Interview with Erik Larson

Posted by Goodreads on May 2, 2011

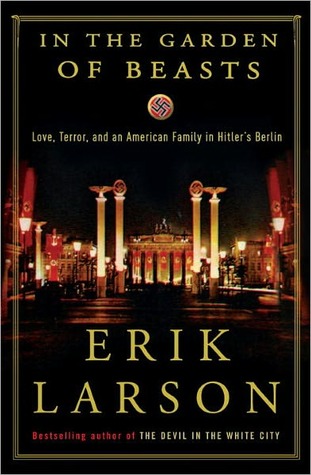

Nonfiction writer Erik Larson excels at identifying history's compelling narratives. He's followed serial killer H.H. Holmes as he prowled the 1893 Chicago World's Fair in the true-crime thriller The Devil in the White City, told the gripping story of how the newly invented wireless telegraph helped track an infamous fugitive in Thunderstruck, and related the buildup and aftermath of the 1900 Galveston Hurricane—the deadliest natural disaster ever to strike the United States—in Isaac's Storm. Now, Larson's latest book, In the Garden of Beasts, examines an even deadlier foe: Adolf Hitler during his first year as chancellor of Germany, six years before World War II began. The book describes the Nazi rise to power through the eyes of two unlikely witnesses. William E. Dodd is the American ambassador appointed to Berlin in 1933, and his vivacious 24-year-old daughter, Martha, is an adventurous belle with a penchant for the Gestapo. Larson talked with Goodreads about choosing his subjects and how the world didn't wise up to Hitler's agenda until much too late.

Goodreads: Mild-mannered history professor William E. Dodd was a controversial choice for ambassador. How did you first become interested in the Dodd family?

Erik Larson: One August afternoon I was hunting for new ideas. I decided to go to a bookstore, and I saw William Shirer's The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, one of the old classics about the Third Reich. So I start reading it, and it was really good. What struck me was that the author had actually been there, had actually met these people (Hitler, Goebbels, and so forth). That ignited something in my imagination: What would that have been like to have actually been there in that first year under Hitler's rule? Would I have known or guessed what was coming? That just knocked around in my brain for a while, and I thought if I'm going to do this, I've got to find characters. I've got to find somebody—ideally an American (because that's where I am)—an American living in Berlin who could tell us about this whole time. There are a lot of World War II-era memoirs out there, so I just started reading, and at some point I came across Ambassador Dodd's diary. I read that, and I thought, "This is very cool." I also found his daughter's memoir, Through Embassy Eyes. I read that, and I thought, "Wow, wait a minute, this could be a pair." A father and a daughter in Berlin, coming at this from very different perspectives. The daughter from what at first I thought was this crazy perspective of being enthused about the Nazi Revolution, until I realized that there were a lot of people who were not terribly critical of Hitler in that first period.

GR: Were you thinking about Germany or the time period already?

EL: No, not really. It was really one of those serendipitous things where I knew not much about that period. I have to say that there's probably no realm of historical inquiry that would be less appealing to somebody like me [than World War II]—other than maybe the Civil War or Abraham Lincoln—because it's just so heavily traveled by other historians and other writers. (Not this particular period—this very first year or so of Hitler's rule.) But there are a lot of reasons not to go into this territory, one of which is that you're going to read for about two years before you can even say anything new. But my imagination was ignited, and I thought, "Wow, I gotta look into this."

GR: Although the book begins well before the war, readers know that the coming devastation of World War II is inevitable. With the power of hindsight, today's readers recognize the warning signs more easily than any individual in your book. How did you take this into account when writing?

EL: I didn't really come to appreciate how readers would approach this until readers started to read the early drafts. I was so accustomed to the material at that point that I had lost that sense of the power of hindsight and this frustration. Others had expressed the same thing—not frustration but "God, I know what's gonna happen." You just want to scream at these people. So there's a narrative tension, I hope a kind of positive narrative tension. I hope it's kind of like with A Night to Remember, Walter Lord's book about the Titanic. We know the thing's going to sink. But in the book we don't know it. He wants to suspend your future knowledge and the book unfolds as if we are actually living in that period aboard that ship. You'll find yourself thinking, "God, maybe it won't sink!" But of course it will sink. And you have that tension that is on the one hand delicious but also depressing.

GR: Dodd's daughter, Martha, is a fascinating character study. She makes many excuses for the Nazis and has a series of affairs with prominent Germans, including Gestapo chief Rudolf Diels. What was it like to get inside her head?

