Bionic Jean’s

Comments

(group member since Jul 27, 2022)

Bionic Jean’s

Comments

(group member since Jul 27, 2022)

Bionic Jean’s

comments

from the Works of Thomas Hardy group.

Showing 161-180 of 2,004

And a little more …

And a little more …“a day of public rejoicing was suggested to the country at large in celebration of a national event that had recently taken place”

This might have been the birth of Princess Alice (1843) or possibly Prince Alfred (1844).

The tune which Elizabeth-Jane could not resist dancing to with Farfrae “being a tune of a busy, vaulting, leaping sort—some low notes on the silver string of each fiddle, then a skipping on the small, like running up and down ladders—“Miss M’Leod of Ayr”

was one of Thomas Hardy’s favourite dance tunes.

“I’ll go to Port-Bredy Great Market to-morrow myself. You can stay and put things right in your clothes-box, and recover strength to your knees after your vagaries.” [Henchard] planted on Donald an antagonistic glare that had begun as a smile”

Port-Bredy is actually Bridport (and my closest town!) It still has a lovely traditional English market with stalls every Saturday. Which leads me to more real-life locations … Are these interesting by the way, or too remote to be meaningful, really?

Chapter 16

Chapter 16Henchard grows more reserved toward Farfrae, no longer putting his arm around the young man, or inviting him to dinner. Otherwise, their business relationship continues in a similar vein until a day of celebration of a national holiday is proposed. Farfrae has the idea to create a tent for some small celebrations, and upon hearing his idea, Henchard feels that he has been remiss, as the mayor of the town, in not organising some public festivities himself.

Henchard begins preparing for his celebrations, and everyone in the town applauds when they hear that he plans to pay for it all himself. Farfrae, on the other hand, plans to charge a small price per head for admission to his tent; an idea that Henchard scoffs at, wondering who would pay for such a thing.

Henchard’s celebrations feature a number of physical activities and games. He has greasy poles set up for climbing, a space for boxing and wrestling, and a free tea for everyone. Henchard views Farfrae’s awkward tent construction and feels confident that his own preparations are more exciting and extravagant.

The appointed day arrives, but it is overcast and gray, and starts to rain at noon. Some people attend Henchard’s event, but the storm worsens, and the tent he had set up for the tea blows over. By six o’clock though, the storm is over and Henchard hopes his celebrations will still continue. The townspeople, however, do not arrive, and Henchard learns upon questioning one man that nearly everyone is at Farfrae’s celebration.

“But Henchard continued moody and silent, and when one of the men inquired of him if some oats should be hoisted to an upper floor or not, he said shortly, ‘Ask Mr. Farfrae. He’s master here!’ Morally he was; there could be no doubt of it. Henchard, who had hitherto been the most admired man in his circle, was the most admired no longer.”

Henchard moodily closes down his celebrations and returns home. At dusk, he walks outside and follows others to Farfrae’s tent. His ingeniously constructed pavilion creates a space both for a band, and for the dance taking place. Henchard observes that Farfrae’s dancing is much admired and that he has an endless selection of dance partners. He overhears the villagers discussing himself and Farfrae, saying that he must have been a fool to plan an outdoor event on that day. Farfrae is also praised for his management, which has greatly improved Henchard’s business.

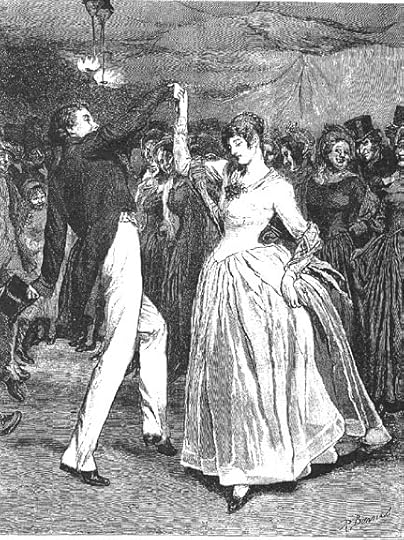

Back in the tent, Elizabeth-Jane is dancing with Farfrae.

“Farfrae was footing a quaint little dance with Elizabeth Jane” by Robert Barnes - 13th February 1886

After the dance, she looks to Henchard for fatherly approval, but instead he fixes an antagonistic glare on Farfrae. A few good-natured friends of Henchard’s tease him for having been bested by Farfrae in the creation of a town celebration. Henchard gloomily responds that Farfrae’s time as his manager is about to end, reinforcing his statement as Farfrae approaches and hears him.

“Mr. Farfrae’s time as my manager is drawing to a close--isn’t it, Farfrae?”

