More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

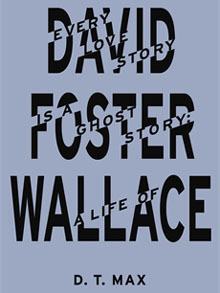

by

D.T. Max

Read between

July 7 - September 23, 2019

Acclaimed in his mid-twenties, burned out and hospitalized for depression and drug and alcohol abuse before he was thirty, he bounced back to write Infinite Jest, the 1,079-page novel about a tennis academy and a halfway house separated by “a tall and more or less denuded hill” that is now widely accepted as the seminal American novel of the 1990s, the best attempt yet at capturing reality in an unreal world.

“In dark times, the definition of good art would seem to be art that locates and applies CPR to those elements of what’s human and magical that still live and glow despite the times’ darkness,”

then go to the dining hall as soon as it opened (they called themselves “the 5:01 brigade”). Wallace would eat his food quickly, with a tea bag dunked into a cup of coffee. At 5:45 he’d head for Frost Library, where he’d study for the next six hours until it closed.

the first story that, as he later put it, “rang his cherries” was Donald Barthelme’s “The Balloon.” Barthelme didn’t tell straightforward stories. He sought to fracture the surface of fiction to show the underpinnings on which its illusions depended. As with other postmodernists, the point was not to make the reader forget the conventions of the charade but to see them more clearly. A truly fulfilled reader was one who always remembered he was just reading a story.

Wallace told an interviewer years later that Barthelme was the first time he heard the “click” in literature. He added that Barthelme’s sort of writing appealed to him far more than the fiction he had enjoyed in high school, writing that contented itself with telling a story.

Lot 49 was an agile and ironic metacommentary, and the effect on Wallace cannot be overstated

Barthelme was hermetic, Pynchon expansive. He tried to take in the enormity of America in a way that Barthelme did not. And he showed you that the tone and sensibility of mainstream culture—Lot 49 drew its energy from pop songs, TV shows, and thrillers—could sit alongside serious issues in fiction. At the very least, the book was funny, and Wallace already knew how to be funny.

he had “a kind of midlife crisis at twenty, which probably doesn’t augur real well for my longevity,”

“One hideous symptom of severe depression is that it is impossible both to do anything and to do nothing; as a devotee of Jumping Joe’s [their logic professor’s] Celebrated Excluded Middle I am sure you can assess that this is an Intolerable Situation.”

(Wallace would one day say that he loved endnotes because they were “almost like having a second voice in your head.”)

He was admitted to Phi Beta Kappa and won three academic awards, one for having the highest grades for his first three years.

After all, late Wittgenstein was Wallace well; early Wittgenstein, the author depressed.

The minute, flirtatious appraisal of women seems borrowed from Nabokov, himself a teacher of Pynchon.

The farrago of forms—stories within stories, transcripts of meetings, duty logs, rock medleys, and madcap set pieces—comes from Pynchon too, as well as from other postmodernists like Barthelme and John Barth.

Wallace’s anxiety, his fear of a world in which nothing is rooted, and his intense attempts to understand what women want and how to form a relationship with them (“How do you know when you can kiss her?”) are apparent.

Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Truth and Method, a book that criticized attempts to turn the study of literature into a science.

Trying to write in a new way was not a goal unique to Wallace; it is the exemplary act of each new literary generation.

Wallace of course had a great fondness for many of the writers of this postmodernist movement, primarily Barthelme (who, as he would say, had “rung his cherries” in college) and Pynchon, whom he had all but engulfed Bombardini-like in The Broom of the System.

As a writer, he was a folder-in and includer, a maximalist, someone who wanted to capture the everything of America.

Wallace was beginning to play around with the props of narrative, rearranging them to see what might catch his attention. He was also going through the various tools in the postmodern tool kit, trying each one out. Part of his goal was to erect a wall between his writing and the pleasure it could give.

It is easy to see why this sort of performance had for so long resonated with Wallace. Metafiction was the sort of technique that had first formed the bridge for him from philosophy to fiction when he was at Amherst. It contained that second level of meaning that made Wallace confident that what he was reading was intellectually richer than just entertainment

Indeed, Barth had been one of the original stars in Wallace’s firmament, along with Barthelme. And in “Lost in the Funhouse,” he shows himself to be just the sort of fiction teacher Arizona lacked—Wallace’s own story featuring diving, “Forever Overhead,” had won great praise in Tucson, even as he saw how thin it was. Barth, then, was the teacher Wallace deserved, “Lost in the Funhouse” the wise, self-aware text his own teachers could never produce to help him on his own way.

To strike down metafiction was also to show what was next, to point the way forward; it was also, in a way, a promise to go beyond what Wallace had been able to achieve in the stories he’d written at Arizona in their farrago of postmodern styles.

Wallace’s suggestion is clear: advertising and metafiction share the same goal, to lull by pleasing, to fatten without nourishing.

There is a sense—again brought to full boil in Infinite Jest—that our obsession with being entertained has deadened our affect, that we are not, as a character warns in that book, choosing carefully enough what to love.

The older McInerney was surprised to find Wallace so obsessed with postmodernism; for him and his peers it had largely ceased to matter.

become a friend and, like nearly all Wallace’s friends, wondered why Wallace

held “Westward” in such special regard, that the novella was in my view far and away the best piece of sustained fiction I’ve ever written. It is exactly what I wanted it to be [and is] also truly about everything I either had to write about or die in ’87…. My hope is that it succeeds on about 12 different levels, depending on whether you’re more interested in advertising or 80’s fiction or 60’s metafiction or the revelations of John—disciple not Barth or etc.