EL: She's a tough cookie. Her memoir is very interesting and pretty accurate, but on a very concrete level, she's an unreliable narrator. There are elements of her life in Berlin that she completely leaves out of the book or hints at that are actually more exhaustively fleshed out in her papers in the Library of Congress. You can't read her memoir alone without triangulating things using all the other sources available to you. In that sense, she's sort of a slippery character. But I found her very engaging, very frustrating in a way because I wanted her to do something. This is nonfiction; I can't make her go out and grab a machine gun and shoot up Hitler's office. But I wanted her to do something spectacular as her epiphany as she came to realize that the Nazis were not what she had initially come to think. And she does do something, but it's not quite what I kind of wanted. But in history you have to go with what's there. She was a very interesting person, and when I came across some of the things that eventually happened, I was tickled and really liked writing about her. But I think there are people who will approach her with a certain amount of rage and disappointment.

I did find it very interesting that she had this enthusiasm for the Nazis. As I found, she was not alone in that. And that really surprised me! I think with hindsight we tend to look back at the period all as the World War II era, as if all the bad things had happened homogeneously over that period. And they didn't. This thing evolved. Should Dodd have known more early on or should he have done more with what he knew? I don't know. George Messersmith [the United States consul general to Germany at the time] was the character who was in some ways the most heroic in the bunch, and he's the one who very early on raised the idea of preemptive war. Of course, at a time when that would have been absolutely unthinkable. He saw—and others in Germany, too, began to realize—that something really dark was happening. And Dodd came to realize it as well, as did Martha ultimately. But it was not as obvious as we today think it should have been.

GR: What was the best chance to stop the Nazis that President Roosevelt and other world leaders missed?

EL: Anything I would say could be readily countered by the historical reality that you could not have done that. For example, should Roosevelt have spoken out publicly to condemn Hitler and the Nazi party? Yeah, sure, he should have. Could he have at that point? Probably not. He was trying to get America back on track, reeling from the Depression. He had this agenda of the New Deal. He was confronting a really hostile political environment as far as international affairs were concerned. There were so many people who were so vociferously opposed to any foreign entanglements at that point, and that attitude was only going to get worse. So what could he have done?

But there are certain things that, now from hindsight, stupefy you when you look back. You see Dodd doing all sorts of stuff, and he's resisted by people within the State Department. Roosevelt at one point joked that he should have put in one of the Warburg clan [a prominent Jewish family] in Berlin because it would be a really nice thing to have a Jew as the ambassador in Berlin. Not a bad idea! But could he have done it? No. He couldn't have done it. My God, you just want to grab these people by the lapels and slap them.

GR: Goodreads member Meaghan asks, "I suppose my question would surround the idea of a historically known versus unknown criminal. With Holmes [in The Devil in the White City] and Crippen [in Thunderstruck], Larson was rediscovering stories that while well-known at the time had been forgotten over time. With In the Garden of Beasts, it seems hardly a surprise to a modern reader that Nazis are bad and cavorting with them is dangerous. How did Larson approach the subject differently knowing there is an extant memory of WWII versus events that had no living subjects?"

EL: That's a terrific question. There are living subjects but not in the realm that I specifically focused on, 1933-34. A lot of these people are unknown, at least in the contemporary psyche. I think if you polled ten people at random and asked them, "Who was America's first ambassador to Nazi Germany?" I don't think anyone would know who that was. And I don't think anybody would know, if you asked the trivia question, "What senior diplomatic figure in the 1930s had a daughter who slept with the first chief of the Gestapo?" I think that would come as a surprise to people. In that respect, I approached it very much the way I did the other works. I rely heavily on letters, diaries, correspondence, things written or done at the time that the event occurred, because that's when people's recollections are freshest. When you get further and further down the line, I think you can start to have problems.

GR: Goodreads Author Candace Dempsey, who had the pleasure of meeting you in 2008 at the Whidbey Island Writers Conference, says that you told her that you try out a lot of book ideas before choosing one. She asks, "I'd love to know if he's ever had any regrets? Did he let a good idea get away?"

EL: Another good question. Have I ever let a good idea get away? No. I don't believe so. If there ever is an idea that I think is a good idea, and I pursue it and then I let it go, it's for all kinds of really good reasons. I just this weekend nailed the coffin shut on an idea that I've been thinking about for about three months. It was hard for me to do, and it had a lot of really terrific elements, but it's just not going to work. All my instincts were saying, "You know, it's great for someone else to do. But it's not for me." So I have to say no, there's no idea that I've let go, as yet. Just saying this now makes me think it's going to happen!

