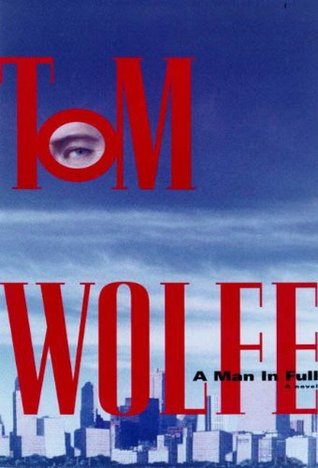

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

What the hell had happened to all these sons of the rich in Wally’s generation, these well-brought-up boys who went off to the private schools? These damned schools were producing a new kind of scion of the elite: a boy utterly world-weary by the age of sixteen, cynical, phlegmatic, and apathetic around adults, although perfectly respectful and maddeningly polite, a boy inept at sports, averse to hunting and fishing and riding horses or handling animals in any way, a boy embarrassed by his advantages, desperate to hide them, eager to dress in backward baseball caps and homey pants and other

...more

Conrad had sunk back into Book III of Epictetus … Will you realize once and for all that it is not death that is the source of a mean and cowardly spirit but rather the fear of death? Against this fear then I would have you discipline yourself—

“Landor was a good poet, but not a great one. He was too polite, too proper, too staid, too content with the comfort of what he already had to take a chance on his very best. How old are you?”

Epictetus says, “Your poor body, then, is it slavish or free?” One of his students says, “We know not.” “Do you not know that it is a slave to fever, gout, ophthalmia, dysentery, the tyrant, fire, sword, everything stronger than itself?” “Yes, it is a slave.” “How then can any part of the body be still free from hindrance? How can that which is naturally dead—earth and clay—be great or precious? What then? Have you no element of freedom?” “Perhaps none.” “Why, who can compel you to assent to what appears false?” “No one.” “And who to refuse assent to what appears true?” “No one.” “Here, too,

...more

“To a Stoic there are no dilemmas. They don’t exist.”

“Epictetus talks about exactly that, Mr. Croker. He says, ‘You’re not afraid of starving, you’re afraid of losing face.’ He says, ‘You don’t have to have some high position before you can be a great man.’ One of the great Stoic philosophers, Cleanthes, hauled water to make a living. He was a day laborer, Mr. Croker. But nobody thought of him as someone who didn’t have a respectable job.

‘You have priceless silver and goblets of gold,’ said the philosopher, ‘but your reason is of common clay.’

“What say you, fellow? Imprison me? My bit of a body you will imprison—yes, but my will—no, not even Zeus can conquer that.”

“Like the bull, the man of noble nature does not become noble all of a sudden; he must train through the winter and make ready.”