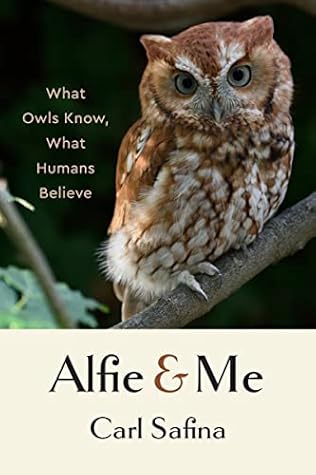

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Carl Safina

Read between

January 17 - February 4, 2024

No two days are the same, regardless of how small and petty and blurry we make them,

English most commonly offers the options of “he” or “she” for humans but generally forces us to refer to other living beings as “it.” Contrastingly, many Native American languages distinguish the living; animate nouns, such as “dog,” take different grammatical forms than do inanimate nouns, like “shoe.” But English conventions strongly favor phrasing such as “The dog that is barking,” not “The dog who is barking.” Language reflects its culture’s values. Our language makes our tongues turn life-forms into mere objects, more easily abused. In English we don’t call a human “it.”

If I may oversimplify: in most ancient and traditional beliefs, the world comprised the most holy and important things; in the European, or “Western,” perspective that developed after Plato, the world was the least holy, least important thing. The Western view has globalized, and the global economy reflects this Western devaluation of the world. And here we are.

The predicament of Life on Earth is that plants make, animals take. All owls are hunters. Unlike Alfie, we have wider choices. And our decisions have greater consequences. Algonquian storyteller Ken Little Hawk tells a story of a boy who asked his grandfather to teach him. The

grandfather took the child to a lake. Giving the boy a stick, he said, “Stir up the water.” The child happily stirred the water and mud and sand and leaves, having fun making a cloudy swirl. Grandfather then instructed, “Now put everything back as before.” The human power to change things exceeds our power to simply put things back as they were. So proceed thoughtfully; reversing course may not be an option.

“Each animal knows way more than you do,” one Athapaskan elder advised. “We always heard that from the old people when they told us never to bother anything unless we really needed it.”

Though spirituality infuses everything, Indigenous beliefs are not “religion” in the Western sense. Indigenous people generally don’t worship gods; rather, they converse with spirits and ancestors as with elders. There are generally no houses specified for worship, no holidays, no scripture, no dogma. No pressure to conform. What it amounts to, writes Native scholar Evan T. Pritchard, is not religion but “a way of life that nurtures deeply religious experiences, which is a different thing.”

original undifferentiated cosmos had separated out into the different things we see. Thousands of years ahead of his time, Anaximander realized that fossil seashells on hilltops indicated that the world had been different, that it changes. He believed that life had originated in moist mud or slime and that land animals—including humans—evolved from fishlike animals. Modern science did not catch up with Anaximander until Lyell, Darwin, and Wallace in the 1800s.

Augustine’s writings reveal an unbalanced fanatic who denigrated his body, human curiosity, and nature. Yet it’s been observed that “Augustine’s impact on Western Christian thought can hardly be overstated.” Augustine was a major influencer on Christianity’s views toward all things natural. The twentieth-century theological writer Francis J. Sheed wrote that Augustine “developed the intellectual framework that allowed Christianity to become the predominant European religion.”

A computer is merely complicated. Living organisms are complex. A cell’s components function with feedback loops subject to intracellular conditions and influence from the outside world. The whole organism is an interaction of genes, history, situation, nutrition, environment, competitive stresses, predation pressures, and luck. Complexity creates unpredictability.

Like most people, Alfie seems to act on things at face value. I used to share her apparent presumption that face-value perceptions are sufficient sensors of reality. I did not know enough to question whether they are. Now I do. Now I understand that the greatest thing one can learn is that learning is a process, that in the great ocean of understanding, we have barely wet a toe. To come to know less than one knew: that is the key that unlocks the universe.

The young one tried to move along the branch several times, but each time slipped and wound up hanging upside down. I expected a fall. But after thrashing a bit, the youngster self-righted. Between these little mishaps, the fledger spent most of the time looking around, attempting with much head bobbing to bring this bewildering new world into some sensible order. Good luck with that; I’ve tried.

At every moment an eyelash of the world is just rolling out of night. And in that eternal dawn, birds are welcoming first light in a chorus that lasts only a few minutes wherever you happen to wake, but has been going on without interruption for tens of millions of years.

The man who has been called “the most influential evangelical anti-environmentalist in the United States,” Calvin Beisner, told an interviewer in 2016 that people should be concerned with the fate of their eternal souls, not about the state of this merely temporary planet—as though it’s somehow necessary to choose. Many of us are enrolled at birth in a lifelong program based on the idea that: I am more important than the world itself. Could any thought be more self-serving?

Owls and other non-human animals know things, as Ben Kilham has said, while we believe things. We are the only animal capable of absorbing centuries of illogic; of perpetuating delusional thinking; and of acting out fervently and violently those things for which there is no evidence, or that evidence, with blinding incandescence, refutes. For millennia the main project of Western thought has been to labor to be who we are not, to loathe our natural selves, to designate and denigrate all “others,” and to disregard our world.