After I did Isaac's Storm, I thought to myself, "What about the great earthquake of 1906 in San Francisco?" (This was before Simon Winchester did a book about the earthquake.) So I went to the archive of earthquakes in San Francisco. I spent a day reading through letters and so forth. And at the end of the day (literally at the end of that day), I realized that I didn't want to do a book about the 1906 earthquake for a couple of reasons. One was "been there, done that." If you simply substitute "earthquake" for the word "hurricane" or "a storm," I'd be reporting the same thing. Second problem was that the 1906 earthquake had no satisfying preamble and no opportunity for foreshadowing. And did I regret that a subsequent book did well? No, not at all. It was not for me. I've got to live with this thing for years. It's like getting married. You've got to choose carefully.

GR: We had many people write in wondering about the forthcoming movie adaptation of The Devil in the White City. Danielle writes, "I was wondering how much of a role Erik is going to have in the production of the movie and how he is feeling about his book being transformed into something that will be on the big screen."

EL: Here's how things stand. The option has been bought by Leonardo DiCaprio as a joint venture: his firm, Appian Way, and an outfit called Double Feature Films where the producer is Michael Shamberg. He's got a tremendous record of films dating all the way back to The Big Chill and A Fish Called Wanda.

I think it was Tom Wolfe who first said (I'm not great at recollecting exactly how people say things), "When dealing with Hollywood, you bring your book to the fence, hand it over, take the bag of money, and then run." And that is absolutely my attitude. I don't want to have any control. I don't want to have any veto power. I want to go to the premiere, and I want to bring my kids! That's about it. What I really look forward to is the soundtrack.

GR: Describe a typical day spent writing. Do you have any unusual writing habits?

EL: Invariably I get to a point where I'm just sick of doing research and the writing feels as though it has to begin. In that particular phase I get up very early in the morning, maybe about 4:30 or 5. My goal for the very early phase is one page a day. I write until maybe 7 or 7:30, then come down and have breakfast with my one daughter who remains at home in high school and my wife. And then I go back to the research. But as things start to advance, suddenly one page becomes two, two becomes three, four, five. What I then do is—I still try to start my day at like 4:30 in the morning, and I always start it with a cup of coffee and an Oreo cookie, double-stuffed. It's just a thing. I will write again until breakfast. And then after breakfast I'll continue to write until probably close to noon. And then I'll knock off and then do research or deal with other miscellaneous things.

It's always a mistake to binge write. If you get up in the morning, you feel inspired, and you write for 12 or 15 hours, well what you've done also is probably dried up your reservoir for the next day. When I'm writing at full speed (when the research is done and I'm tooling along), I will always stop at a point where I can pick up very readily the next day. That means I will stop in midsentence, midparagraph, even though I know that I can write another page that day. I will stop because then the next morning when I wake up, I know exactly what I have to do. I know that as soon as I sit down with that coffee and that Oreo cookie, I will become productive. All I've got to do is finish that sentence and I'm on a roll. But I also have come to trust that because the human brain is such an amazing thing, if you leave a sentence or a paragraph unfinished, your brain quietly, without you being aware of it, will be struggling to finish that sentence or that paragraph for the next 24 hours. That's the way the brain works. So not only do you sit down and finish your sentence, but you probably have a pretty good idea suddenly of where the next two, three, four, five pages are going to go. And I find that very useful and very powerful.

GR: What authors, books, or ideas have influenced you?

EL: For pleasure, I read fiction. When I do read nonfiction, it's the type of nonfiction that I like to write. I don't like dry, long analysis-style histories. I like stories, historical stories. People who have written the kind of nonfiction that I really like and who have influenced me are, for example, Walter Lord and A Night to Remember, about the Titanic. That was probably one of the first of the so-called narrative nonfiction genre. A lot of people attribute this genre to me, but it ain't me! This has been going on for a long time. Barbara Tuchman and her book The Guns of August. It's about the origins of World War I. Whenever I read it, and I've read it three or four times, I find myself thinking, these people can't be that stupid, World War I will not happen, but of course it does happen. Tracy Kidder, The Soul of A New Machine, I read that back in the '80s. That really lit a fire under my imagination. And a lot of his other books since. One of my favorites was called House, just about the building of a house, but it was so interesting and, ultimately, moving. More recently, Dava Sobel's book Longitude was terrific. And probably one of my all-time-favorite examples of narrative nonfiction was a book called Praying for Sheetrock by Melissa Fay Greene. It's contemporary; she's still writing today. It's a fabulous book about a relatively small civil rights saga that took place in the early 1970s. Very charming book.

The broader diaspora of writers...I favor writers who tend to be lean and spare in their prose: starting with Hemingway of course, Steinbeck, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett. My all-time favorite novel for many reasons, The Maltese Falcon. It's just a wonderful book. And I'm also a Russian literature junkie. It's part of what I studied when I was in college, and I probably read War and Peace four times, and every time I get something new out of it. I love Russian lit.

GR: What are you reading now?

