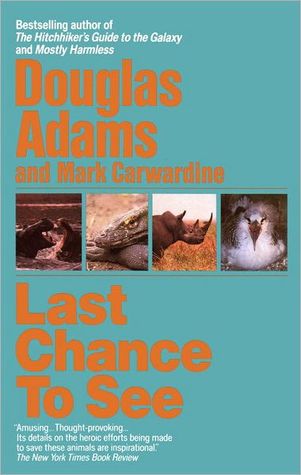

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

When Madagascar sheered off into the Indian Ocean, it became entirely isolated from all the evolutionary changes that took place in the rest of the world. It is a life raft from a different time. It is now almost like a tiny, fragile, separate planet.

Virtually everything that lives in the Madagascan rain forest doesn’t live anywhere else at all, and there’s only about ten percent of that left. And that’s just Madagascar.

“One species after another is on the way out. And they’re really major animals. There are less than twenty northern white rhino left, and there’s a desperate battle going on to save them from the poachers. They’re in Zaïre. And the mountain gorillas too—they’re one of man’s closest living relatives, but we’ve almost killed them off this century. And it’s happening throughout the rest of the world as well.

“The kakapo. It’s the world’s largest, fattest, and least-able-to-fly parrot. It lives in New Zealand. It’s the strangest bird I know of and will probably be as famous as the dodo when it goes extinct.”

“There are,” said Mark, “more poisonous snakes per square metre of ground on Komodo than on any equivalent area on earth.”

“The Indian cobra is the fifteenth deadliest snake in the world, and all the other fourteen are here in Australia.

The most poisonous spider is the Sydney funnel web.

Until relatively recently—in the evolutionary scale of things—the wildlife of New Zealand consisted of almost nothing but birds. Only birds could reach the place. The ancestors of many of the birds that are now natives of New Zealand originally flew there. There was also a couple of species of bats, which are mammals, but—and this is the point—there were no predators. No dogs, no cats, no ferrets or weasels, nothing that the birds needed to escape from particularly.

The kakapo is a bird out of time. If you look one in its large, round, greeny-brown face, it has a look of serenely innocent incomprehension that makes you want to hug it and tell it that everything will be all right, though you know that it probably will not be.

I can remember once coming face to face with a free-roaming emu years ago in Sydney zoo. You are strongly warned not to approach them too closely because they can be pretty violent creatures, but once I had caught its eye, I found its irate, staring face absolutely riveting. Because once you look one right in the eye, you have a sudden sense of what the effect has been on the creature of having all the disadvantages of being a bird—absurd posture, a hopelessly scruffy covering of useless feathers, and two useless limbs—without actually being able to do the thing that birds should be able to

...more

one of the more dangerous animals in Africa is, surprisingly enough, the ostrich. Deaths due to ostriches do not excite the public imagination very much because they are essentially so undignified. Ostriches do not bite because they have no teeth. They don’t tear you to pieces because they don’t have any forelimbs with claws on them. No, ostriches kick you to death. And who, frankly, can blame them?

“There’s an island near here—a very, very important island as far as wildlife is concerned—called Round Island. There are more unique species of plants and animals on Round Island than there are on any equivalent area on earth. About a hundred, hundred and fifty years ago, somebody had the bright idea of introducing rabbits and goats to the island so if anybody got shipwrecked there, they’d have something to eat.

a quotation from Mark Twain, which read, “You gather the idea that Mauritius was made first and then heaven; and that heaven was copied after Mauritius.” “That was less than a hundred years ago,” said Richard. “Since then just about everything that shouldn’t be done to an island has been done to Mauritius. Except perhaps nuclear testing.”

the eight bottle palm trees on Round Island are the only ones to be found in the wild anywhere in the world?

the Hyophorbe amaricaulis (a palm tree so rare that it doesn’t have any name other than its scientific one) standing in the Curepipe Botanic Gardens in Mauritius is the only one of its kind in existence?

None of us will ever see this bird though, because, sadly, the last one was clubbed to death by Dutch colonists in about 1680. The giant tortoises were eaten to extinction because the early sailors regarded them much as we regard canned food. They just picked them off the beach and put them on their ships as ballast, and then, if they felt hungry, they’d go down to the hold, pull one up, kill it, and eat it. But the large, gentle dove—the dodo—was just clubbed to death for the sport of it. And that is what Mauritius is most famous for: the extinction of the dodo.

Up until that point it hadn’t really clicked with man that an animal could just cease to exist. It was as if we hadn’t realised that if we kill something, it simply won’t be there anymore. Ever. As a result of the extinction of the dodo, we are sadder and wiser.

With cuttings from this one plant, botanists at Kew Gardens are currently trying to root and cultivate two new plants, in the hope that it might then be possible to reintroduce them into the wild. Until they succeed, this single plant standing within its barbed-wire barricades will be the only representative of its species on earth, and it will continue to need protecting from everyone who is prepared to kill it in order to have a small piece.

conservation is very much in tune with our own survival. Animals and plants provide us with life-saving drugs and food, they pollinate crops and provide important ingredients for many industrial processes. Ironically, it is often not the big and beautiful creatures, but the ugly and less dramatic ones, that we need most.

There is one last reason for caring, and I believe that no other is necessary. It is certainly the reason why so many people have devoted their lives to protecting the likes of rhinos, parakeets, kakapos, and dolphins. And it is simply this: the world would be a poorer, darker, lonelier place without them.