More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

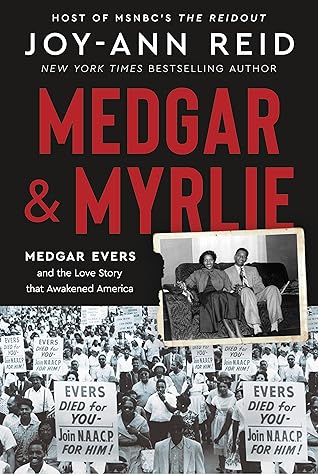

Joy-Ann Reid

Read between

March 16 - March 31, 2025

It is not just about the love between two Black people in Mississippi, and their love for their children. It is also about the higher love it took for Black Americans to love America and to fight for it, even in the state that butchered more Black bodies via lynching than any other, and that ripped apart the promise of Reconstruction with a ferocity unmatched by any other place in this fragile and fractured nation.

Myrlie Evers demanded more than once that Medgar tell her if he loved her and his children more than his work. He pressed her to understand that he did his work because he loved her and their children.

He was determined to exorcise the ghosts in the trees that whispered to him and his brother that in Mississippi, and throughout America, people like them were something less than human. Medgar’s work was a labor of love.

Lincoln’s words on the plaque were published in Harper’s Weekly in July 1865, three months after his assassination: “I have been driven many times to my knees by the overwhelming conviction that I had nowhere else to go. My own wisdom, and that of all about me, seemed insufficient for that day.”

he possessed “the calm of someone who knows they’re going to die before their time—like Martin Luther King.”

King and his deputies were galvanized by the Evers killing as they planned an August March on Washington, at which Myrlie Evers was to be among the few women slated to speak.

He was a World War II veteran and a human being. Yet the moment he returned to Mississippi he was nothing but a nigger.

The trouble started as soon as they got close to his hometown. “When we were almost there, the driver asked me to move . . . to the back. Well, I wouldn’t do it,” he said. “Hell, I’d just been on a battlefield for my country. When we reached my hometown, the driver signaled to some men in town. They came on the bus and beat me within an inch of my life.” Medgar actually told the story laughing. “It was the worst beating I ever had,” he said. “But after that, I was a different man.”

He told the story again and again. He just couldn’t let it go.

“It didn’t take much reading of the Bible,” he said, “to convince me that two wrongs would not make the situation any different, and that I couldn’t hate the white man and at the same time hope to convert him.”

He dreamed of becoming a lawyer and combatting the discrimination against Black Mississippians in the courts.

Medgar’s military service gave him confidence and perspective, and it heightened the contradictions between the mission of fighting for liberty and freedom abroad, while at home as a Negro man he had none.

He had a girl, whose family accepted him. He could have a life outside Decatur and racist Mississippi. It was a temporary dream.

He wrote to Charles that he saw no reason they should have to leave Mississippi in order to succeed. He wanted to put his foot down in his home state and raise Black children in freedom there.11

“This is home,” he later said. “Mississippi is a part of the United States. And whether the Whites like it or not, I don’t plan to live here as a parasite. The things that I don’t like I will try to change. And in the long run, I hope to make a...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

MEDGAR, CHARLES, AND THEIR SIBLINGS HAD RECEIVED THE standard education of every Black Southern child—the realization that there were three kinds of white people: the ones who hated you but were too cowardly to do anything about it, the dangerous ones who would kill you just as soon as look at you, and the nice-acting ones who despite their kindness wouldn’t do a damned thing about it.

(Mississippi juries were of course, all white, and until 1968 all male);

Your life was in danger every minute of every day. You lived at the whim of any white person’s momentary moods.

Slavery hadn’t really ended for the sharecroppers still tied to white planters’ land and for those trapped in the pernicious system of convict leasing that thrived in the loophole of the Thirteenth Amendment.

The white plantation owners who ran every rural Southern town closed the Negro schools during planting season so Black children could pick cotton in their fields.

When Medgar and Charles made the miles-long trek to the ramshackle, one-room, all-Black school during the nonplanting season on foot, “white kids in their school buses would throw things at us and yell filthy things.” Medgar called this the “elementary course” in white supremacy.

Life was humiliation and threat, every day, all day. Slavery was technically gone, but the plantation class was determined to cling to as many of its social and economic features as possible, using every cruel means they could find.

Charles wrote that Medgar asked their father afterward why those men killed Mr. Tingle. The answer had to be as devastating to a young Black psyche as the murder itself: “just because he was a colored man.” When Medgar asked his dad if white men could kill him, too, Mr. Evers told them the truth: “If I was doing anything they didn’t like, they sure could kill me.”