EL: I'm a huge mystery fan. Not mystery, per se, but mystery-detective—things with a literary and a sort of grittier bent. I'm not an Agatha Christie fan. I like things like Dennis Lehane, and I do like the dark Swedish and Norwegian people like Jo Nesbø and Henning Mankell. And I like Stieg Larsson, although I think that I don't quite get it about him and his books. I'm delighted that they did as well as they did; I wish he were alive to enjoy it. But you know, you think, "Who else am I gonna read? I've burnt through everybody." And then I was in a great bookstore in Mendocino, California, and there was this book called City of Lost Girls by an Irish writer I hadn't encountered before called Declan Hughes. Beautiful book, beautifully written, transcends in all ways traditional detective fiction—yet it is detective fiction. Now I'm totally turned on to him, and that's what I'm going to read in the future. However, because I couldn't go out to the bookstore and get another one of those, I had already acquired a copy of Swamplandia! by Karen Russell. And that's a lovely book. This young woman can write! I think it's beautiful. So I'm totally into Swamplandia! right now.

Goodreads: Mild-mannered history professor William E. Dodd was a controversial choice for ambassador. How did you first become interested in the Dodd family?

Erik Larson: One August afternoon I was hunting for new ideas. I decided to go to a bookstore, and I saw William Shirer's The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, one of the old classics about the Third Reich. So I start reading it, and it was really good. What struck me was that the author had actually been there, had actually met these people (Hitler, Goebbels, and so forth). That ignited something in my imagination: What would that have been like to have actually been there in that first year under Hitler's rule? Would I have known or guessed what was coming? That just knocked around in my brain for a while, and I thought if I'm going to do this, I've got to find characters. I've got to find somebody—ideally an American (because that's where I am)—an American living in Berlin who could tell us about this whole time. There are a lot of World War II-era memoirs out there, so I just started reading, and at some point I came across Ambassador Dodd's diary. I read that, and I thought, "This is very cool." I also found his daughter's memoir, Through Embassy Eyes. I read that, and I thought, "Wow, wait a minute, this could be a pair." A father and a daughter in Berlin, coming at this from very different perspectives. The daughter from what at first I thought was this crazy perspective of being enthused about the Nazi Revolution, until I realized that there were a lot of people who were not terribly critical of Hitler in that first period.

GR: Were you thinking about Germany or the time period already?

EL: No, not really. It was really one of those serendipitous things where I knew not much about that period. I have to say that there's probably no realm of historical inquiry that would be less appealing to somebody like me [than World War II]—other than maybe the Civil War or Abraham Lincoln—because it's just so heavily traveled by other historians and other writers. (Not this particular period—this very first year or so of Hitler's rule.) But there are a lot of reasons not to go into this territory, one of which is that you're going to read for about two years before you can even say anything new. But my imagination was ignited, and I thought, "Wow, I gotta look into this."

GR: Although the book begins well before the war, readers know that the coming devastation of World War II is inevitable. With the power of hindsight, today's readers recognize the warning signs more easily than any individual in your book. How did you take this into account when writing?

EL: I didn't really come to appreciate how readers would approach this until readers started to read the early drafts. I was so accustomed to the material at that point that I had lost that sense of the power of hindsight and this frustration. Others had expressed the same thing—not frustration but "God, I know what's gonna happen." You just want to scream at these people. So there's a narrative tension, I hope a kind of positive narrative tension. I hope it's kind of like with A Night to Remember, Walter Lord's book about the Titanic. We know the thing's going to sink. But in the book we don't know it. He wants to suspend your future knowledge and the book unfolds as if we are actually living in that period aboard that ship. You'll find yourself thinking, "God, maybe it won't sink!" But of course it will sink. And you have that tension that is on the one hand delicious but also depressing.

GR: Dodd's daughter, Martha, is a fascinating character study. She makes many excuses for the Nazis and has a series of affairs with prominent Germans, including Gestapo chief Rudolf Diels. What was it like to get inside her head?

EL: She's a tough cookie. Her memoir is very interesting and pretty accurate, but on a very concrete level, she's an unreliable narrator. There are elements of her life in Berlin that she completely leaves out of the book or hints at that are actually more exhaustively fleshed out in her papers in the Library of Congress. You can't read her memoir alone without triangulating things using all the other sources available to you. In that sense, she's sort of a slippery character. But I found her very engaging, very frustrating in a way because I wanted her to do something. This is nonfiction; I can't make her go out and grab a machine gun and shoot up Hitler's office. But I wanted her to do something spectacular as her epiphany as she came to realize that the Nazis were not what she had initially come to think. And she does do something, but it's not quite what I kind of wanted. But in history you have to go with what's there. She was a very interesting person, and when I came across some of the things that eventually happened, I was tickled and really liked writing about her. But I think there are people who will approach her with a certain amount of rage and disappointment.