At the core the problem for Wallace was what to write next. He had said what he had to say in “Westward.” It was what he had been born to write, and having done so, as he would later explain to an interviewer, he had “killed this huge part of myself doing it.”

Since finishing the novella, he hadn’t written a word; the story, he realized, as he would tell a later interviewer, was also “a kind of suicide note”—if he wasn’t precisely a metafictionist, he was certainly someone for whom pulling off the façade of realism was congenial.

The American generation born after, say, 1955 is the first for whom television is something to be lived with, not just looked at. Our parents regard the set rather as the Flapper did the automobile: a curiosity turned treat turned seduction. For us, their children, TV’s as much a part of reality as Toyotas and gridlock. We quite literally cannot “imagine” life without it.

Wallace believed the “three dreary camps” of current fiction writers corresponded to three different responses to this insidious force. One camp consisted of the young hip brat pack writers like McInerney and Ellis, whom he defined as practicing “Neiman-Marcus Nihilism, declaimed via six-figure Uppies and their salon-tanned, morally vacant offspring.” A second camp were the minimalists. He characterized their style as “Catatonic Realism, a.k.a. Ultraminimalism, a.k.a. Bad Carver.” And the third was just about every other writer he’d ever read, especially those favored by his teachers at

...more

Wallace allowed that some critics might see minimalism or postmodernism as attempts to escape the prison of modern television-shaped reality, but he argued forcefully that they were each too limited to solve the problem: Both these forms strike me as simple engines of self-reference (Metafiction overtly so, Minimalism a bit sneakier); they are primitive, crude, and seem already to have reached the Clang-Bird-esque horizon of their own possibility. For Wallace, the great flaw of most fiction was that it was content to display the symptoms of the current malaise rather than to solve it. Wallace

...more

Wallace was also a habitual top student; when he took a class he wanted to ace it. He invoked thinkers from Aristotle to Wittgenstein in an attempt to understand just what or whom he would be surrendering to. Rich C. sought to simplify the challenge: “All this step says is are you willing to make a decision.” For the first time in his life, Wallace found his outsized intelligence a liability. To do well in recovery required modesty rather than brilliance. It was not easy for him to accept humbling adages like “Your best thinking got you here.”

One night he took an overdose of Restoril, a sedative he’d been given for insomnia.

The Nardil didn’t stabilize Wallace and his psychiatrists recommended electro-convulsive therapy.

unctious

In early July, Wallace started a long second visit to Yaddo.

“The thing I like about my own prison,” he wrote Moore shortly before arriving, “is I have tenure in my prison.”

He was a dominant figure this time at Yaddo, one of the best-known writers there, with a book published and another soon to come out.

In August 1989, Girl with Curious Hair came out at last. “The stories in his first collection,” Norton’s catalog stated, “could possibly represent the first flowering of post-postmodernism: visions of the world that re-imagine reality as more realistic than we can imagine.”

He remembered his last failed attempt to get sober and how he was no longer writing and asked himself what he had to lose. He came to understand that the key this time was modesty. “My best thinking got me here” was a recovery adage that hit home, or, as he translated it in Infinite Jest, “logical validity is not a guarantee of truth.”

And now he was far clearer on why we were all so hooked. It was not TV as a medium that had rendered us addicts, powerful though it was. It was, far more dangerously, an attitude toward life that TV had learned from fiction, especially from postmodern fiction, and then had reinforced among its viewers, and that attitude was irony. Irony, as Wallace defined it, was not in and of itself bad. Indeed, irony was the traditional stance of the weak against the strong; there was power in implying what was too dangerous to say. Postmodern fiction’s original ironists—writers like Pynchon and sometimes

...more

That was it exactly—irony was defeatist, timid, the telltale of a generation too afraid to say what it meant, and so in danger of forgetting it had anything to say. For Wallace, perhaps irony’s most frightening implication was that it was user-neutral: with viewers everywhere conditioned by media to expect it, anyone could employ it to any end. What really upset him was when Burger King used irony to sell hamburgers, or Joe Isuzu, cars.

This led Wallace to conjure—easy enough since he was simultaneously already working on it—a new kind of fiction that might one day displace the Leyners of the world:

The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. The new rebels might be the ones willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the “how banal.”

His new commitment to single-entendre writing, writing that meant what it said, brought with it a surge in confidence that Wallace hadn’t felt in years, not since his 1987 visit to Yaddo.

There is no clear start date for Infinite Jest. Pieces of the novel date back to 1986, when Wallace may have written them originally as stand-alone stories. 15 The work contains all three of Wallace’s literary styles, beginning with the playful, comic voice of his Amherst years, passing through his infatuation with postmodernism at Arizona, and ending with the conversion to single-entendre principles of his days in Boston. These three approaches correspond roughly to the three main plot strands of the book: the first, the portrait of the witty, dysfunctional Incandenza family; the second, the

...more

On his first application for Yaddo, filled out in September 1986, Wallace wrote that along with “Westward” he was also working on a novel with the tentative title Infinite Jest, adding that one reason he wanted to go to the retreat was to “try to determine just where and why the stories leave off and the novel begins.”

the plot, which centers on the idea that before committing suicide James Incandenza had made a movie so absorbing that anyone who watches it succumbs to total passivity.