The young man, who could now read the lines and folds of Henchard’s strongly-traced face as if they were clear verbal inscriptions, quietly assented; and when people deplored the fact, and asked why it was, he simply replied that Mr. Henchard no longer required his help. Henchard went home, apparently satisfied. But in the morning, when his jealous temper had passed away, his heart sank within him at what he had said and done. He was the more disturbed when he found that this time Farfrae was determined to take him at his word.“

By the next morning, Henchard’s jealous temper has passed and he regrets his pronouncement that Farfrae would soon leave his employ. However, he finds that the young man is determined to do so after what Henchard said the previous evening.

Aw, thanks all! And another big thank you to Bridget, who did not hesitate to take the worry off my shoulders straightaway, when we had no idea how things with Wolfie would pan out.

Aw, thanks all! And another big thank you to Bridget, who did not hesitate to take the worry off my shoulders straightaway, when we had no idea how things with Wolfie would pan out.It's early this morning, and he's much better so far, wobbling his way into the garden (which he couldn't do last night) and generally looking more alert. He's probably going to be up and down, but the main thing now is that he wants to get better 🥰

Thanks everyone for your kind thoughts.

Thanks everyone for your kind thoughts.

We really thought we were going to lose Wolfie a few days ago. It's been a real saga, calling the emergency vets out 2 nights running. Both spent a long time with us: the second one gave myriad tests and got him stable, but it took nearly 3 hours! The next day meant transporting him to an animal hospital in London, after all the obvious causes had been eliminated. (No mean feat at any time with our car-phobic big boy, who will not allow anyone to pick him up!)

Anyway, he has two rare conditions, both of which can fortunately be treated with medication and love at home. He's not out of the woods yet, but we are much more hopeful now.

Wolfie has quite a fan club in our area; here's a card made for him by his youngest member yesterday:

Tomorrow will be a free day. We will read chapter 16 on Wednesday 9th July

Tomorrow will be a free day. We will read chapter 16 on Wednesday 9th JulyThanks all for making this such a great reading experience, despite a couple of recent blips. I'm looking forward to yet more insights 🙂

"And yet the seed that was to lift the foundation of this friendship was at that moment taking root in a chink of its structure."

"And yet the seed that was to lift the foundation of this friendship was at that moment taking root in a chink of its structure."This seems a portentous way of describing the source of Henchard and Farfrae’s falling out: a seeming trivial incident involving Abel Whittle, the perpetually tardy worker. We see that the conflict between Henchard and Farfrae arises from a different management style. Henchard scolds Abel for his tardiness, because he cares most about people following his orders. The shortness of temper we have seen before is emphasised in his interactions with Abel, as the young man tries his patience. Henchard is interested only in Abel’s performance and not his explanation of his tardiness. To us though, this might seem tyrannical.

Henchard’s treatment of Abel goes against propriety, as well as the worker’s dignity. He does not let the young man get dressed, which shames him in front of the other workers. Farfrae stands up for Abel, saying that he will leave if Abel is not treated with decency and respect, and sent home to retrieve his clothes. Farfrae uses his own weight, which is his importance to the business, to force the issue and get his own way. His way is, however, the kind and respectful treatment of any worker. Farfrae is more generous.

He believes Henchard’s behaviour is tyrannical, but Henchard does not consider the ways he could improve. Instead, he sees only a threat to his own reputation: that Farfrae challenged him, publicly, and undermined his authority as the master.

Henchard learns from a child that Farfrae is more popular than he is among the villagers. Shouldn’t this have been obvious to Henchard already, when there have been so many examples of Farfrae’s popularity? He seems to have been blinded to it by his regard for Farfrae. However, as soon as Farfrae challenges him, Henchard begins to feel threatened and to see Farfrae’s popularity as a further threat.

Henchard and Farfrae’s friendship is restored because of Farfrae’s immediate and honest apology when Henchard acts as if he has been offended. Henchard is able, at this point, to accept the apology, but he is worried, and fears Farfrae has power over him because of his knowledge of Henchard’s secret.

We seem to have another looming threat here, to add to all the secrets. I loved the nuances in this chapter, describing the psychology of personalities so well, especially Elizabeth-Jane, Henchard and Farfrae.

The “sixpence for a fairing” which Henchard uses to bribe the little boy into telling him the villagers’ opinion of him means a silver sixpence for a little cake or gift from a fair.

The “sixpence for a fairing” which Henchard uses to bribe the little boy into telling him the villagers’ opinion of him means a silver sixpence for a little cake or gift from a fair.I find this chapter interesting in structure. It starts with Elizabeth-Jane’s maturing and acceptance in the town, has a pivotal interlude in the centre, and then finishes by again examining character; this time the relationship between Farfrae and Henchard. The episode with Abel Whittle is pure Hardy: amusing but poignant too.