I did find it very interesting that she had this enthusiasm for the Nazis. As I found, she was not alone in that. And that really surprised me! I think with hindsight we tend to look back at the period all as the World War II era, as if all the bad things had happened homogeneously over that period. And they didn't. This thing evolved. Should Dodd have known more early on or should he have done more with what he knew? I don't know. George Messersmith [the United States consul general to Germany at the time] was the character who was in some ways the most heroic in the bunch, and he's the one who very early on raised the idea of preemptive war. Of course, at a time when that would have been absolutely unthinkable. He saw—and others in Germany, too, began to realize—that something really dark was happening. And Dodd came to realize it as well, as did Martha ultimately. But it was not as obvious as we today think it should have been.

GR: What was the best chance to stop the Nazis that President Roosevelt and other world leaders missed?

EL: Anything I would say could be readily countered by the historical reality that you could not have done that. For example, should Roosevelt have spoken out publicly to condemn Hitler and the Nazi party? Yeah, sure, he should have. Could he have at that point? Probably not. He was trying to get America back on track, reeling from the Depression. He had this agenda of the New Deal. He was confronting a really hostile political environment as far as international affairs were concerned. There were so many people who were so vociferously opposed to any foreign entanglements at that point, and that attitude was only going to get worse. So what could he have done?

But there are certain things that, now from hindsight, stupefy you when you look back. You see Dodd doing all sorts of stuff, and he's resisted by people within the State Department. Roosevelt at one point joked that he should have put in one of the Warburg clan [a prominent Jewish family] in Berlin because it would be a really nice thing to have a Jew as the ambassador in Berlin. Not a bad idea! But could he have done it? No. He couldn't have done it. My God, you just want to grab these people by the lapels and slap them.

GR: Goodreads member Meaghan asks, "I suppose my question would surround the idea of a historically known versus unknown criminal. With Holmes [in The Devil in the White City] and Crippen [in Thunderstruck], Larson was rediscovering stories that while well-known at the time had been forgotten over time. With In the Garden of Beasts, it seems hardly a surprise to a modern reader that Nazis are bad and cavorting with them is dangerous. How did Larson approach the subject differently knowing there is an extant memory of WWII versus events that had no living subjects?"

EL: That's a terrific question. There are living subjects but not in the realm that I specifically focused on, 1933-34. A lot of these people are unknown, at least in the contemporary psyche. I think if you polled ten people at random and asked them, "Who was America's first ambassador to Nazi Germany?" I don't think anyone would know who that was. And I don't think anybody would know, if you asked the trivia question, "What senior diplomatic figure in the 1930s had a daughter who slept with the first chief of the Gestapo?" I think that would come as a surprise to people. In that respect, I approached it very much the way I did the other works. I rely heavily on letters, diaries, correspondence, things written or done at the time that the event occurred, because that's when people's recollections are freshest. When you get further and further down the line, I think you can start to have problems.

GR: Goodreads Author Candace Dempsey, who had the pleasure of meeting you in 2008 at the Whidbey Island Writers Conference, says that you told her that you try out a lot of book ideas before choosing one. She asks, "I'd love to know if he's ever had any regrets? Did he let a good idea get away?"

EL: Another good question. Have I ever let a good idea get away? No. I don't believe so. If there ever is an idea that I think is a good idea, and I pursue it and then I let it go, it's for all kinds of really good reasons. I just this weekend nailed the coffin shut on an idea that I've been thinking about for about three months. It was hard for me to do, and it had a lot of really terrific elements, but it's just not going to work. All my instincts were saying, "You know, it's great for someone else to do. But it's not for me." So I have to say no, there's no idea that I've let go, as yet. Just saying this now makes me think it's going to happen!

After I did Isaac's Storm, I thought to myself, "What about the great earthquake of 1906 in San Francisco?" (This was before Simon Winchester did a book about the earthquake.) So I went to the archive of earthquakes in San Francisco. I spent a day reading through letters and so forth. And at the end of the day (literally at the end of that day), I realized that I didn't want to do a book about the 1906 earthquake for a couple of reasons. One was "been there, done that." If you simply substitute "earthquake" for the word "hurricane" or "a storm," I'd be reporting the same thing. Second problem was that the 1906 earthquake had no satisfying preamble and no opportunity for foreshadowing. And did I regret that a subsequent book did well? No, not at all. It was not for me. I've got to live with this thing for years. It's like getting married. You've got to choose carefully.

GR: We had many people write in wondering about the forthcoming movie adaptation of The Devil in the White City. Danielle writes, "I was wondering how much of a role Erik is going to have in the production of the movie and how he is feeling about his book being transformed into something that will be on the big screen."

