More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Joy-Ann Reid

Read between

March 16 - March 31, 2025

That blood, she believed, was on the hands of every police officer there and every police officer in Jackson. It was smeared all over Mayor Allen Thompson, who would soon express “shock” on behalf his bloodstained city. Medgar’s blood rained like a monsoon over Gov. Ross Barnett and Ole Miss and over the White Citizens’ Council and the Klan and the Sovereign Commission. Medgar’s blood stained every segregated part of Mississippi.

She buried her head in her hands, and let the tears fall. “And then,” she said, “everything became a blur.”

With that, Charles’s world seemed to collapse, all at once. Every emotion from grief to rage to guilt surged through him at the same time. And disbelief, even as Nan explained the few details she knew from her heartbreaking call with Myrlie.

Charles couldn’t help but think that had he been there, it wouldn’t have been so bad. Had he been with Medgar, they surely would have been together at that meeting and driven home together, and Charles would have been well armed and able to protect his brother from harm. None of this made sense.

His heart was drowning in grief, but his mind was full of vengeful rage.

This is the decisive battleground for America. Nowhere in the world is the idea of white supremacy more firmly entrenched, or more cancerous, than in Mississippi. —MICHAEL SCHWERNER, TWENTY-FOUR-YEAR-OLD CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST MURDERED BY MEMBERS OF THE KKK, ALONG WITH ANDREW GOODMAN AND JAMES CHANEY, BOTH TWENTY-ONE, IN MISSISSIPPI IN 1964

Myrlie Evers had to learn these rules because one wrong move, one errant word or flash of public anger, could ruin the legacy of the man she loved.

It was Myrlie Louise Evers, just three months over thirty years old, who was the first of the national civil rights widows.

‘Is he dead, Mommy?’ Reena, just eight years old asked. And I died a little as I told her that he was.”

THE MISSISSIPPI FREE PRESS, ON JUNE 15, DESCRIBED THE MOOD among Black Jacksonians as “one of deep horror and anger. Many Negroes were reported to be carrying guns.

By 11:25 A.M., all over Jackson, protesters were pouring into the streets.

Protests broke out from Los Angeles to New York to Virginia, often sparking violent reactions from police in those cities, too.

Medgar always said she was more than the wife of a civil rights leader. She was now the torch bearer representing everything he ever did or tried to do.

“I come to you tonight with a broken heart,” Myrlie said as she faced the hushed crowd. “I am left without my husband, and my children without a father, but I am left with the strong determination to try to take up where he left off. And I come to make a plea that all of you here and those who are not here will, by his death, be able to draw some of his strength, some of his courage, and some of his determination to finish this fight. Nothing can bring Medgar back, but the cause can live on. . . . We cannot let his death be in vain.”

In the months before his death, Medgar had told the Times, “If I die, it will be in a good cause,” and separately, he told the Times: “I’ve been fighting for America just as much as the soldiers in Vietnam.”

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. mourned Mr. Evers as a ‘pure patriot.’”

Roy Wilkins was spitting fire. His public statement said Medgar’s death “demonstrates anew the blind and murderous hatred which obsesses too many Mississippians. In their ignorance, they believe that by killing a brave, dedicated, and resourceful leader of the civil rights struggle, they can kill the movement for human rights. . . . Every Negro citizen has lost a valiant leader in the death of Medgar Evers. The entire nation has lost a man who believed in America and died defending its principles.”

“The cowardly ambush murder of Medgar W. Evers . . . should awaken all Americans to the plight of Negroes in Mississippi.”

“We had demonstrations defying the injunction [against public demonstrations] each day, leading up to the funeral,”

I knew that a great man, a great person that was doing God’s will, had been assassinated.”

At one point, Charles threw a polite but persistent young television reporter, Dan Rather, out of the home. “He said he’d be happy to leave the house,” Charles wrote. “But this was a big story, and he was going to be filing reports to CBS News in New York from out on the street.” Right then, Charles understood how important Medgar had become, and after that, he allowed Rather to follow him around, even confiding to Rather his murderous thoughts toward white people, to which Rather, in his Texas twang, replied, “You can’t let yourself do the same thing they did . . . not every white man is like

...more

“For one hundred years, we have turned one cheek and then the other,” he said. “And they hit us on both cheeks. Now the neck is getting tired.” And with that, he urged those in attendance to “keep on marching.”

