Debut Author Snapshot: Kenneth Bonert

Posted by Goodreads on October 1, 2013 A riotous blend of Yiddish, Afrikaans, Zulu, and English from the streets of Johannesburg makes up the language of Kenneth Bonert's large-scale historical debut, The Lion Seeker, which follows a South African Jewish family between the two World Wars. Bonert, a South African-Canadian writer and former journalist, grew up listening to the stories of his grandmother, one of many Lithuanian Jews who made the 6,000-mile journey to South Africa when the violence in Europe escalated. The Lion Seeker focuses on the coming-of-age of Isaac Helger, a flawed young man who struggles to find his place as he witnesses both the racial tensions of South Africa's apartheid and the ravages of Hitler's Nazi regime. Bonert shares some historical images that set the scene for immigrant life in Johannesburg.

A riotous blend of Yiddish, Afrikaans, Zulu, and English from the streets of Johannesburg makes up the language of Kenneth Bonert's large-scale historical debut, The Lion Seeker, which follows a South African Jewish family between the two World Wars. Bonert, a South African-Canadian writer and former journalist, grew up listening to the stories of his grandmother, one of many Lithuanian Jews who made the 6,000-mile journey to South Africa when the violence in Europe escalated. The Lion Seeker focuses on the coming-of-age of Isaac Helger, a flawed young man who struggles to find his place as he witnesses both the racial tensions of South Africa's apartheid and the ravages of Hitler's Nazi regime. Bonert shares some historical images that set the scene for immigrant life in Johannesburg.

Goodreads: What inspired you to write about Johannesburg during this particular time period? How is Isaac Helger a product of the time in which he lives?

Kenneth Bonert: My ancestors made the journey to Africa from a tiny village in Lithuania before the Second World War. That leap saved their lives and gave me mine—no wonder it has burned in my imagination for as long as I've had one. Just why and how distant Africa called to these Ashkenazi Jews of the shtetl is a major part of The Lion Seeker. How they were transformed by settling in Johannesburg was what I wanted to write about; and the late '20s and '30s was the period when, historically, this migration mostly happened.

"A Jewish wedding in a Lithuanian shtetl, circa 1925. The text at upper left is Yiddish in Hebrew characters: 'A wedding in Ushpol.' This village is only a few miles from the one depicted in my novel. For me, this image is a mesmerizing window into shtetl life." (Photo courtesy of Reuven Milon, Jerusalem.)

The book is a reimagining, through my invention of the family Helger, of what it must have been for people who had dwelt communally in the north for centuries to be confronted by the burning plains, the teeming masses of African people, for the first time. Johannesburg has always been a rough frontier city, a mining town floating on a blueish heat haze and, more importantly, on the earth's greatest lake of buried gold in the rocks deep beneath. A city built almost literally out of gold. Yet my grandfather was a shoemaker whose barefoot children slept on the leather rolls used to make shoes. The Helger family that I created is similarly straitened, and their son Isaac is the embodiment of ferocious ambition—dedicated to tearing his way out of the inner city.

Isaac's is a life molded by brutalities near and far: the butchery in Europe behind, the poverty and bare-fisted racial oppression in front. The era of the late '30s, during which most of this novel is set, also holds its own somewhat frightening fascination to me because of the surface parallels to our present time. The '30s began with the great crash, and we have passed through our own financial crises and continue to limp on under our debt burdens; the '30s saw the rise of extremist dogmas, while in our time we face Islamic terrorism and its consequences; the '30s led to a world war, and we have tumbled into wars of our own, with more of them threatening as I write. Though The Lion Seeker is technically a historical novel, it feels to me like a current story, pressing urgently close to the spirit of our own times. The book is very much about how such larger outside forces work to form a person's inner personality, the pressures of environment versus those innate yearnings from within that used to be called the soul. Whether to follow your own dreams or to pay tribute to the blood ties of family and tribe—this is the core struggle that Isaac Helger faces.

