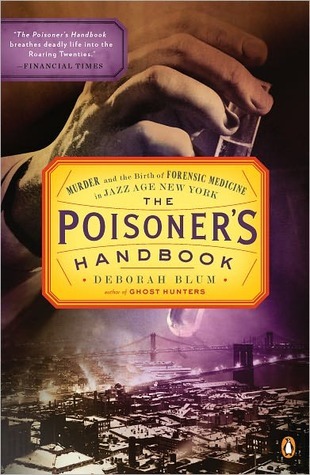

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Deborah Blum

Read between

June 30 - July 3, 2022

CYANIDES POSSESS a uniquely long, dark history, probably because they grow so bountifully around us. They flavor the leaves of the yew tree, the flowers of the cherry laurel, the kernels of peach and apricot pits, and the fat pale crunch of bitter almonds. They ooze in secretions of arthropods like millipedes, weave a toxic thread through cyanobacteria, massed in the floating blue-green algae along the edges of the murkier ponds and lakes, and live in plants threaded through forests and fields.

Liong and 1 other person liked this

In early 1930 the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company reported that deaths due to alcoholism were now 600 percent higher (among its 19 million policyholders) than those tallied in 1920, the first year that consumption of alcohol was prohibited. These statistics suggested that Prohibition had fostered a nation of heavy drinkers and that the habit was killing thousands of people.

Arguably the three most important atoms on Earth are carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen. Carbon provides the fundamental chemical base of every life-form on the planet, past and present. When fuels derived from the decomposed and fossilized life of the past—such as coal or gasoline—burn, they release carbon into the air. Oxygen is vital to keeping carbon-based life forms alive, barring a few odd creatures like anaerobic bacteria. And if two hydrogen atoms attach to a single oxygen atom, the result—H2O—is that gloriously necessary liquid called water.

One of the most provocative, published in 1908, was a study of rats and rabbits that were provided a regular supply of ethyl alcohol. After the scientists had created a colony of alcoholic animals, they offered the same laboratory cocktails to animals with no previous exposure. The novice drinkers became stumbling drunk on the same amount of alcohol that no longer had any effect on the habituated rats and rabbits. By doing a series of blood draws, the scientists found that their habitués had somehow learned to better process their drinking binges. The unaccustomed animals absorbed 20 percent

...more

Essentially, the Gettler and Freireich study showed how the body of a habitual drinker adjusted, became more efficient in metabolizing ethyl alcohol. The liver generated more enzymes to break the alcohol down. More liquor was processed out, so less entered the bloodstream. It thus took longer for an intoxicating amount to accumulate and reach the brain. That wasn’t pure good news. Chronic drinkers needed to take in more alcohol, sometimes a lot more, to reach the level in the brain that produced intoxication. They usually responded by drinking