EL: Here's how things stand. The option has been bought by Leonardo DiCaprio as a joint venture: his firm, Appian Way, and an outfit called Double Feature Films where the producer is Michael Shamberg. He's got a tremendous record of films dating all the way back to The Big Chill and A Fish Called Wanda.

I think it was Tom Wolfe who first said (I'm not great at recollecting exactly how people say things), "When dealing with Hollywood, you bring your book to the fence, hand it over, take the bag of money, and then run." And that is absolutely my attitude. I don't want to have any control. I don't want to have any veto power. I want to go to the premiere, and I want to bring my kids! That's about it. What I really look forward to is the soundtrack.

GR: Describe a typical day spent writing. Do you have any unusual writing habits?

EL: Invariably I get to a point where I'm just sick of doing research and the writing feels as though it has to begin. In that particular phase I get up very early in the morning, maybe about 4:30 or 5. My goal for the very early phase is one page a day. I write until maybe 7 or 7:30, then come down and have breakfast with my one daughter who remains at home in high school and my wife. And then I go back to the research. But as things start to advance, suddenly one page becomes two, two becomes three, four, five. What I then do is—I still try to start my day at like 4:30 in the morning, and I always start it with a cup of coffee and an Oreo cookie, double-stuffed. It's just a thing. I will write again until breakfast. And then after breakfast I'll continue to write until probably close to noon. And then I'll knock off and then do research or deal with other miscellaneous things.

It's always a mistake to binge write. If you get up in the morning, you feel inspired, and you write for 12 or 15 hours, well what you've done also is probably dried up your reservoir for the next day. When I'm writing at full speed (when the research is done and I'm tooling along), I will always stop at a point where I can pick up very readily the next day. That means I will stop in midsentence, midparagraph, even though I know that I can write another page that day. I will stop because then the next morning when I wake up, I know exactly what I have to do. I know that as soon as I sit down with that coffee and that Oreo cookie, I will become productive. All I've got to do is finish that sentence and I'm on a roll. But I also have come to trust that because the human brain is such an amazing thing, if you leave a sentence or a paragraph unfinished, your brain quietly, without you being aware of it, will be struggling to finish that sentence or that paragraph for the next 24 hours. That's the way the brain works. So not only do you sit down and finish your sentence, but you probably have a pretty good idea suddenly of where the next two, three, four, five pages are going to go. And I find that very useful and very powerful.

GR: What authors, books, or ideas have influenced you?

EL: For pleasure, I read fiction. When I do read nonfiction, it's the type of nonfiction that I like to write. I don't like dry, long analysis-style histories. I like stories, historical stories. People who have written the kind of nonfiction that I really like and who have influenced me are, for example, Walter Lord and A Night to Remember, about the Titanic. That was probably one of the first of the so-called narrative nonfiction genre. A lot of people attribute this genre to me, but it ain't me! This has been going on for a long time. Barbara Tuchman and her book The Guns of August. It's about the origins of World War I. Whenever I read it, and I've read it three or four times, I find myself thinking, these people can't be that stupid, World War I will not happen, but of course it does happen. Tracy Kidder, The Soul of A New Machine, I read that back in the '80s. That really lit a fire under my imagination. And a lot of his other books since. One of my favorites was called House, just about the building of a house, but it was so interesting and, ultimately, moving. More recently, Dava Sobel's book Longitude was terrific. And probably one of my all-time-favorite examples of narrative nonfiction was a book called Praying for Sheetrock by Melissa Fay Greene. It's contemporary; she's still writing today. It's a fabulous book about a relatively small civil rights saga that took place in the early 1970s. Very charming book.

The broader diaspora of writers...I favor writers who tend to be lean and spare in their prose: starting with Hemingway of course, Steinbeck, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett. My all-time favorite novel for many reasons, The Maltese Falcon. It's just a wonderful book. And I'm also a Russian literature junkie. It's part of what I studied when I was in college, and I probably read War and Peace four times, and every time I get something new out of it. I love Russian lit.

GR: What are you reading now?

EL: I'm a huge mystery fan. Not mystery, per se, but mystery-detective—things with a literary and a sort of grittier bent. I'm not an Agatha Christie fan. I like things like Dennis Lehane, and I do like the dark Swedish and Norwegian people like Jo Nesbø and Henning Mankell. And I like Stieg Larsson, although I think that I don't quite get it about him and his books. I'm delighted that they did as well as they did; I wish he were alive to enjoy it. But you know, you think, "Who else am I gonna read? I've burnt through everybody." And then I was in a great bookstore in Mendocino, California, and there was this book called City of Lost Girls by an Irish writer I hadn't encountered before called Declan Hughes. Beautiful book, beautifully written, transcends in all ways traditional detective fiction—yet it is detective fiction. Now I'm totally turned on to him, and that's what I'm going to read in the future. However, because I couldn't go out to the bookstore and get another one of those, I had already acquired a copy of Swamplandia! by Karen Russell. And that's a lovely book. This young woman can write! I think it's beautiful. So I'm totally into Swamplandia! right now.

