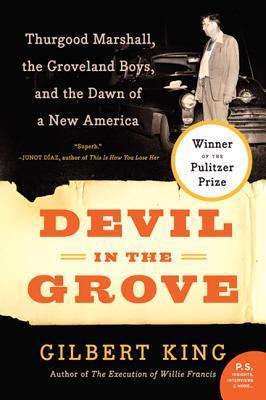

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Gilbert King

Read between

July 2 - July 19, 2021

Marshall, the grandson of a mixed-race slave named Thorney Good Marshall,

southward, closer and closer to benighted towns billeting hostile prosecutors,

virtually angelic faces of the white children, all of them dressed in their Sunday clothes, as they posed, grinning and smiling, in a semicircle around Rubin Stacy’s dangling corpse. In that horrid indifference to human suffering lay the legacy of yet another generation of white children, who, in turn, would without conscience prolong the agony of an entire other race.

“You know,” Marshall said to him, “sometimes I get awfully tired of trying to save the white man’s soul.”

Suicidal or not, Marshall was unquestionably irreplaceable in the mission of the burgeoning civil rights movement.

“Men are needed to sit up all night with a sick friend.” You’d hear it whispered everywhere. They’d all know what it meant. They were lining up armed guards to keep Marshall safe from night-riding Klansmen while he slept.

the spirits of black citizens would be lifted with two words whispered in defiance and hope: “Thurgood’s coming.”

the prosecutor warned them that if they did not convict, “law enforcement would break down and wives of jurymen would die at the hands of Negro assassins.”

Armed and angry, they told the sheriff in no uncertain terms that they were ready if whites came down to the Bottom. “We fought for freedom overseas,” one told him, “and we’ll fight for it here.”

Police had declared war on the black citizens of Columbia, and the highway patrolmen, instead of trying to bring order to the town, had joined in with vigilante mobs.

Marshall knew that nothing good ever happened when police cars drove black men down unpaved roads.

had Looby obeyed police orders and continued driving to Nashville on that November night in 1946, Marshall “would never have been seen again.”

left him exhausted, with no time for exercise—not that he’d ever shown any interest in exercise.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, for his part, was less than enthralled with his wife’s alliance with the NAACP, and the White House attempted to maintain a distance between the president and Eleanor’s activism on behalf of blacks.

The witness stated further that the Communist Party planned to set up a black republic through an armed revolt in the South, extending from Maryland to Texas,

one of dozens of race colonies that had begun to spring up across the nation. There blacks could live a life that was virtually free of racial friction.

Evelyn Cunningham, who later became a noted Harlem columnist and feminist, referred to her friend Thurgood Marshall as one of the “first feminists.”

The most unsettling involved teenage and preteen girls from black communities who were raped and often beaten or killed by advantaged, even prominent white citizens and law enforcement personnel in the South.

W. J. Cash, in his seminal exploration of Southern culture, The Mind of the South,

In a unanimous decision, the nine justices overturned the Florida court’s convictions, thus handing Marshall his first win before the Supreme Court. In delivering the opinion of the Court, Justice Hugo Black wrote an eloquent passage that, his widow later recalled, he “could never read aloud without tears streaming down his face.”

the death penalty for rape was “a sentence that had been more consistently and more blatantly racist in application than any other in American law.”

Sheriff McCall took some highway patrolmen down to Groveland, where he was troubled to see that the Bay Lake men hadn’t gone straight home to their wives and families as he’d suggested.

The company created the Florida Foods Corporation to fulfill the contract, but the war ended shortly thereafter, and the army canceled its order; so the corporation, its research and development completed, shifted its focus to the consumer market, setting up a new entity that would ultimately become Minute Maid Company.

despite a steady flow of European immigrants arriving in America in the early twentieth century, blacks were still the preferred workers. “No white people from any country . . . will . . . submit quietly to such treatment as the common Negro,” read an editorial in the Christmas 1904 edition of Southern Lumberman.

The “Florida bail bond racket” was, according to a former Orlando newspaper editor, the “most lucrative business in the state.”

