickes to tell a December meeting of the Cleveland Zionist Society, “Henry Ford and Charles A. Lindbergh are the only two free citizens of a free country who obsequiously have accepted tokens of contemptuous distinction at a time when the bestower of them counts that day lost when he can commit no new crimes against

...more

1939–1940. With outbreak of World War Two joins his friend Lindbergh in supporting isolationism and America First Committee.

meets regularly with anti-Semitic radio priest Father Coughlin, whose activities Roosevelt and Ickes believe Ford is financing. Lends financial support to the anti-Semitic demagogue Gerald L. K. Smith for his weekly radio broadcast and his living expenses. (Some years later, Smith reprints Ford’s International Jew in a new edition and maintains into the 1960s that Ford “never changed his opinion of Jews.”)