More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“The example of our revolution and the lessons it implies for Latin America have destroyed all the coffeehouse theories: we have demonstrated that a small group of men supported by the people and without fear of dying were it necessary can overcome a disciplined regular army and defeat it.

Che’s speech was nothing less than a siren call to the hemisphere’s would-be revolutionaries and an implicit declaration of war against the interests of the United States.

Che had not been looking or feeling well for some time. He was gaunt and his eyes were sunken. Ill health was one of the reasons he hadn’t accompanied Fidel to Venezuela, where he had been invited to speak by a medical society, but it wasn’t until March 4 that he took a break in his schedule and allowed doctors to X-ray him. He was diagnosed with a pulmonary infection and told that he had to convalesce. He was also told to stop smoking cigars. Che, who had became addicted to tobacco during the war, persuaded the doctors to allow him one tabaco a day. The patient interpreted this rule

...more

The 1959 sugar harvest season had begun, and Che suggested reducing the working day from eight to six hours to create more jobs. Menéndez pointed out that this would set off a wave of similar work-reduction demands throughout the Cuban labor market, increase the cost of sugar production, and affect Cuba’s profits on the world market. “You may be right,” Che replied. “But, look, the first mission of the revolution is to resolve the unemployment problem in Cuba. If we don’t resolve it, we won’t be able to stay in power.”

He insisted that Menéndez give him a proposal on reducing the workday, but in the end Fidel quashed the idea.

The universities were alarmed about Fidel’s apparent lack of regard for the hallowed tradition of academic autonomy, and a crackdown on press freedoms seemed likely.

Che found that part of his entourage had vanished. When asked where the men were, Menéndez told Che he didn’t know. “They’re out whoring, aren’t they?” Che said. Menéndez insisted he really didn’t know, and Che seemed to relent. “I know what it’s like to putear,” he said. “I whored round in my youth, too.”

Then, as always with his mother, he became introspective.

Something which has really developed in me is the sense of the collective in counterposition to the personal; I am still the same loner that I used to be, looking for my path without personal help, but now I have a sense of my historic duty. I have no home, no woman, no children, nor parents, nor brothers and sisters, my friends are my friends as long as they think politically like I do and yet I am content, I feel something in life, not just a powerful internal strength, which I always felt, but also the power to influence others, and an absolutely fatalistic sense of my mission, which strips

...more

You have arrived, you’re an emissary of the Kremlin, and we can say that we now have relations. But we can’t tell this yet to the [Cuban] people. The people aren’t ready, they have been poisoned by the bourgeois American propaganda to be against Communism.”

Fidel cited Lenin on the revolutionary strategy of “preparing the masses”—telling Alexiev he was going to heed the dictum; he would eradicate the anticommunist press campaign and, gradually, the people’s prejudices, but he needed time.

Until then, Alexiev had harbored a skeptical view of Fidel, but the evidence that he had read Lenin (“not too deep...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Alexiev continued probing to ascertain how much Fidel’s conception of his revolution matched or differed from Che’s. “It’s a true revolution,” Fidel told him, “made by the people and for the people. We want to build a just society without man exploiting his fellow man, and with an armed people to defend their victories. If Marx were to arise now he would be pleased to see me giving arms to the people.” Although Alexiev noted that Fidel avoided using the word “socialism,” whereas Che had used it, Fidel “made it understood” that they shared the same philosophy.

In January 1959, and again in April, Che had talked about Cuba’s need to nationalize its oil and mineral wealth. In September 1959, Fidel said this was an issue that needed to be “carefully studied.” Nine months later, he would seize the refineries owned by Texaco, Esso, and British Shell.

In November 1959, the U.S. embassy noted a recent interview with Che in Revolución, which made plain that “regardless of what the Agrarian Reform Law may say about making the peasants small property owners, as far as Guevara is concerned, reform will be aimed more in the direction of cooperatives or communies [sic].” Three months after the interview, in January 1960, Fidel issued a decree seizing all sugar plantations and large cattle ranches and making them state-run cooperatives.

October 1959 had been a particularly crucial time. By the end of the month, the stage had been set for what Hugh Thomas has called the “eclipse of the liberals” and the final ascendancy of the anti-American, “radical” wing of the revolution. The course long advocated by Che was now being steered, more and more openly, by Fidel himself.

