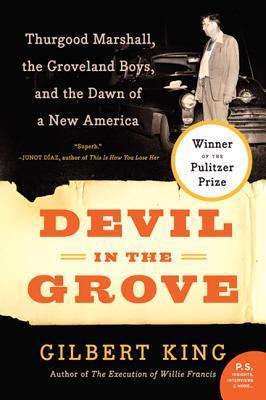

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Gilbert King

Read between

July 2 - July 19, 2021

Norman Bunin, a twenty-six-year-old copy editor who had closely followed the Groveland case as it had unfolded in Florida, had felt that some of the testimony simply did not add up.

The transcripts were astonishing. In hearings that lasted mere minutes, men had been sentenced to life imprisonment.

the only way to stop it was to pick a unit, and court-martial them and make examples of them, and here was this Negro unit. So that’s the one they grabbed.”

“[t]he only chance these Negroes had of acquittal would have been in the courage and decency of some sturdy and forthright white person of sufficient standing to face and live down the odium among his white neighbors that such a vote, if required, would have brought.”

it was not uncommon in central Florida for the KKK to act as an enforcer of community morality, with night riders arriving unannounced and ready to mete out punishment at the home of a white man reported to be beating his wife or at the house of a woman who’d been cheating on her husband or drinking and neglecting her children.

Rights were what white people told him to do; he knew no law beyond that. So he would not even think to question the authority of Deputy Yates. Instead, with his wife he turned and walked away.

Tuck expressed abhorrence at the “sheer, filthy offensiveness of it when Sheriff McCall tells a public inquest that he opened his car window in the rain ‘because the nigger smell got too strong.’ ”

Hunter’s alarm spared Walter Irvin the experience of another two-hour car ride with the man who had shot him not a month before;

Change was coming, but it would be coming sooner with more support from the black community. As Marshall would often remind the NAACP staff and field workers, “the easy part of the job is fighting the white folks.”

Lately he had taken to carrying a pistol. “I’ll take a few of them with me if it comes to that,” Moore told his two daughters and loyal wife.

the judge barred Thurgood Marshall and Jack Greenberg from defending Walter Irvin, on the grounds that they “stirred up trouble in the community.”

The Mount Zion Baptist parishioners reached deep into their pockets that night—their contributions exceeded a thousand dollars—with the highest single donations coming “from some of these white people in the audience.”

in central Florida the line between law enforcement and the KKK had often been indistinct.

Blacks had “come from all directions with their paper bags.” At the midday break they’d gather outside the courthouse and talk together over their bag lunches, for the segregated eateries of downtown Ocala allowed them “no other place to go.”

Not until 1961 would the Supreme Court rule, in Mapp v. Ohio, that evidence obtained in an illegal search was inadmissible in state courts.

Fortunately for the state’s case, the proof of Norma Padgett’s perjury lay buried in an FBI file, which was not in 1949 and would not in 1952 be introduced as evidence in the trial of the Groveland Boys, or boy.

“The only chance these Negroes had of acquittal would have been in the courage and decency of some sturdy and forthright white person of sufficient standing to face and live down the odium among his white neighbors that such a vote, if required, would have brought.”

If the defense saw in him an impressively credentialed criminologist whose testimony would call into question the integrity of the state’s physical evidence, Jesse Hunter saw an elitist big-city windbag, who might not play too well before a “farmer jury.”

Blacks had crowded into the balcony in large part to hear and see Mr. Civil Rights, and to witness possibility; and in “that big Negro” the whites on the main floor might see something of the future.

“You could just see the respect all over [Hunter’s] face for that man. It was such a shame they could never have lunch together, but at the time no restaurant in Florida would have permitted it.”

Racist sentiment had scarcely abated by 1952; at the end of the Briggs proceedings in the same county courthouse Marshall was delivered a stern warning by one of the opposing white lawyers: “If you show your black ass in Clarendon County ever again, you’re a dead man.”

from 1950 to 1960 Florida’s population would grow by almost 80 percent.

Hunter himself, it appeared, had begun to rethink the entire Groveland Boys matter, “due chiefly to the influence of Thurgood Marshall,”

There are enough staid people in the world holding things as they are. We need no more of them.

he cited a Florida newspaper that, in the same day’s edition, covered Irvin’s impending date with death in one article and in another reported that a thirty-year-old white man had been fined a hundred dollars in the rape of a fourteen-year-old black girl.

“it took far more political courage [for Collins] to spare the life of this Negro than it would have taken to let him go to the electric chair.”

Convictions would have carried life sentences for both, if James Yates and his deputy accomplice had ever made it to court, but the case was so long delayed that the statute of limitations expired. Both deputies were reinstated by Willis McCall, with back pay.

Frank Meech, an FBI agent who investigated the Moore killings, was critical of the Department of Justice for having the seven “indictments quashed for the ‘Tranquility of the South.’

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court had ruled that on First Amendment grounds the government could not punish abstract inflammatory speech. The Constitution was the Constitution, and Justice Marshall did not struggle with his vote.

“There is very little truth to the old refrain that one cannot legislate equality,” Marshall posited in a 1966 White House conference on civil rights.