Confucian scholar Tu Weiming has written that Western ideology “is now fully embraced as the unquestioned rationale for development in East Asia.” Tu sees in Western ideology “aggressive anthropocentrism . . . the conspicuous absence of community . . . and the disintegration of human togetherness at all levels from family to the nation.” He says that Western “willingness to tolerate inequality, and the faith in the salvific power of self-interest . . . have greatly poisoned the good well of progress.”

What made Westerners inclined to dominate and colonize was not a more advanced approach to the world—but a more brutal one. The problem is not that modernity requires brutality. It’s that the West chose to create a brutal modernity.

I value individuality; mine, Alfie’s, and others’. But excessive individualism generates isolation. “Someone once asked me,” recalled Native American writer LaDonna Harris, “how I could maintain my individuality as a member of a communal society. I was confused by this question. In fact, I could not even understand it. . . . A strong person strengthens the whole community and a strong community strengthens each person.”

A species is not just a “product” of evolution. When a species declines, it does so because relationships are being unraveled. Extinction is several things. It is a process, an event, a tragedy, a symptom of deeper breakage.

The losses are due mainly to reduction of living space and to climate change.

Mainly, we have taken what they all need to live, snipping the webworks of relation that make them possible. We cannot assess the world’s tens of millions of species individually. But we have a proxy: habitats. At global scale, all major habitat types except deserts are shrinking or degraded. Forests, despite gains in places such as the eastern United States, are at historic lows globally and continue falling and burning. Plows have claimed most grasslands.

Freshwater is at its all-time most degraded and polluted; the oceans and coral reefs are at their most depleted, while also warming, acidifying, plasticizing, and even suffering from a reduced capacity to hold oxygen. The atmosphere today is at its most altered since yesterday. Coral reefs and polar ice systems are fracturing. The World Wildlife Fund’s 2022 Living Planet Report estimated that from 1970 to 2020, wild animal numbers declined 69 percent globally. Their decline is linked to forces auguring our impending decline; sperm counts among Western men have in the last forty years fallen

...more

The trajectory should quite reasonably horrify us. As climate disruption leaves towns burned, dries up rivers, and melts the poles; as plastic gets into our food and pollutants of all kinds affect birth and health and even human procreation; as nearly all wild species continue sagging, it is not because we do not know. It is because we are not taught to care.

I’ve mentioned that when Indigenous people have acquired engines, chain saws, and guns, they have often maintained their cultural values of respectful restraint. For instance, an Athapaskan man explained to Richard Nelson that although he’d trapped in a certain area all his life—and his father before him—“it’s still good ground.” Still lots of beavers, minks, martens, otters, and bears. “I took good care of it . . . don’t take too much out of it

The values from which to grow new answers have been here for centuries. Much of the world’s oldest thinking could scaffold a technological culture in the service of survival, a culture fundamentally different from our current planetary macerator. We could prioritize maintaining the harmonies, as advocated by Confucians. Or attribute to all beings souls of equivalent value, as do many dharmic followers of Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, Sikh, and other beliefs. Or elevate community, place, and all our relations, as do traditional Native American, Australian, African, Hawaiian, Maori, Polynesian, and

...more

Ubuntu is the Bantu term for the traditional African concept “I am because we are.” Its values and practices affirm that a human being is part of a relational world. Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, and the Episcopal Church have all highlighted ubuntu as a guiding concept relevant to modern needs. Ubuntu, writes philosopher and teacher Mark Nepo, implies “the vow to water the common roots by which we all grow.”

Indigenous peoples still struggle to protect their landscapes from the likes of us. They continue defending their lands and waters against our appetites for cheap meat, oil, gas, minerals, metals, and wood. Search online for “Indigenous killed defending”; you’ll see that thousands of Indigenous people have been murdered in recent years—an average of one every two days—for protecting their homelands from illegal loggers, ranchers, and miners.

Nobel-winning physicist Steven Weinberg observed famously and bleakly, “The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.” But what he added matters more: “There is a point that we can give the universe by the way we live . . . that faced with this unloving, impersonal universe we make a little island of warmth and love and science and art for ourselves.”

Cosmic pointlessness, the role of chance in the collisions of matter and energy is, for us little humans over here, existence’s great liberating aspect. It means that our lives are not predetermined. There are only probabilities.

A universe that had a point would create complete conformity. If the cosmos had a goal, all things would be like water in a river. No opportunity to run uphill, to do anything but go with the flow. In a universe with a point, there would be no need for reflection, creativity, yearning, no sadnesses or passion, no need of thought. No freedom. If by magic Life did exist in a universe that had a point, it would be one thing, have one idea, would sing one song. Thank goodness the universe is pointless. It allows us to become.

In New Zealand in 2012, indigenous Maori leaders were able to gain protection for their sacred but threatened Whanganui River by getting the river declared a legal “person” with rights to its own well-being. The Maoris’ negotiator explained, “Rather than us being masters of the natural world, we are part of it. We want to live like that as our starting point. And that is not an anti-development, or anti-economic use of the river but to begin with the view that it is a living being, and then consider its future from that central belief.” Indigenous values hold untapped potential to guide

...more