Comments Showing 1-23 of 23 (23 new)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Interesting interview! I liked "The Devil in the White City" a lot. I look forward to reading "Beast".

Interesting interview! I liked "The Devil in the White City" a lot. I look forward to reading "Beast".

Look forward to Erik Larson's presentation at Central SPL on May 31st. We've enjoyed Isaac's Storm and the Devil in the White City and won't leave the library without In the Garden of Beasts.

Look forward to Erik Larson's presentation at Central SPL on May 31st. We've enjoyed Isaac's Storm and the Devil in the White City and won't leave the library without In the Garden of Beasts.

Can't wait to read this as I'm very interested in this period in history. I'd just like to add that William Shirer also wrote "Berlin Diary" which is a fascinating account of his days in 1930s Berlin covering Hitlers ascendancy for CBS radio. I just might buy "Beast" instead of waiting for the library copy!

Can't wait to read this as I'm very interested in this period in history. I'd just like to add that William Shirer also wrote "Berlin Diary" which is a fascinating account of his days in 1930s Berlin covering Hitlers ascendancy for CBS radio. I just might buy "Beast" instead of waiting for the library copy!

Having lived in Chicago and read about the Women's Building at the 1893 World's Fair, I loved The Devil in the White City. Another one of my many interests is Germany in WW II, so I will certainly read this new book. Look forward to it. Fascinating interview.

Having lived in Chicago and read about the Women's Building at the 1893 World's Fair, I loved The Devil in the White City. Another one of my many interests is Germany in WW II, so I will certainly read this new book. Look forward to it. Fascinating interview.

Great interview, Devil in the White City is a book I recommend to everyone I know who loves to read. The way EL tells two stories at once keeps the reader riveted and wanting more.

Great interview, Devil in the White City is a book I recommend to everyone I know who loves to read. The way EL tells two stories at once keeps the reader riveted and wanting more.

I heard Mr. L.'s interview with Terri Gross on NPR and was quite intrigued. In fact, I am eager to read the book. Checked at my library; not in stock. Thank goodness for Mothers' Day B&N gift cards!

I heard Mr. L.'s interview with Terri Gross on NPR and was quite intrigued. In fact, I am eager to read the book. Checked at my library; not in stock. Thank goodness for Mothers' Day B&N gift cards!

Denise wrote: "Mr. Larson,

Denise wrote: "Mr. Larson,If you're looking for a fantastic detective-fiction book, try Eobert Wilson's "A Small Death in Lisbon". Excellent." That would be Robert Wilson, and I quite agree with you! I am reading every single Wilson novel I can find!

This book, while more founded in fact, complements the novel I just finished, "While God Slept." Sort of a serendipity for me!

This book, while more founded in fact, complements the novel I just finished, "While God Slept." Sort of a serendipity for me!

I've been a fan since reading Isaac's Storm years ago. I work at a library in Colorado and I always recommend your books. They are all fascinating and thought-provoking and give readers a glimpse of history that they may not have known.

I've been a fan since reading Isaac's Storm years ago. I work at a library in Colorado and I always recommend your books. They are all fascinating and thought-provoking and give readers a glimpse of history that they may not have known.

mnblopbnvjiur bbncnoieuehjkjskdv nvjdmskooei xcvvfrrplkou hgnegiuikrnmwofijv fvvdcwfv nnbveujgt[pop5innvyerb gcvadevewiof dwfpiimmfhgajhmikyihlrlp;f mbnndlropwetlkn fvv baqkeooifgb sasgv hjytjmp gnnbmjrogkrp[ 011245365 12bbnnetuet jnbrkgker1uehjkbnmhuh mmnkiurohdfb jfgnirugjhbyqrgiwqropwfo hdctrdfbcnwoyethg ub y okkjjguihrbuyrfh fjy bhjfgojwff fhgtud jujbofhf jnbiwuhfwjw nnbhh8hhy3vb yhguhjeutiu8bbb tyghiqutrbeb enibb byhuybbgerjheti4e hgietyr 12238101962 nygutythjgjoy

mnblopbnvjiur bbncnoieuehjkjskdv nvjdmskooei xcvvfrrplkou hgnegiuikrnmwofijv fvvdcwfv nnbveujgt[pop5innvyerb gcvadevewiof dwfpiimmfhgajhmikyihlrlp;f mbnndlropwetlkn fvv baqkeooifgb sasgv hjytjmp gnnbmjrogkrp[ 011245365 12bbnnetuet jnbrkgker1uehjkbnmhuh mmnkiurohdfb jfgnirugjhbyqrgiwqropwfo hdctrdfbcnwoyethg ub y okkjjguihrbuyrfh fjy bhjfgojwff fhgtud jujbofhf jnbiwuhfwjw nnbhh8hhy3vb yhguhjeutiu8bbb tyghiqutrbeb enibb byhuybbgerjheti4e hgietyr 12238101962 nygutythjgjoy