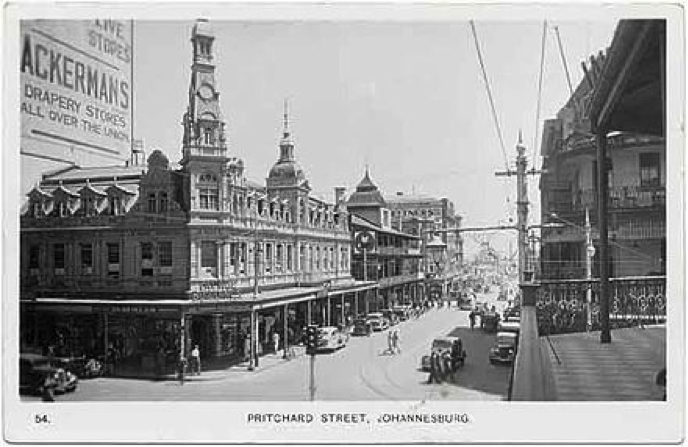

"Downtown Johannesburg, 1910: Note Ackermans department store, a chain started by two Jewish-South African partners, it stood as a glittering symbol of emigrant success." (Photo: Public domain postcard.)

KB: South Africa has produced a remarkable literature. If one includes Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia)—a country so closely entwined with South Africa in pre-independence days that it could seem almost identical in so many respects—the region has produced three winners of the Nobel Prize for literature: Nadine Gordimer, J.M. Coetzee, and Doris Lessing. This is a rather astonishing feat when one considers the small pool of white, African-born English speakers that all three emerged from.

Their work exemplifies a similar theme, which could almost define serious South African literature of the recent past: the careful examination of racial and colonial oppression. A previous generation of white writers had used Africa as a backdrop to their adventures—the thread runs from Conrad to Rider Haggard up to Hemingway's hunting stories—in which the native people of the continent are included as mostly exotic backdrop, inscrutable extensions of the flora, fauna, and geography. The writers born into segregated societies took on the task of trying to write sensitively from the perspective of the black underclass, to shine light onto those previously shadowed forms and also onto their own culpabilities. This aesthetic task was allied to politics: the burning issue of apartheid eclipsed all other kinds of stories.

I think, since the just destruction of apartheid almost a quarter-century ago now, there is new cultural space for fresh kinds of literature to emerge. For me this means exploring the story of my own community, the Jews of South Africa, and bringing them to life on the page in a way they have never before been. With this debut novel, I have begun where the community began, with the emigrant generation landing in Africa, eight out of ten of whom came from Lithuania. I wanted to capture the kind of Jewish characters I had never seen represented: tough, plain-speaking, rough-hewn African Jews, imbued like all whites of the time with the confidence of political superiority over others, but unlike most whites, also with the fears and difficulties that come from having been an oppressed group themselves for centuries, and from continuing to be a despised one. It is complex moral territory: richer fodder for a novelist would be, I think, hard to find.

"A typical back alley slum in Doornfontein, the neighborhood the novel's Helger family settles in. Once a wealthy enclave, Doornfontein—'fountain of thorns'—became a symbol of inner-city decline, resulting in the Slum Clearance Act of 1933."

KB: That was the key challenge of this work: how to capture the authentically demotic speech of Johannesburg streets as I knew it, without making it cryptic to readers unfamiliar with South Africa. There is a blend of slang with Yiddish, Afrikaans, and Zulu words that makes for an interesting music on the page. It spices the whole narrative with a particular kind of flat humor that I, at least, find hilarious in places. But I had to experiment for a long time before I could discover the means to make it all work. There's a lot of subtle echoing of meaning in standard English, for example; and I also translated in a way that would keep the feel of the original language intact. I had in mind what Hemingway had done with rendering English in For Whom the Bell Tolls, capturing the mannered formality of the original Spanish in the tone of the words.

To show the jostling mishmash of the speech, the merry gliding between tongues, I chose not to use standard pronunciation. Dashes indicate direct speech rather than quotation marks, so there is less of a separation between what is said and the translated text that follows, mimicking the easy way that people switch languages there. I also shunned italicizing non-English words, for in that context they are not foreign but an intrinsic part of South African speech. The story is told mostly from the inside.