To make it tougher, on the eve of the election 250 hooded Klansman formed a motorcade that snaked its way through Lake County, “warning blacks not to vote if they valued their lives.”

the stout, illiterate citrus grove caretaker the sheriff himself had on occasion recruited: proficient with a leaded hose in his treatment of black pickers, Evans proved to be useful in helping the law obtain confessions from black suspects in the basement of the Lake County Court House.

He had raised a large family and dramatically improved its economic lot by rising from tenant farmer to landowner, but events over the last few years had left him broken and despondent: a “ravaged ghost” of a man, who was often heard to mumble that he wanted “no more trouble.”

Shepherd confronted them, but to no avail, and when it happened again he called upon Sheriff McCall to help him with the dispute. McCall merely confirmed what Shepherd already knew: “No nigger has any right to file a claim against a white man.”

The lynching of Willie James Howard in January 1944 occurred more than a decade before the fourteen-year-old black youth Emmett Till

From 1882 to 1930, Florida recorded more lynchings of black people (266) than any other state, and from 1900 to 1930, a per capita lynching rate twice that of Mississippi, Georgia, or Louisiana.

By all accounts, Hoover cringed at the start of every civil rights investigation, before “rushing pell-mell” into them at the urging of “vociferous minority groups.”

in the face of the mounting anticommunist fervor he felt the NAACP needed to be viewed by the FBI as a bastion of democracy, not as a target.

and for the first and “only time in the whole investigation,” as McCall would later say, “I violated the law.”

cars had been descending on the area, and men were being deputized in groups to join the manhunt.

Isaac Woodard, who had been maimed by police just hours after receiving his honorable discharge. On February 13, Woodard, in uniform, had boarded a Greyhound bus at Camp Gordon, near Augusta, Georgia, and was heading to South Carolina to pick up his wife

After World War I, dozens of Negro soldiers had been lynched in the South, some of them still wearing their uniforms, and in the summer of 1946 the lynchings of black veterans resumed with a vengeance.

When Williams suggested they might at least ride with the top down, the doctor explained that if the police in rural Florida spotted them, three “negroes in a yellow convertible Cadillac,” they could only expect trouble.

In the South the bargain between justice and the public was implicit: an expeditious trial with swift punishment by death or else a riot and lynching.

She’d once suggested that the New York lawyer might benefit from living some while in the gentlemanly South; without courtesy Williams bellowed, “I would not live in the South!”

getting the education of a lifetime as they worked on briefs not just with Marshall but with academic consultants and top-flight lawyers who were, in Greenberg’s words, willing to use their “considerable talents at something other than getting rich”:

the University of Texas president, Theophilus Painter, had leased the basement of a petroleum building near the state capitol, dumped a few boxes of textbooks inside, and notified the NAACP that there was now a separate law school for blacks

The bailiffs’ commands that the white students not sit in the black section were met by recalcitrance, the students refusing to budge unless a black person requested them to move.

Half the show in Marshall’s courtroom performance was played to those white students outraged by their university’s institutionalized segregation and administrative hypocrisy.

“My son’s been a student at the University of Oklahoma,” the attorney had replied. “He’s read about this case. He’s been berating me about it, including the question whether I really believe in the U.S. Constitution. He convinced me that I was a jackass.”

McLaurin was assigned a special seat in the classroom; it was surrounded by a railing and marked “Reserved for Colored.” The absurdity had not been lost on the white students, who’d immediately torn down the original railing and sign, as well as all the new ones that had replaced them,

Marshall entered the rigorous moot court sessions at Howard “like a boxer going into training,”

It matters not to me whether every single Negro in this country wants segregated schools. It makes no difference whether every white person wants segregated schools. If Sweatt wants to assert his individual, constitutional right, it cannot be conditioned upon the wishes of every other citizen.

Houston had written some last words for his son: Tell Bo I did not run out on him but went down fighting that he might have better and broader opportunities than I had without prejudice or bias operating against him, and in any fight some fall.