Che carried the same message to Cuba’s second university, in Santiago, where he bluntly announced that university autonomy was over. Henceforth the state would design the curriculum. Central planning was necessary, Cuba was going to industrialize, and it needed qualified technicians—agronomists, agricultural teachers, and chemical engineers—not a new crop of lawyers.

“Who has the right to say that only 10 lawyers should graduate per year and that 100 industrial chemists should graduate?” Che asked. “Some would say that that is dictatorship, and all right: it is dictatorship.”

“The University, he said, “must paint itself black, mulatto, worker and peasant.” If it didn’t, he warned, the people would break down its doors “and paint the University the colors they like.”)

In Pinar del Río, a sugar mill had been bombed by an unidentified plane and a group of suspected rebels that included two Americans had been captured. At

Fidel had dubbed 1960 “The Year of Agrarian Reform,” but a better label might have been “The Year of Confrontation.” The month leading up to Mikoyan’s visit in February saw a rapid deterioration in U.S.-Cuban relations and an open acceleration of Cuba’s “socialization.” A tit-for-tat war began in early January with a note of protest sent by Secretary of State Herter over the “illegal seizures” of American-owned property, for which no compensation had been paid. Cuba responded by seizing all the large cattle ranches and all sugar plantations in the country, including those owned by Americans.

...more

The Soviet trade fair in February turned out to be a great success. More than 100,000 Cubans visited during a period of three weeks. They viewed the Sputnik replica; the models of Soviet homes, factories, and sports facilities; the tractors and displays of farm and industrial equipment. These were the technological achievements of the nation that Nikita Khrushchev had told Americans would “bury” them in the not too distant future. To the average untraveled Cuban in early 1960, such claims were credible. After all, hadn’t Russia been the first country to put a satellite—even a live dog—into

...more

Throughout Mikoyan’s stay, nocturnal attacks on Cuban sugar mills and cane fields by small planes based in the United States continued without letup. In late February, one of the marauding planes crashed on Cuban soil, killing its occupants, and the identity papers of one of the dead showed him to be a U.S. citizen. Fidel cited this as evidence of U.S. complicity in the attacks. When CIA Director Dulles informed Eisenhower that the dead man and those piloting the other sabotage missions were in fact CIA hire-lings, Eisenhower quietly urged Dulles to come up with a more comprehensive plan to

...more

Sergo Mikoyan accompanied his father on most of his peregrinations around the island and was able to observe Cuba’s leaders closely. Right away, he noticed the difference between Che and Fidel. He had read about Che, and he recalled that he had expected to meet a “manic guerrilla,” a kind of fire-eating Latin American Bolshevik, but Che didn’t fit the image.

“I now saw a man who was very silent, with very tender eyes,” Sergo said. “You feel a little distance when you talk with Fidel [because] ... he almost doesn’t listen to you, but with Che one didn’t feel that. Although I had expected him to be the obstinate one, I realized he wasn’t stubborn, but inclined to talk, to discuss, and to listen.”

“It was a very strange chat,” Sergo Mikoyan said. “They told [my father] that they could survive only with Soviet help, and they would have to hide the fact from the capitalists in Cuba. ...

[Then] Fidel said, ‘We will have to withstand these conditions in Cuba for five or ten more years,’ at which Che interrupted and told him: ‘If you don’t do it within two or three years, you’re finished.’ There was this difference [of conception] between them.”

Fidel then launched into a soliloquy about how the rebels’ victory had proved Marx wrong. “Fidel said that according to Marx, the revolution could not have happened except along the paths proposed by his Communist Party and our Communist Party. ... Mass struggle, strikes, and so forth. ‘Bu...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

My father contradicted him. He said, ‘You think this way because your Communists are dogmatic; they think Marxism is just A, B, C, and D. But Marxism is a way, not a dogma. So I don’t think you have proven Mar...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

It was carnage. Up to 100 people had been killed—mostly stevedores, sailors, and soldiers—and several hundred others had been injured. La Coubre was loaded with Belgian weapons, and somehow the cargo had ignited. Fidel accused the CIA of sabotage.

