More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

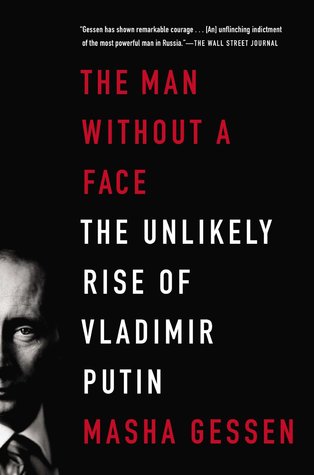

by

Masha Gessen

Read between

May 13 - May 22, 2022

I had spent the 1990s inventing our careers and what we thought were the ways and institutions of a new society. Even as violent crime seemed to become epidemic in Russia, we felt peculiarly secure: we observed and occasionally described the criminal underworld without ever feeling that it might affect our existence.

Russia’s new elite was busy redistributing wealth. This is not to say that all of them behaved like Putin—the scale and the brazen nature of the embezzlement uncovered by Salye is shocking even by early-1990s Russia standards, especially if we take into account how fast he acted—but all of the country’s new rulers treated Russia like their personal property.

Once Putin’s biography was published in February 2000, he ceased being the young democratic reformer of Berezovsky’s invention; he was now the hoodlum turned iron-handed ruler. I do not think his image-makers were even conscious of the shift.

Shchekochikhin was murdered to prevent him from publishing information he had gathered on the theater siege: namely, evidence that some of the women terrorists were convicted felons who, on paper, were still serving sentences in Russian prisons at the time of the siege. In other words, their release had probably been secured by someone who had extralegal powers—and this, again, pointed to possible secret-police involvement in the organization of this act of terror.

The whole edifice of the Russian regime—which, in the eyes of the world, had long since graduated from showing “authoritarian tendencies” to full-fledged authoritarianism bordering on tyranny—rested on this one man, the one Berezovsky thought he had chosen for the country a dozen years earlier.

This meant the current Russian regime was essentially vulnerable: the person or persons to topple it would not have to overcome the force of an ingrained ideology—they would merely have to show that the tyrant had feet of clay. It also meant the tipping point in Russia was as unpredictable as in any tyranny—it could come about in months, years, or decades, triggered perhaps by a small event, most likely the regime’s own mistake that would suddenly make its vulnerability evident.

the Russian blogosphere consisted of discrete circles, each unconnected to any other. It was an anti-utopia of the information age: an infinite number of echo chambers. Nor was this true just of the Internet. The Kremlin was watching its own TV; big business was reading its own newspapers; the intelligentsia was reading its own blogs. None of these groups was aware of the others’ realities, and this made mass protest of any sort seem unlikely.