Elizabeth-Jane draws the attention of the villagers as she improves her fashionable appearance, as the villagers suppose her new dress to be a deliberate contrast to her old style. We see then that even at this time, fashion was the focus of interest, attention, and gossip. Some villagers misunderstand Elizabeth-Jane’s innocence and purity.

Elizabeth-Jane takes a logical view of her new popularity, realising that it is based on her appearance, and not based on her true worth: her character and her mind. She feels that those qualities are more important, which demonstrates her level-headedness, as well as her confidence that, as a woman, she is worth more than her appearance. She is, however, pleased by Farfrae’s attention.

A little more …

A little more …About the Locations in chapters 13 and 14

Susan and Elizabeth-Jane now live in a cottage “in the upper or western part of the town, near the Roman wall, and the avenue which overshadowed it.” (chapter 13)

A small portion of Roman stonework which formed part of the west wall still remains between Top o’ Town and Princes Street.

“Widow Newson” (Susan) and Michael Henchard remarry at the church after a respectable interval. The parish church for the west end of town was Holy Trinity Church, a medieval church which was rebuilt in 1824, and then again in 1875. (chapter 13)

“The corn grown on the upland side of the borough was garnered by farmers who lived in an eastern purlieu called Durnover. Here wheat-ricks overhung the old Roman street, and thrust their eaves against the church tower;” (chapter 14)

Durnover and Durnover Moor are mentioned a few times from now on. “Durnover” is a reference to Fordington, an historic area of Dorchester, Hardy knew this area well, and it partly inspired this novel, as well as a few poems. In real life, St. George’s Church, Fordington, ("Durnover") was considerably lengthened in phases between 1909 and 1928, thus destroying the Georgian chancel of 1750. The tower survived, but not the adjoining farmyard.

Chapter 15

Chapter 15Elizabeth-Jane, although she now attracts Donald Farfrae’s gaze, is still not noticed by the townspeople until her dress becomes more stylish. Henchard had bought a fine pair of gloves for her, and she bought a bonnet to match them. Then she found she had no dress to match that, and so her wardrobe grows. Some people in Casterbridge feel she has artfully created an effect by dressing plainly for so long in order to make her new appearance the more noticeable by contrast.

Elizabeth-Jane feels surprised and overwhelmed by the admiration and notice of the town, despite reminding herself that she may have gained the admiration of those types whose admiration is not worth having. But Farfrae, too, admires her. However, Elizabeth-Jane feels, after consideration, that she is admired for her appearance, which is not supported by an educated mind or a truly genteel background. She feels it would be better to sell her fine things and purchase grammar books and histories instead.

Henchard and Farfrae continue their close friendship, and yet there are hints of a disagreement. At six o’clock one evening, as the workers are leaving, Henchard calls back to a slack-jawed young man named Abel Whittle warning him not to be late again. Abel often over-sleeps and his workmates forget to wake him up. During the previous week, he had kept other workers waiting for almost an hour on two different days. Henchard will not listen to his pleas, but says he will thrash him if he is not there promptly the next morning.

The next morning at six, Abel has still not arrived at work. At six-thirty Henchard finds that the man who was to work with him that day had been waiting with his wagon for twenty minutes. Abel arrives out-of-breath just at that moment, and Henchard yells at him, swearing that if he is late the next morning that he will personally drag Abel out of bed. Abel tries to explain his situation, but Henchard will not listen.

The next morning, the wagons have to travel all the way to Blackmoor Vale, so the other workers arrive at four, but there is no sign of Abel. Henchard rushes to his house and yells at the young man to head to the granary—never mind his breeches—or that he would be fired that day. Farfrae encounters the half-dressed Abel in the yard before Henchard returns. Unimpressed with the situation, Farfrae orders Abel to return home, dress himself, and come to work like a man. Henchard arrives and exclaims over Abel leaving, and all the men look towards Farfrae. Farfrae insists that his joke has been carried far enough, and when Henchard won’t budge, he says that either Abel goes home and gets his clothes, or he, Farfrae, will leave Henchard’s employment for good.

Farfrae and Henchard privately converse, and Farfrae entreats him not to behave in this tyrannical way. Henchard is hurt that Farfrae would speak to him as he did in front of all the workers, and says it must be because he had told him his secret, but Farfrae says he had forgotten it. Henchard is moody all day, and when asked a question by a worker, exclaims bitterly: “Ask Mr. Farfrae. He’s master here!”

