More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

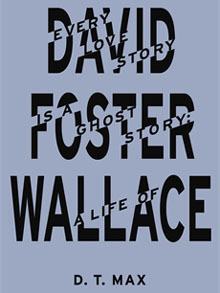

by

D.T. Max

Read between

July 7 - September 23, 2019

Brief Interviews, especially, the critic wrote, was not so much anti-ironic as “meta-ironic,” driven much like the characters in its stories by the fear of being known. This sort of writing, he continued, was clearly connected to the self-centered self-absorbed culture of late-twentieth-century America, but “does Wallace’s work represent an unusually trenchant critique of that culture or one of its most florid and exotic symptoms? Of course, there can only be one answer: it’s both.” Wallace was not pleased but he was impressed. In the margins of a draft of the story “Good Old Neon,” which he

...more

He used to tell his classes that a novelist had to know enough about a subject to fool the passenger next to him or her on an airplane;

“Good Old Neon” is the most uncomfortable of the stories in an uncomfortable volume, a narrative about an advertising executive who deliberately kills himself by crashing his car into a concrete bridge abutment. Neal is a familiar type in the Wallace world, a young man whose personality is built on the need to impress others. And the more he succeeds in impressing them, the more of a fraud he feels. Like Wallace, he feels frozen by the need to control how others see him, “condemned to a whole life of being nothing but a sort of custodian to the statue.” Suicide appears to him the only escape

...more

Karen is killing herself rehabbing the house. I sit in the garage with the AC blasting and work very poorly and haltingly and with (some days) great reluctance and ambivalence and pain. I am tired of myself, it seems: tired of my thoughts, associations, syntax, various verbal habits that have gone from discovery to technique to tic.

Learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. Because if you cannot or will not exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed. Think of the old cliché about the mind being “an excellent servant but a terrible master.”

What the novel was about was how to feel connected in your own life, and that was still the great struggle. The Web might offer a different hope of escape from the self, but actually escaping was no less futile, as those who spent their time trying discovered. (It was named the “Web” for good reason.) Among the early champions of Infinite Jest, in fact, were the technologically elite, the rising generation of information and technology experts, programmers, and webmasters, real-life counterparts to the student engineer in Infinite Jest who takes his work break on the roof of the “great hollow

...more

Chad Harbach, an editor at N+1, a literary magazine founded in Brooklyn in 2004, declared in its first issue that “David Foster Wallace’s 1996 opus now looks like the central American novel of the past thirty years, a dense star for lesser work to orbit.” It was their Catcher in the Rye, a Catcher in the Rye for people who had read The Catcher in the Rye in school. By 2006, 150,000 copies of Infinite Jest had been sold and the book continued to sell steadily.

I too have lots of stuff that’s been jostling in line inside for years for a book. And many, many pages written, then either tossed or put in a sealed box. What’s missing is some…thing. It may be a connection between the problem of writing it and of being alive. That doesn’t feel quite true for me, though. Mine is more like the whole thing is a tornado that won’t hold still long enough for me to see what’s useful and what isn’t, which tends to lead to the idea that I’ll have to write a 5,000 page manuscript and then winnow it by 90%, the very idea of which makes something in me wither and get

...more

In the summer of 2007, Wallace was eating in a Persian restaurant in Claremont with his parents and began to have heart palpitations and to sweat heavily. These can be the signs of a hypertensive crisis, although Green thinks he may have merely had an anxiety attack—the chicken and rice dish he ordered was one he had eaten many times; he never saw a doctor for a diagnosis. In any event, he eventually went to a physician, who told him what he already knew: there were a lot of superior antidepressants on the market now. Compared with them, Nardil was “a dirty drug.”

“The person who would go off the medications that were possibly keeping him alive was not the person he liked,” she says. “He didn’t want to care about the writing as much as he did.” Soon afterward, he stopped the drug and waited for it to flush out of his body. For the first weeks, he felt that the process was going well. “I feel a bit ‘peculiar,’ which is the only way to describe it,” he emailed Franzen in August, who had checked in to see how he was doing. “All this is to be expected (22 years and all), and I am not unduly alarmed. Phase 4 of

Wallace never republished “Planet Trillaphon” in a collection, probably because it was too revealing.

Containers of waste appear regularly over the years in Wallace’s writing and reach an acme in Infinite Jest. Most critics would trace the leitmotif to his affection for Pynchon, for whom waste was also a central symbol,

The passsage plays off Barth’s own essays on literature and generational conflict with their premise that the aesthetic of modernism was no longer useful and something new had to be found.

He also went to various locksmiths in Boston and explained that he was a postmodern novelist doing research on how to disarm a burglar alarm system. “Finally,” remembers Mark Costello, “the fifth didn’t throw him out.”

In Infinite Jest, Wallace traces Americans’ neediness with a Freudian touch to the original mother-infant bond. The lethal “Infinite Jest” cartridge is said to consist of a baby looking up at a mother’s face, the mother intoning, “I’m sorry. I’m so terribly sorry. I am so, so sorry. Please know how very, very, very sorry I am.”

As did others. The Onion, the satirical newspaper, ran a parody with the headline “Girlfriend Stops Reading David Foster Wallace Breakup Letter at Page 20” in February 2003, shortly before he left Bloomington.

David may have been the last great letter writer in American literature (with the advent of email his correspondence grows terser, less ambitious).