Now, as the car turned onto Farish Street, he said to Myrlie: “Look behind you.” The massive procession was a human ocean, filling every inch of space. Many of the mourners carried American flags.

white police officers lined the side of the road, and mounted police escorted the parade of mourners, which stretched for nine full blocks.

The NAACP was now providing the security detail they had denied Medgar when he needed it most.

At the Mayflower, silent plainclothes officers lined the hallways to protect Myrlie and her children.

Now he was dead, and we were all protected.”

More than twenty-five thousand people gathered on the streets to observe the procession,61 and Myrlie observed that “block after block, there were people standing, many with heads bowed, many making the sign of the cross as we passed by. Most of them were white.”

Myrlie felt an immense pride as the car passed the Lincoln Memorial. She knew then that she had made the right decision to have Medgar buried with the full honors his country owed him—not just for serving his country, but for the stated creed of his country, and for trying to force even Mississippi to live up to it.

“My pride in Medgar had never been so great,” she wrote. “For somehow this whole experience was the final evidence that the man I had loved and married, the man whose children I had borne, was truly a great American bei...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The call lasted a long time because neither man wanted to hang up.

“I hope Medgar Evers will be the last Black American to give his life in the struggle to make the Constitution come alive.”

Roy Wilkins said Medgar had well shown that he believed in this country, but it remained to be seen if the country believed in him.

Charles could barely stand it. Growing up, Medgar so hated the cold. The thought of his little brother being lowered into the cold ground, with no way for Charles to warm his feet, like he did when they were kids and they shared a bed in Decatur—as close as if they were twins—undid him. His best friend in the world was truly gone.

The service ended with “We Shall Overcome,” the song that had prompted the Jackson police to batter young protesters during Medgar’s funeral procession.

President Kennedy had a gift for Myrlie, too: a draft copy of the civil rights bill he had promised the nation on the night before Medgar was murdered.

Kennedy handed Myrlie the draft, which he had signed for her. The bill had been sent to Congress the day before, as Medgar was being laid to rest with full military honors at Arlington.

When Myrlie, Charles, and the children arrived home on Friday, the new Jackson airport building was no longer segregated.

Beckwith,

was widely known as a vocal segregationist, Citizens’ Council member, and Klansman.

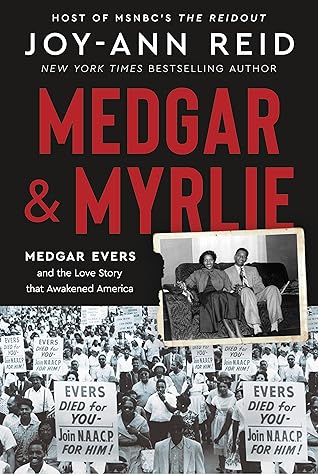

After leading 125,000 mostly Black marchers down Woodward Avenue, with many carrying signs declaring “Evers Died for You—Join NAACP for Him,” King gave an earlier version of his “I Have a Dream” speech in which he stated that “before the victory is won, some, like Medgar Evers, may have to face physical death. But if physical death is the price that some must pay to free their children and their white brothers from an eternal psychological death, then nothing can be more redemptive . . . I have a dream.” King expressed the hope “that there will be a day that we will no longer face the

...more

Myrlie said of Medgar: “He made the supreme sacrifice, gave his life for all Americans. I pray his death has shocked the complacent into active participation in achieving the goals for which he died.”

The NAACP, Dr. King, the churches, and sympathetic people of all races and faiths around the country had stepped up to raise money for the family, including funds to ensure the children would be able to attend college.

Every single night, he slept with his toy rifle, and he rarely slept through the night without nightmares.

Of the pool of nearly two hundred male potential jurors (women couldn’t serve on Mississippi juries until 1968) only a handful were Black, and they were systematically excluded by the defense. After four days of selection, the jury consisted, as was the Mississippi way, of twelve white men.

Myrlie was being called as a witness, and when she asked how she would be addressed in court, Waller dismissively told her not to expect to be called “Mrs.” or “Ms.” She was in Mississippi, after all.

On July 2, which would have been Medgar’s thirty-ninth birthday, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law.

I have learned over the years that when one’s mind is made up, this diminishes fear; knowing what must be done does away with fear. —ROSA PARKS

America was continuing to indulge its habit of murdering the men who strove to save the country from, as King warned, going to Hell.

Charles Evers said he became close to Bobby, whom he called “his best friend in the world” after Medgar.