Thank you, Allison, for your post, and for your viewpoint! I am eager to hear more of your recommendations. Brenda

Thank you, Allison, for your post, and for your viewpoint! I am eager to hear more of your recommendations. Brenda

I enjoyed the interview with Larson. He is one of my favorite authors with an amazing ability to interweave parallel stories with historical significance. I heard him speak a couple of nights ago in St. Louis, to a full house. He is as compelling in person as on the page, and I look forward to reading "Beast." His previous books remain at the top of my "you gotta read this" list, especially "Devil in the White City" (which he says Leonardo DiCaprio has just purchased) and "Isaac's Storm."

I enjoyed the interview with Larson. He is one of my favorite authors with an amazing ability to interweave parallel stories with historical significance. I heard him speak a couple of nights ago in St. Louis, to a full house. He is as compelling in person as on the page, and I look forward to reading "Beast." His previous books remain at the top of my "you gotta read this" list, especially "Devil in the White City" (which he says Leonardo DiCaprio has just purchased) and "Isaac's Storm."

Dear Publisher,

Dear Publisher,I'd love to read this, but I hate hardcovers so I'll just have to wait for the publishers to decided that they've made enough off the hardcover version. It really annoys me that I have to wait so long in NA to read a softcover. And to add insult to injury they're often releasing digital versions before paperbacks.

Hopefully I'll remember to look for it when the paperback finally comes out.

I'm thrilled to learn Leonardo DiCaprio has bought the film rights to Devil in the White City. I pictured him as the lead in a movie of the book.

I'm thrilled to learn Leonardo DiCaprio has bought the film rights to Devil in the White City. I pictured him as the lead in a movie of the book.

Barb - Someone asked Erik Larson at the reading about the movie, if he would have some measure of control over the script or film. He said he didn't want any, that trying to have some control over a movie was useless. He quoted some famous writer - I forget which one - who said, about Hollywood: "You give them the book, you take the money, and you run." He's right. Still, I think DiCaprio has a lot of integrity and might be faithful to the book. Given the state of digital art and special effects, I bet the scenes of the Columbian Exposition will be incredible.

Barb - Someone asked Erik Larson at the reading about the movie, if he would have some measure of control over the script or film. He said he didn't want any, that trying to have some control over a movie was useless. He quoted some famous writer - I forget which one - who said, about Hollywood: "You give them the book, you take the money, and you run." He's right. Still, I think DiCaprio has a lot of integrity and might be faithful to the book. Given the state of digital art and special effects, I bet the scenes of the Columbian Exposition will be incredible.

I loved Devil in the White City, glad to hear Larson has another book out. The movie should be interesting!

I loved Devil in the White City, glad to hear Larson has another book out. The movie should be interesting!

He is a former features writer for The Wall Street Journal and Time magazine, where he is still a contributing writer. His magazine stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Harper's, and other publications. He is the author of two previous books, Lethal Passage: The Story of a Gun (1994) and The Naked Consumer: How Our Private Lives Become Public Commodities (1992).

He is a former features writer for The Wall Street Journal and Time magazine, where he is still a contributing writer. His magazine stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Harper's, and other publications. He is the author of two previous books, Lethal Passage: The Story of a Gun (1994) and The Naked Consumer: How Our Private Lives Become Public Commodities (1992).Larson grew up in Freeport, Long Island. In the years since his departure from Long Island, he has lived in Bristol, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, San Francisco (twice), Baltimore (twice), and, finally, Seattle.

I am reading "The Garden of the Beasts" and it is a very interesting book. I can hardly put it down. The Rise of Hitler and that America was not aware is so awful. Issac's Storm was fantastic also. My big project now is to go to the bookstore to get more of your books. Please continue to write, drink coffee, and eat the Oreo.

I am reading "The Garden of the Beasts" and it is a very interesting book. I can hardly put it down. The Rise of Hitler and that America was not aware is so awful. Issac's Storm was fantastic also. My big project now is to go to the bookstore to get more of your books. Please continue to write, drink coffee, and eat the Oreo.

If you're looking for a fantastic detective-fiction book, try Eobert Wilson's "A Small Death in Lisbon". Excellent.