Thus Henchard, who was once the most admired man among his workers and in Casterbridge, is the most admired no longer. A farmer in Durnover sends for Mr. Farfrae to value a haystack, but the child delivering the message meets Henchard instead. At Henchard’s questioning, the child says that everyone always sends for Mr. Farfrae because they all like him so much. The child repeats the gossip in the town to Henchard: Farfrae is said to be better tempered then him, as well as cleverer, and that some of the women go so far as to say that they wish Farfrae were in charge rather than Henchard.

Henchard goes to value the hay in Durnover and meets Farfrae along the route. Farfrae accompanies him, singing as he walks, but he stops as they arrive remembering that the father in the family has recently died. Henchard sneers at Farfrae’s interest in protecting others’ feelings, including his own. Farfrae apologises if he has hurt Henchard in any way. Henchard decides to let Farfrae value the hay, and the pair part with their friendship renewed. However, Henchard often regrets having confessed the full secrets of his past to Farfrae, whom he now thinks of with a vague dread.

Thank you so much everyone, for your marvellous comments over the last couple of days, and especially my co-mod Bridget for taking the reins at virtually no notice! 😊I've thoroughly enjoyed reading all these new insights, often with completely new realisation about Hardy's subtlety.

Thank you so much everyone, for your marvellous comments over the last couple of days, and especially my co-mod Bridget for taking the reins at virtually no notice! 😊I've thoroughly enjoyed reading all these new insights, often with completely new realisation about Hardy's subtlety.Let's move on ...

Oh my goodness, I can't resist posting this, with an image. From the Rural Historia website, and under a spoiler to save space:

Oh my goodness, I can't resist posting this, with an image. From the Rural Historia website, and under a spoiler to save space:(view spoiler)

Apparently Mary’s fate is also part of John Cowper Powys’ novel Maiden Castle. Powys was a relative of Hardy.

Tomorrow will be our free day after every three chapters. We will read chapter 13 on Saturday 5th July.

Tomorrow will be our free day after every three chapters. We will read chapter 13 on Saturday 5th July.And please don’t miss Connie’s lead of "The Mock Wife" in our new thread yesterday. It's an unforgettable poem!

Over to you!

At the moment to me Henchard seems a man with a strong moral sense, in that he wants to do the right thing, and to do his duty, but little empathy for how others feel (e.g. Jopp). And how must Farfrae feel about this ”confession”?

At the moment to me Henchard seems a man with a strong moral sense, in that he wants to do the right thing, and to do his duty, but little empathy for how others feel (e.g. Jopp). And how must Farfrae feel about this ”confession”?His new friend and employer’s problems must be completely out of his experience, but he tries his best to advise, and willingly helps him to compose a letter. Henchard wants to send the woman in Jersey some money. To him, money seems a fitting replacement for a marriage or a relationship. Do we think the same? As Peter and others have noticed, up to a point he seems to see his wife - and now his Jersey belle - as commodities. Once again, money for Henchard is connected to the loss or gain of a human being. Feelings do not seem to come into the issue … or do they? His final thought to himself is:

“Poor thing—God knows! Now then, to make amends to Susan!”

And as Pam says, taking everything into account, what he is looking for is “the easier way for Henchard to do right by his wife and daughter.”

Michael Henchard is a complex “man of character”, for sure!

So we have a sort of interlude where we learn some of what has happened to Michael Henchard during the years after he sold his wife.

So we have a sort of interlude where we learn some of what has happened to Michael Henchard during the years after he sold his wife.To me this chapter is all about the fundamental difference between Henchard and Farfrae. Henchard succeeds through strength of personality, whereas Farfrae succeeds through hard work, diligence and attention to details as we see here with his work on the business books. Henchard compares himself with Job, but Farfrae says he never feels gloomy.

Henchard confides his story to Farfrae before he knows him very well. Although Farfrae seems likeable and trustworthy, I do have to wonder if this is wise. Will Farfrae feel obliged to keep his secret? He also reveals to Farfrae the problem with his plan of marrying Susan, yet he had not explained this to Susan in the previous chapter. We see that Henchard has a tendency to hide the truth when it benefits himself - but then so does Susan, as we see from how she represents herself as a sailor’s widow. Despite their affection and closeness in the Ring, they both hold secrets back.

Henchard’s connection with this young woman in Jersey demonstrates the power of public opinion as to a woman’s reputation at this time. Hardy expresses this ambiguously as:

“we got naturally intimate. I won’t go into particulars of what our relations were. It is enough to say that we honestly meant to marry.”

