More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

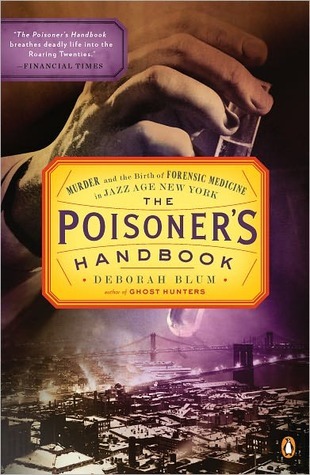

by

Deborah Blum

Read between

December 6 - December 11, 2022

At the turn of the twentieth century, the British Medical Association called chloroform the most dangerous anesthetic known, and the American Medical Association urged that hospitals stop using it entirely. But it would be several more decades before chloroform disappeared from the pharmacy shelves.

Coroners had other sources of income as well. They sold fake death certificates and thereby covered up murders, criminal abortions, and suicides.

The city required no medical background or training for coroners, even though they were charged with determining cause of death.

A few death certificates simply read “act of God.”

Alcoholics, with their often damaged livers, were among those most quickly killed by chloroform;

“This work, which I may term ‘organization,’ ” has apparently not been tried before, Norris wrote to Hylan, displaying his contempt for the previous system.

The conversion to the “more dangerous poisons” can take up to five days, meaning that the wood alcohol drinker can stew in an increasingly lethal cocktail for the better part of a week.

Schools remained open,

“One teaspoon of wood alcohol is enough to cause blindness,” Norris warned.

“Prohibition is a joke. It has deprived the poor workingman of his beer and it has flooded the country with rat poison.”

They created a new generation of cocktails heavy on fruit juices and liqueurs to mix with the bathtub gin, bright and spicy additions to cover the raw sting of the spirits.

They flavor the leaves of the yew tree, the flowers of the cherry laurel, the kernels of peach and apricot pits, and the fat pale crunch of bitter almonds.

Scholars have found references to “death by peach” in Egyptian hieroglyphics, leading them to believe that those long-ago dynasties carried out cyanide executions, perhaps by making a potion from poisonous fruit pits.

Within two to five minutes after ingestion of the poison, the individual collapses, frequently with a loud scream (death scream).”

poisoners were hard to catch and even harder to convict.

The animal studies—later confirmed in analyses of human cyanide victims—showed that the poison is absorbed differently depending on how it is taken.

Physicians often mistook symptoms of arsenic poisoning for natural diseases,

But a chemical vulnerability is built into it, which becomes very apparent with exposure to a poison such as cyanide or carbon monoxide. Both poisons attach to hemoglobin far more effectively than oxygen.

The government knows it is not stopping drinking by putting poison in alcohol. It knows what the bootleggers are doing with it and yet it continues its poisoning processes, heedless of the fact that people determined to drink are daily absorbing that poison. Knowing this to be true, the United States Government must be charged with the moral responsibility for the deaths that poisoned liquor causes, although it cannot be held legally responsible.

But they weren’t accustomed to having their national government adopt a policy known to kill people in droves. In the offices at Bellevue, their outrage crackled like a current in the air.

More than anyone else, the city’s impoverished residents were paying the real price of Prohibition.

The lethal undiluted dose was as little as two teaspoons for a child, perhaps a quarter cup for an adult man. That modest amount, far too often, was a direct path to blindness, followed by coma, followed by death.

Rumor had it that her husband, Pierre, killed in 1906 by a horse-drawn carriage, had stumbled into the street due to radiation-induced weakness.

medical examiners should never be swayed by politicians.

In early 1930 the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company reported that deaths due to alcoholism were now 600 percent higher (among its 19 million policyholders) than those tallied in 1920,

Ethyl alcohol, by contrast, dissolves rather easily into acetic acid, the bitter but basically harmless compound that is the primary constituent in vinegar, and the acid breaks down further into carbon dioxide and water.

The answer had to lie in the correlation between alcohol levels in the blood and in the brain: how much meant cheerful intoxication, and how much meant falling-down drunk?

By the end of the 1920s, researchers knew that tobacco smoke contained more than nicotine and carbon monoxide. They’d also found cyanide, hydrogen sulfide, formaldehyde, ammonia, and pyridine, the latter a component in industrial solvents.

The manager of Louis Sherry’s, the stylish two-story restaurant at 300 Park Avenue, worried that customers would have to relearn the appropriate wine for each course.

citizens had become test animals for chemical industries that were indifferent to their customers’ well-being.

Arsenic killers were often so successful with their first murder that they tended to believe they could get away with it again.

This dramatic shift in popular opinion was made possible by Norris’s and Gettler’s unfaltering dedication to furthering the study of forensic toxicology. Norris’s and Gettler’s often thankless work—the long nights in the laboratory, the endless fights with the mayor’s office, the battles against the federal government and big business alike—had produced real results. Norris and Gettler had, indeed, changed the poison game.