Jessie Wright Evers ensured her children went to school every day, all four months of the Negro school year.

Bilbo ended the speech with a menacing flourish: “The best way to keep a nigger away from a white primary in Mississippi,” he said, “is to see him the night before.”

“I had been on Omaha Beach,” Medgar told reporters years later. “All we wanted was to be ordinary citizens. We fought during the war for America—and Mississippi was included. Now after the Germans and the Japanese hadn’t killed us, it looked as though the white Mississippians would.”

Medgar quickly discovered firsthand the abuses and indignities the sharecroppers in the Delta suffered, often leaving them barely better off than their grandparents had been during slavery. He lamented to Myrlie that these sharecroppers “might as well be slaves.”

they returned it, saying it lacked a second reference from a white citizen who’d known Medgar for ten years.

The goal of seemingly every public policy in the South, and especially in Mississippi, as Medgar described it in his first report as NAACP field secretary in December 1954, was to keep “the Negro in his place . . . keep him out of white schools . . . keep the ballot out of his reach . . . [and] keep him dependent” 13 even though Black Mississippians comprised the majority in a number of counties, particularly in the Delta.

The report noted that Mound Bayou had “19,000 whites and 46,000 Negroes, and of course Bolivar County,” where Mound Bayou sat, “has one of the strongest [White Citizens’] councils in the Delta.”

M’dear’s stories brought into sharp relief the ravages and dangers of being a Black girl and woman in a society built on the bedrock of slavery, a world in which the men in your life—your father, your brothers, and your husband—had no power to protect you from the whims of predatory white men, from violence or rape, or from daily humiliation.

“He was on his way to where? To the courthouse, to deliver some absentee ballots. And at 10:00 A.M. in the morning . . . broad open daylight,” he was shot dead. “What was his crime? He just wanted to be enfranchised. He just wanted to exercise his constitutional right to vote.”

A frenzy was growing among white Mississippians to stop the train of integration at whatever bloody cost.

Mamie channeled Rosebud Lee in insisting that the remains of her once-beautiful boy be on display in an open casket, so that the whole world had to reckon with what the State of Mississippi had done to him, through the hands of those soulless

Bishop Louis Ford used his eulogy to call on President Eisenhower to “go into the Southern states and tell the people there . . . that unless the Negro gets full freedom in America, it is impossible for us to be leaders in the rest of the world.”

When the all-white male jury acquitted both men after just ninety minutes of deliberation on September 23, with the predetermined outcome delayed only “to drink pop,” the outrage was electric, and global.

Under Medgar’s tutelage, Brown organized the first NAACP Youth Council in Mississippi that fall, in September 1955, the same month Milam and Bryant were acquitted.

The Youth Councils would become the bedrock of the civil rights movement in Mississippi, and its primary source of young activists.

Rosa Parks, already an NAACP activist, was there that night, and she later said the Emmett Till case gave her the strength to remain in her front seat in the bus,

Eight years later, King and his associates fixed the date of the March on Washington on the anniversary of Till’s slaying—August 28, 1963.

Sweet Owens’s mother informed her and her brother that the “nice white lady” and her family were moving away. The woman had told Mrs. Sweet, “We have to move because of integration. It’s coming.”

At the commission’s behest, white newspapers published the names of anyone who attended a civil rights meeting, making them vulnerable to retribution from their employer or mortgage holder, likely Citizens’ Council members or, worse, from the Klan.

the only Black congressman from exquisitely gerrymandered Mississippi.

King’s friendship with Medgar evolved quickly. “I think he considered me a student. But it was more like I was a little brother that could be guided. And I vaguely understood [that] for him to trust a white man was not something to be taken for granted.”

The Sovereignty Commission conducted a thorough investigation of Kennard’s background and were unable to produce anything it could use to reject his application. They needed a new tactic.

Kennard was arrested by state police and charged with stealing $25 worth of chicken feed from the county co-op that police had planted on his farm.

Mississippi’s notorious “pig law,” passed in 1876, made such a theft punishable as an act of grand larceny with sentences of up to five years.

The law led to the imprisonment of thousands of impoverished, formerly enslaved men and quadrupled Mississippi’s prison population.

Not uncoincidentally, the profits from working convicts at plantation prisons like Parchman State Penitentiary, and the leasing of convicts as free labor to local planters, effectively returned slavery to the state, bringing...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Now, the Citizens’ Councils and Sovereignty Commission were weaponizing those l...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.