So are we are told their relationship was innocent, and that merely the affection this woman had for Henchard was enough to harm her reputation, or was it a sexual relationship, do you think? Interestingly Henchard feels that he must do what is “right” by this woman and also by Susan, without considering his actual feelings for either woman, or apparently consulting them either.

And a little more …

And a little more …“[Henchard] had in a modern sense received the education of Achilles, and found penmanship a tantalising art.”

Achilles, the hero in Homer’s The Iliad was trained in martial and practical skills, not in literary ones.

“the loneliness of my domestic life, when the world seems to have the blackness of hell, and, like Job, I could curse the day that gave me birth.”

See Job 3.3: “Let the day perish wherein I was born, and the night in which it was said, There is a man child conceived”

Chapter 12

Chapter 12Henchard returns home, and sees a light on in the office where Farfrae is still hard at work. Henchard admires Farfrae’s skill at overhauling the business’s books, as he himself is not inclined to tasks on paper, or tasks that require attention to details. Eventually, he stops the younger man’s work and insists that he join him for supper. Farfrae is already becoming used to the strength of Henchard’s requests and impulses.

Henchard wishes to tell Farfrae about a family matter, saying that he is a lonely man, and that he might as well confess all to his new friend. Henchard tells in full the story of how he sold his wife and child nineteen years ago. He says that it has not been difficult for him to remain without a wife for those many years until this very day, for his wife has come back. Farfrae asks Henchard if he cannot make amends with his wife and resume his life with her. Henchard says that is indeed what he plans to do, but, in doing so, that he must wrong another woman.

Henchard tells Farfrae of his commitment to another woman, who had nursed him one autumn when he fell ill on his trade route through Jersey. This woman fell in love with Henchard, and:

" ...being together in the same house, and her feeling warm, we got naturally intimate. I won’t go into particulars of what our relations were. It is enough to say that we honestly meant to marry."

However their proximity and the young woman's evident disregard for appearances coupled with her evident feelings for him caused a scandal in the community.

After he had come away, she wrote to him telling him how she had suffered, over many years. Henchard eventually told her that he could only marry her:

"if she would run the risk of [his wife] Susan being alive (very slight as I believed)."

She was delighted, but Henchard’s agreement to marry the woman who had cared for him was followed directly by Susan’s reappearance. Farfrae is baffled by Henchard’s complicated circumstances, which far exceed his own straightforward experiences. Henchard feels that, despite his later agreement, his first duty must be to Susan. He is sympathetic, however, toward the other woman and decides to send the poor girl some money along with a letter he asks Farfrae to help him write.

Henchard concludes his tale by telling Farfrae about his daughter and her ignorance of her own past. Despite Farfrae’s advice to tell Elizabeth-Jane the truth and ask for her forgiveness, Henchard says that he will not do so, and that he and Susan will pretend to meet and remarry before renewing their lives together.

I like this poem very much, gruesome as it is! Thanks Connie for leading this one and the useful information. Some narrative poems bore me, but this is riveting, and makes one's hair stand on end! The part about the wife's heart bursting out of her body sounds apocryphal - the sort of added ghoulish detail the Victorians loved - but it seems to have been based on fact. 😱 "a tasteless yet grim reality of 18th-century life" indeed.

I like this poem very much, gruesome as it is! Thanks Connie for leading this one and the useful information. Some narrative poems bore me, but this is riveting, and makes one's hair stand on end! The part about the wife's heart bursting out of her body sounds apocryphal - the sort of added ghoulish detail the Victorians loved - but it seems to have been based on fact. 😱 "a tasteless yet grim reality of 18th-century life" indeed.This takes me back to the first chapter, where Michael Henchard as a young man was reading a ballad sheet. Perhaps this horrifying story - or one very like it, was included among the local news and songs he was so absorbed in.

Here's more on Maumbury Rings https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maumbur...

I find it oddly interesting that the real life site is plural. Perhaps Thomas Hardy removed the "s" and called it "The Ring" so that he could make more symbolic use of it.

(All the links are now in place.)

Peter wrote: "their relationship has come full circle ..."

Peter wrote: "their relationship has come full circle ..."What a perfect metaphor for our "ring" motif Peter! 😄 Plus we have Claudia's "skeletons in the cupboard" too, to relate to the Roman remains. I love it!

Connie wrote: "Jean, I led the poem "The Roman Road"... [and] Donald led "Roman Gravemound" "

Connie wrote: "Jean, I led the poem "The Roman Road"... [and] Donald led "Roman Gravemound" "Thank you for jogging my memory Connie! If I had only been able to remember the titles, I could have used our list of poem threads 🙄 😆

I love your point about the bird imagery too ... people are finding so many instances of this in The Mayor of Casterbridge, which I'd never noticed before! 😊