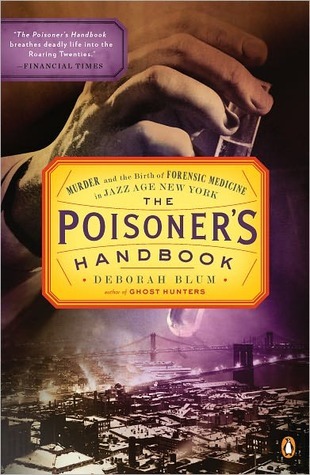

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Deborah Blum

As a result murder by poison flourished. It became so common in eliminating perceived difficulties, such as a wealthy parent who stayed alive too long, that the French nicknamed the metallic element arsenic poudre de succession, the inheritance powder.

One exasperated French prosecutor, during a mid-nineteenth-century trial involving a morphine murder, exclaimed: “Henceforth let us tell would-be poisoners; do not use metallic poisons for they leave traces. Use plant poisons . . . Fear nothing; your crime will go unpunished. There is no corpus delicti [physical evidence] for it cannot be found.”

The 1896 book Medical Jurisprudence, Forensic Medicine and Toxicology, cowritten by a New York research chemist and a law professor, documented the still-fierce competition between scientists and killers.

IN 1918, HOWEVER, New York City made a radical reform that would revolutionize the poison game and launch toxicology into front-page status. Propelled by a series of scandals involving corrupt coroners and unsolved murders, the city hired its first trained medical examiner, a charismatic pathologist by the name of Charles Norris. Once in office, Norris swiftly hired an exceptionally driven and talented chemist named Alexander Gettler and persuaded him to found and direct the city’s first toxicology laboratory. Together Norris and Gettler elevated forensic chemistry in this country to a

...more

Infanticide, for instance, was almost never punished.

The city required no medical background or training for coroners, even though they were charged with determining cause of death.

As a result, Wallstein found, death certificates were filled out with no effort at determining cause. Among the entries were “could be suicide or murder,” and “either assault or diabetes.”

The term methyl was derived from the Greek methy (meaning wine) and hyle (meaning wood, or, more precisely, patch of trees).

Another groggy patron wrote, about a night of clubbing: the bartender “brought me some Benedictine and the bottle was right. But the liqueur was curious—transparent at the top of the glass, yellowish in the middle and brown at the base . . . Oh, what dreams seemed to result from drinking it . . . That is the bane of speakeasy life. You ring up your friend the next morning to find out whether he is still alive.”

There was the Bennett Cocktail (gin, lime juice, bitters), the Bee’s Knees (gin, honey, lemon juice), the Gin Fizz (gin, lemon juice, sugar, seltzer water), and the Southside (lemon juice, sugar syrup, mint leaves, gin, seltzer water).

Scholars have found references to “death by peach” in Egyptian hieroglyphics, leading them to believe that those long-ago dynasties carried out cyanide executions, perhaps by making a potion from poisonous fruit pits.

The duo were endlessly inventive in procuring illegal offerings. Smith had once jumped into icy water so that Einstein could rush him into a bar and beg a drink for a freezing man. They then busted the bar. They had posed as football players (when arresting an ice cream vendor who sold gin out of his cart), Texas Rangers, a Yiddish couple (Smith playing the wife), streetcar conductors, gravediggers, fishermen, and ice men. Einstein—who had a booming baritone—once introduced himself as an opera singer and gave a rousing performance in a speakeasy before closing it down.

Gettler wrote in the American Journal of Clinical Pathology

A 1938 paper, “The Toxicology of Cyanide,”

Lucretia and Cesare Borgia, feared in fifteenth-century Italy for their ruthless mixture of politics and poison.

Rudolph Witthaus, coauthor of the massive 1896 tome Medical Jurisprudence, Forensic Medicine and Toxicology

In 1872, one notorious British murderer, Mary Ann Cotton, killed fifteen people, including all the children of her five husbands, and several neighbors who irritated her, before she was caught in 1872, tried, and hanged.

Even worse for those who hope to avoid detection, arsenic tends to slow down the natural decomposition of human tissue, often creating eerily well-preserved corpses. Toxicologists refer to this effect as arsenic “mummification.”