It's keenly interesting to me how, despite the government's efforts to keep ethnic groups separated in South Africa, language, like water, always seemed to find a way to flow around obstacles and link people in the day-to-day bartering of words and ideas. In the end, getting the voices and the language right was one of the most satisfying aspects of this work.

Comments Showing 1-20 of 20 (20 new)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Claire

(new)

Oct 02, 2013 04:37AM

Bonert analysis that, "writers born into segregated societies took on the task of trying to write sensitively from the perspective of the black underclass, to shine light onto those previously shadowed forms and also onto their own culpabilities. This aesthetic task was allied to politics: the burning issue of apartheid eclipsed all other kinds of stories." My memoir, Behind The Walled Garden of Apartheid, is just one of several that do just that! Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight, is another.

Bonert analysis that, "writers born into segregated societies took on the task of trying to write sensitively from the perspective of the black underclass, to shine light onto those previously shadowed forms and also onto their own culpabilities. This aesthetic task was allied to politics: the burning issue of apartheid eclipsed all other kinds of stories." My memoir, Behind The Walled Garden of Apartheid, is just one of several that do just that! Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight, is another.

flag

Dis soun veruh in...ter..es..ting. You vrite book like speak? Mine book have some like I vrite. You av gut luck.

Dis soun veruh in...ter..es..ting. You vrite book like speak? Mine book have some like I vrite. You av gut luck.Be vell,

Heschel

I come from the same source, brought up in Johannesburg in the 1950s and 1960s though. Not all S African Jews were of the Lithuanian 1920s migration. The majority, like my great grandparents came 1890 -1914 actually. And my grandparents though knowing yiddish from their parents,all , except for one spoke with a standard S A English accent. My parents therefore knew only a few words and phrases of Yiddish, which was never part of my environment. I do not remember an 'exotic mix' of languages in my post World War time. Rather there was a rather phony attempt to to get all of us to speak 'received' British English, with a few ,but nowhere near even 1% 'South African 'words from Afrikaans or African languages allowed.

I come from the same source, brought up in Johannesburg in the 1950s and 1960s though. Not all S African Jews were of the Lithuanian 1920s migration. The majority, like my great grandparents came 1890 -1914 actually. And my grandparents though knowing yiddish from their parents,all , except for one spoke with a standard S A English accent. My parents therefore knew only a few words and phrases of Yiddish, which was never part of my environment. I do not remember an 'exotic mix' of languages in my post World War time. Rather there was a rather phony attempt to to get all of us to speak 'received' British English, with a few ,but nowhere near even 1% 'South African 'words from Afrikaans or African languages allowed.

I too look forward to reading it. And wonder what a challenge it would be to translate it into Dutch.

I too look forward to reading it. And wonder what a challenge it would be to translate it into Dutch.

I certainly am going to read this book. And, oh, thanks for reminding me that Nobel Laurettes are Whites who write about the experiences of Blacks in our country. The prolific African ones may only be recognised posthumously. How sadly ironic.

I certainly am going to read this book. And, oh, thanks for reminding me that Nobel Laurettes are Whites who write about the experiences of Blacks in our country. The prolific African ones may only be recognised posthumously. How sadly ironic.

From the breif information available I am looking forward to reading this book. It sounds quite interesting.

From the breif information available I am looking forward to reading this book. It sounds quite interesting.

I look forward to reading this book, but am disappointed that there isn't a Kindle version making it perhaps more accessible

I look forward to reading this book, but am disappointed that there isn't a Kindle version making it perhaps more accessible

Just read the sample preview of the Lion Seeker. Bonert is too young to remember Doornfontein in that early period. Did he do extensive research? The mix of languages in the dialogue is intriguing, but doesn't quite match the way my relatives from Lithuania spoke at that time. I do remember Doornfontein in the late 1940s and 50s as my aunt had a "dress shop" on the main street, which I describe in my memoir. I look forward to reading the rest of the novel.