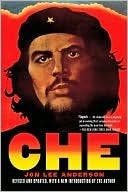

one point, Che appeared and Korda shot two frames of him silhouetted against the sky. The photographs of Che weren’t used by Revolucíon for its account of the event, but Korda cropped a palm tree and another figure out of one of them and printed it for himself and pinned it to the wall of his studio. He would occasionally give copies to friends and other visitors. (In April 1967, he gave two prints to the left-wing Italian publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who turned them into thousands of copies of a poster, the first large-scale use of what would become one of the most famous images of the

...more

Upon being notified of Fidel’s rebuff, Eisenhower approved the CIA’s plan to covertly recruit and train an armed force of several hundred Cuban exiles to lead a guerrilla war against Castro. CIA Director Dulles planned to model the operation after the aptly named Operation Success, the undermining of the Arbenz regime in Guatemala in 1954.

When Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre visited Cuba in February, the famous French couple went to see Che, and they talked for hours. It must have been a very gratifying experience for him, playing host to the philosopher whose works he had grown up reading.

For his part, Sartre came away extremely impressed. When Che died, Sartre wrote that he was “not only an intellectual but also the most complete human being of our age.”

Che talking to Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, who visited him on their trip to Cuba in 1960. Antonio Nuñez Jiménez is at left.

De Beauvoir was bewitched by the sensual, fervent mood.

“Young women stood selling fruit juice and snacks to raise money for the State,” she wrote later. “Well-known performers danced or sang in the squares to swell the fund; pretty girls in their carnival fancy dresses, led by a band, went through the streets making collections. ‘It’s the honeymoon of the Revolution,’ Sartre said to me. No machinery, no bureaucracy, but a direct contact between leaders and people, and a mass of seething and slightly confused hopes. It wouldn’t last forever, but it was a comforting sight.

For the first time in our lives, we were witnessing happiness that had been...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Fidel also took up the gauntlet Che had thrown to the American oil companies. They would do as Cuba requested and process the Soviet oil, he declared, or face the confiscation of their properties. Days later, Cuba expelled two U.S. diplomats, accusing them of spying; in response, the Americans expelled three Cuban diplomats.

The war of wills quickly escalated. Fidel warned the United States that it ran the risk of losing all its property in Cuba.

On July 3, the U.S. Congress authorized President Eisenhower to cut Cuba’s sugar quota. Fidel responded by legalizing the nationalization of all American property in Cuba.

In Cuba, he said, they had done what had to be done. They had used the paredón—the firing squad—and chased out the monopolies, in spite of those who preached moderation, most of whom, he said, had turned out to be traitors anyway. “‘Moderation’ is another one of the terms the colonial agents like to use,” Che said. “All those who are afraid, or who are considering some form of treason, are moderates. ... But the people are by no means moderate.”

As the U.S. presidential election entered its final stretch, the fencing between Washington and Havana accelerated. Cuba had become a central issue in the campaign, with each of the candidates—Vice President Nixon and Senator Kennedy—promising to be tougher against Cuba than his opponent would be.

Kennedy ridiculed the Eisenhower administration’s “do-nothing” policies that had brought about the present crisis; his administration, he said, would take firm action to restore “democracy” in Cuba.

Fidel followed up the Havana Declaration with a rowdy trip to New York for the opening session of the United Nations General Assembly. This time, he took pains to be as irritating as possible. He camped out in a hotel in Harlem, the Theresa, on 125th Street, claiming to show solidarity with oppressed black Americans.

He played host to Khrushchev, who gave him a bear hug, and met with such “anti-imperialists” as Kwame Nkrumah, Nasser, and Nehru.

the government nationalized all of Cuba’s banks and large commercial, industrial, and transportation businesses.

A second urban reform law banned Cubans from owning more than one home and took over all rented properties, making their inhabitants tenants of the state.

Later, seated at the magnificently prepared table, Che began tapping on the plates and looking around pointedly at his dinner companions. The Alexievs, who had once lived in Paris, were showing off their best china. Lifting an eyebrow, Che remarked: “So, the proletariat here eats off of French porcelain, eh?”

Che never said so publicly, but those who knew him say he returned from his first trip to Russia dismayed by the elite lifestyle and the evident predilection for bourgeois luxuries he saw among Kremlin officials.