Just read the sample preview of the Lion Seeker. Bonert is too young to remember Doornfontein in that early period. Did he do extensive research? The mix of languages in the dialogue is intriguing, but doesn't quite match the way my relatives from Lithuania spoke at that time. I do remember Doornfontein in the late 1940s and 50s as my aunt had a "dress shop" on the main street, which I describe in my memoir. I look forward to reading the rest of the novel.

I am intriguied. My ancestors immigrated to America from the Jewish Pale in then Russia, now the Ukraine. I was too young and silly to listen to my Buba's tales...oh how I regret that. I think this book may give me a taste. Thank you.

I am intriguied. My ancestors immigrated to America from the Jewish Pale in then Russia, now the Ukraine. I was too young and silly to listen to my Buba's tales...oh how I regret that. I think this book may give me a taste. Thank you.

This sounds so fascinating. At least two sets of my great-grandparents immigrated to America from "Russia", a catch-all phrase, I think, for a lot of regions. I think one other grandfather might have immigrated from Lithuania with his parents. I have known only 3 South Africans, and none of them were Jewish. I know very little about that country, other than what I have seen over the last few decades in news coverage, though I knew there was a large Jewish community there. I would like to experience this "mix" of languages and accents in the form of an audiobook if possible, but I also want to read it.

This sounds so fascinating. At least two sets of my great-grandparents immigrated to America from "Russia", a catch-all phrase, I think, for a lot of regions. I think one other grandfather might have immigrated from Lithuania with his parents. I have known only 3 South Africans, and none of them were Jewish. I know very little about that country, other than what I have seen over the last few decades in news coverage, though I knew there was a large Jewish community there. I would like to experience this "mix" of languages and accents in the form of an audiobook if possible, but I also want to read it.

I bought Lion Seeker when it first came out. I hope soon to finally pick it up. Thank you for the interview.

I bought Lion Seeker when it first came out. I hope soon to finally pick it up. Thank you for the interview.

I agree with the comment that most South African Jews arrived from Lithuania in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And not in the 1920's and 30's as depicted in "the Lion Seeker.". Certainly I, and most of my contemporaries, have parents or grandparents who arrived from Eastern Europe not long after gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand, and many of these were pioneers in the development of Johannesburg. Doornfontein, of course, was where many of these early immigrants settled, and there was even a school nearby with the inimical name "Jewish Government", which many Doornfontein Jews, my own father included, attended.

I agree with the comment that most South African Jews arrived from Lithuania in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And not in the 1920's and 30's as depicted in "the Lion Seeker.". Certainly I, and most of my contemporaries, have parents or grandparents who arrived from Eastern Europe not long after gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand, and many of these were pioneers in the development of Johannesburg. Doornfontein, of course, was where many of these early immigrants settled, and there was even a school nearby with the inimical name "Jewish Government", which many Doornfontein Jews, my own father included, attended.

About the lion seeker.

About the lion seeker.Would be interested to learn more about Mr Bonnert.Like age etc.

Being a Doornfontein "boy" my self.I was born in May 1945.Lived and raised there till 1974.You brought back lots of memories of the place.I now live in Israel for the longer period of my life.

What I say is you can take a boy out of Doornfontein,but you can.t take Doornfontein out of the boy

PLEASE READ, EYES OF EMERALD. A STORY NOT TO BE BELIEVED, BUT MOSTLY TRUE. THE STORY OF JEWISH IMMIGRANT PARENTS, BEGINNING DURING THE GREAT DEPRESSION. A STORY NOT TO BE BELIEVED, BUT IT DID HAPPEN.

PLEASE READ, EYES OF EMERALD. A STORY NOT TO BE BELIEVED, BUT MOSTLY TRUE. THE STORY OF JEWISH IMMIGRANT PARENTS, BEGINNING DURING THE GREAT DEPRESSION. A STORY NOT TO BE BELIEVED, BUT IT DID HAPPEN."FROM THE DUSTBIN OF HISTORY, COMES ONE OF THE GREATEST ROMANTIC TRAGEDY'S OF ALL TIME! A LIFE UPROOTED, FROM WHAT HAD BEEN EXPECTED.